From the archives of political satire

these works preserve a tradition of dissent—

continuing its vigilance in the present.

Mugs

Mugs

Filters

Satire of political access and the transactional culture of patronage.

The image frames public office as something allocated through negotiation rather than merit. Ambition waits in line, legitimacy is contingent, and power circulates through proximity and influence instead of qualification. Governance appears less representative than brokered, exposing how access itself becomes currency.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1883 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. It critiques the American patronage system of the late nineteenth century, portraying congressional seats as commodities shaped by political machines and media influence.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical treatment of political performance and empty display.

When ambition is staged through slogans and props rather than ideas and responsibility, spectacle begins to substitute for substance. That dynamic was already visible in the late nineteenth century—and it has never entirely disappeared.

Historical note:

The Don Quixote-sque cover image comes from an 1884 issue of Puck magazine, illustrated by Bernhard Gillam, a leading Gilded Age political cartoonist known for satirizing corruption, ambition, and political spectacle.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at elite corruption and the ceremonial division of public wealth.

The image presents governance as courtly theater, where authority gathers not to serve but to claim its portion of excess. Power appears ornamental and acquisitive, exposing a political class more invested in managing spoils than representing citizens.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1884 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. It depicts politicians as Renaissance courtiers competing over a heap labeled “surplus,” critiquing over-taxation, mismanagement, and the pageantry of elite corruption. The version reproduced here comes from a German-language edition of Puck, which retained the original English captions within the artwork.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire directed at speculative excess and institutional denial.

When markets reward recklessness and those responsible insist on their own innocence, cycles of crisis and erasure repeat themselves. Late-nineteenth-century satire recognized this pattern with clarity—and it has not lost its relevance.

Historical Note

This image appeared in an 1884 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Joseph Keppler. It depicts a “Wall Street cleaner” sweeping gamblers, stock-jobbers, and speculative schemes through the financial district, reflecting contemporary criticism of unchecked speculation and market fraud during the Gilded Age.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at elite corruption and the ceremonial division of public wealth.

The image presents governance as courtly theater, where authority gathers not to serve but to claim its portion of excess. Power appears ornamental and acquisitive, exposing a political class more invested in managing spoils than representing citizens.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1884 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. It depicts politicians as Renaissance courtiers competing over a heap labeled “surplus,” critiquing over-taxation, mismanagement, and the pageantry of elite corruption. The version reproduced here comes from a German-language edition of Puck, which retained the original English captions within the artwork.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satire of political demagoguery and the attempted capture of the press.

The image frames influence as performance rather than persuasion, exposing how power tries—and fails—to convert spectacle into obedience. Authority appears confident in its charm, yet unable to command credibility, underscoring the role of resistance in public discourse.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1884 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Frederick Burr Opper. It depicts a political figure modeled on the Pied Piper attempting to lure newspaper editors with a flute labeled “Magnetic Influence,” satirizing efforts to manipulate the press during the Republican National Convention.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satire of political demagoguery and the attempted capture of the press.

The image frames influence as performance rather than persuasion, exposing how power tries—and fails—to convert spectacle into obedience. Authority appears confident in its charm, yet unable to command credibility, underscoring the role of resistance in public discourse.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1884 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Frederick Burr Opper. It depicts a political figure modeled on the Pied Piper attempting to lure newspaper editors with a flute labeled “Magnetic Influence,” satirizing efforts to manipulate the press during the Republican National Convention.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

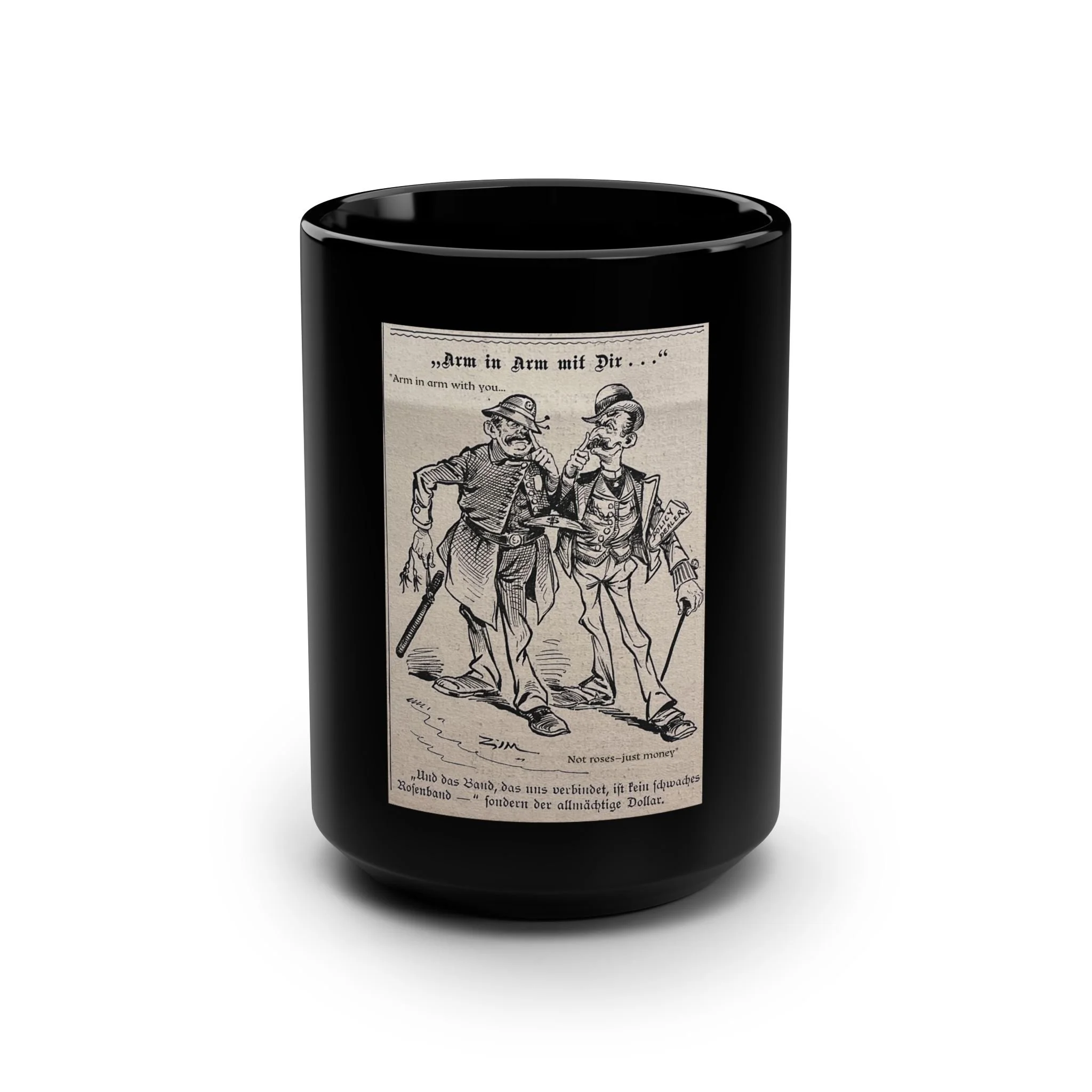

Satire aimed at corruption, collusion, and the quiet normalization of abuse of power.

The image presents authority and vice as companions rather than opposites, bound together by shared interest rather than obligation. Accountability recedes as profit takes the lead, suggesting how public trust erodes when enforcement aligns with exploitation.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1884 issue of Puck magazine. It depicts a police officer walking arm in arm with a policy dealer, using irony to critique the relationship between law enforcement and illicit commerce during the Gilded Age.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical critique of political patronage and the exhaustion of governance under constant demand.

The image depicts public office as an endless burden rather than a position of service, where obligation multiplies and authority is measured by what can be distributed rather than what can be governed. Power appears transactional and unsustainable, suggesting a system in which pressure and loyalty eclipse responsibility.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in Judge magazine during the late nineteenth century and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. It satirizes the Republican spoils system of the Gilded Age, portraying the strain of patronage politics and the corrosive effects of party bosses exerting control over public office.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical critique of civic rivalry and the transformation of public ambition into spectacle.

The image presents political decision-making as staged anticipation, where cities compete for recognition through display rather than deliberation. Pride and lobbying blur into performance, suggesting that the pursuit of prestige often amplifies noise while obscuring substance.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1889 issue of Judge magazine. It satirizes the contest among American cities to host the 1893 World’s Fair, using theatrical framing to highlight how civic ambition and political maneuvering slid easily into spectacle.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A study in political failure and the refusal to let go of discredited power.

The image frames authority as a burden that drags everything around it downward. Rather than confront collapse, allies strain to recover what cannot be salvaged, exposing how loyalty to failed leadership turns maintenance into farce and accountability into avoidance.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1889 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam. It features the recurring figure “McGinty,” a satirical stand-in for the scandal-ridden party boss, shown stranded amid wreckage while operatives attempt to pull him back—critiquing machine politics and the protection of incompetence.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

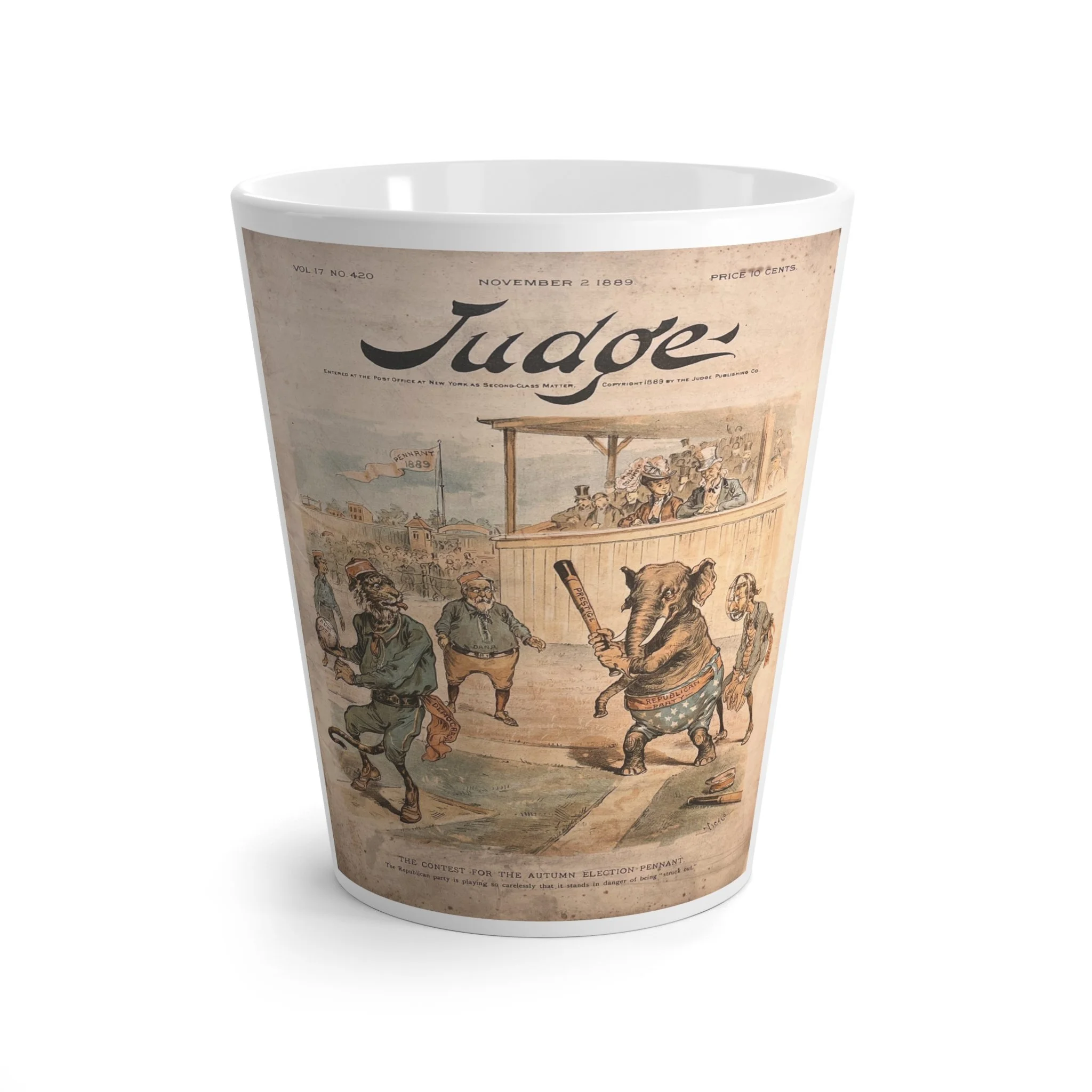

Satire focused on political complacency and the consequences of careless power.

The image frames electoral politics as a competitive arena where GOP misjudgment and overconfidence invite defeat. Authority appears inattentive and exposed, suggesting that dominance erodes when discipline gives way to entitlement and routine advantage.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1889 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam, a prominent political cartoonist of the Gilded Age known for his critiques of party politics, corruption, and electoral strategy.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

An examination of imperial arrogance and the fantasy of benevolent control.

The image presents foreign policy as self-appointed stewardship, where influence is asserted as guidance and domination is framed as help. Power assumes entitlement to direct others’ futures, exposing how confidence in one’s own virtue can slide easily into coercion.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1889 issue of Judge magazine. It satirizes James G. Blaine’s vision of U.S. economic and political leadership over Latin America, critiquing the paternalism and manufactured consent embedded in late-nineteenth-century imperial ambition.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical treatment of electoral reform and the fear it provokes among entrenched power.

The image frames democracy as something actively resisted by those who benefit from its distortion. Reform pulls forward while corruption clings behind, exposing how threats to rigged systems trigger panic rather than adaptation. The message is structural rather than partisan: fair rules are dangerous to those who depend on unfair advantage.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1890s issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Grant E. Hamilton. It satirizes political machines’ resistance to ballot reform, portraying corruption struggling to hold on as fair elections move beyond its reach.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at denial, unpreparedness, and the costs of treating crisis as inconvenience.

The image frames national illness as an uninvited guest met with bravado rather than readiness. Remedies clutter the scene without effect, suggesting how confidence and improvisation replace planning when reality intrudes. Responsibility arrives late, after damage is already done.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1890 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Grant E. Hamilton. It personifies the influenza epidemic as a visiting figure confronting an unprepared Uncle Sam, critiquing public complacency and ineffective responses to widespread illness.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

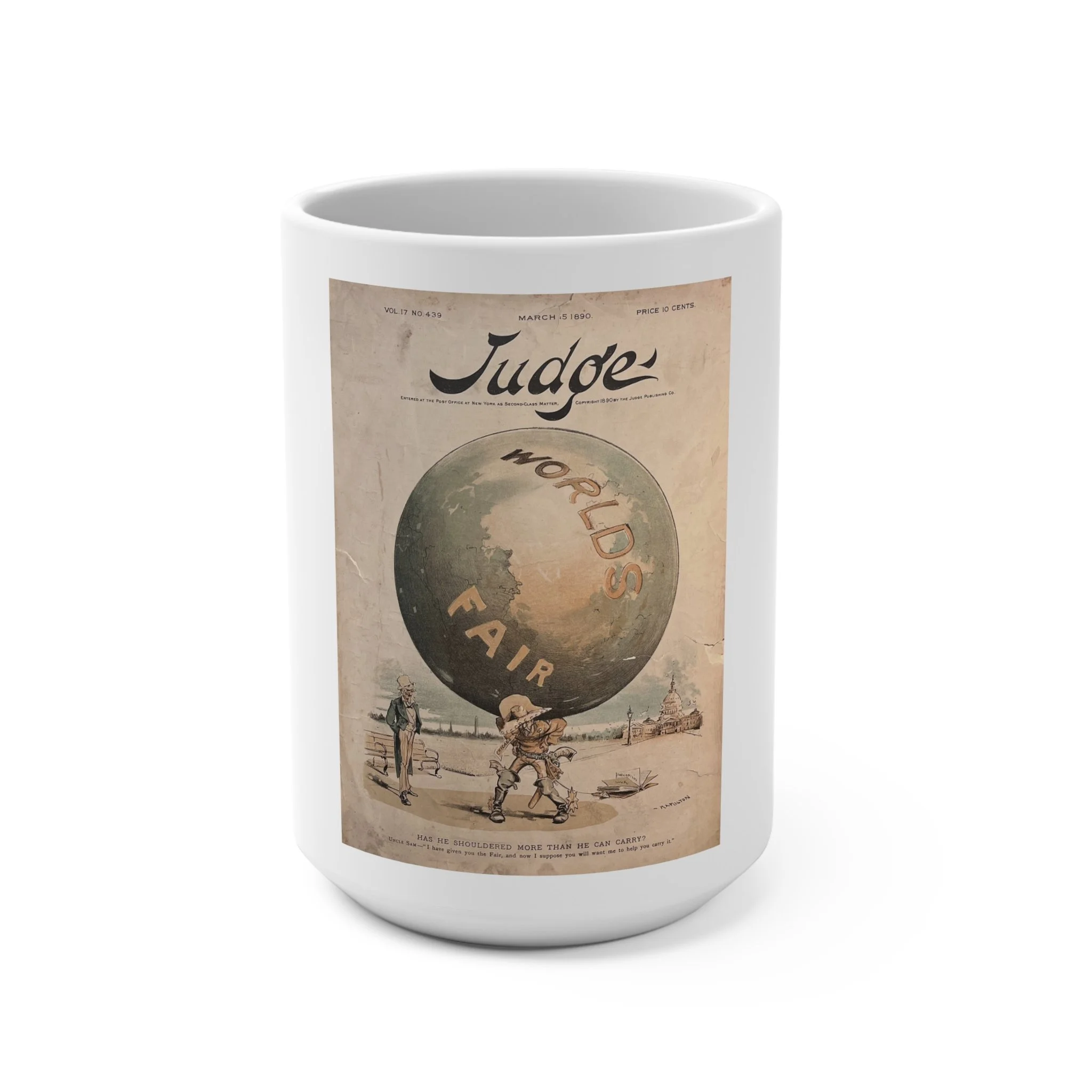

Satire directed at civic ambition inflated beyond capacity.

When leaders pursue prestige, spectacle, and headlines as ends in themselves, public institutions are often left to absorb the weight. Late-nineteenth-century satire recognized how grand projects can substitute image for governance—and how the consequences are rarely carried by those who make the promises.

Historical note:

The image comes from an 1890 issue of Judge magazine, critiquing Chicago’s campaign to host the World’s Columbian Exposition. The cartoon depicts the city personified as an overconfident figure straining beneath a globe labeled “World’s Fair,” while Uncle Sam looks on skeptically.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical critique of political mythology and the way power narrates itself as inevitability.

The image frames domination as forward motion, where opposition is dismissed as obstruction and authority claims moral certainty through sheer momentum. What appears as progress is revealed as force, suggesting how concentrated power recasts coercion as historical necessity.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1890 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. It portrays the Republican Party as an unstoppable engine of “progress,” satirizing how political movements frame momentum as moral certainty while flattening dissent.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A study in institutional decay and the collapse of accountability behind claims of order.

The image presents corruption not as hidden failure but as visible accumulation, where bribery and selective enforcement pile up beyond denial. Authority appears reactive and evasive, exposing how appeals to “law and order” often mask systems that protect power rather than justice.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1890 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam. It satirizes corruption within New York’s police and prosecutorial institutions, depicting political figures scrambling to avoid scrutiny as investigative pressure mounts.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

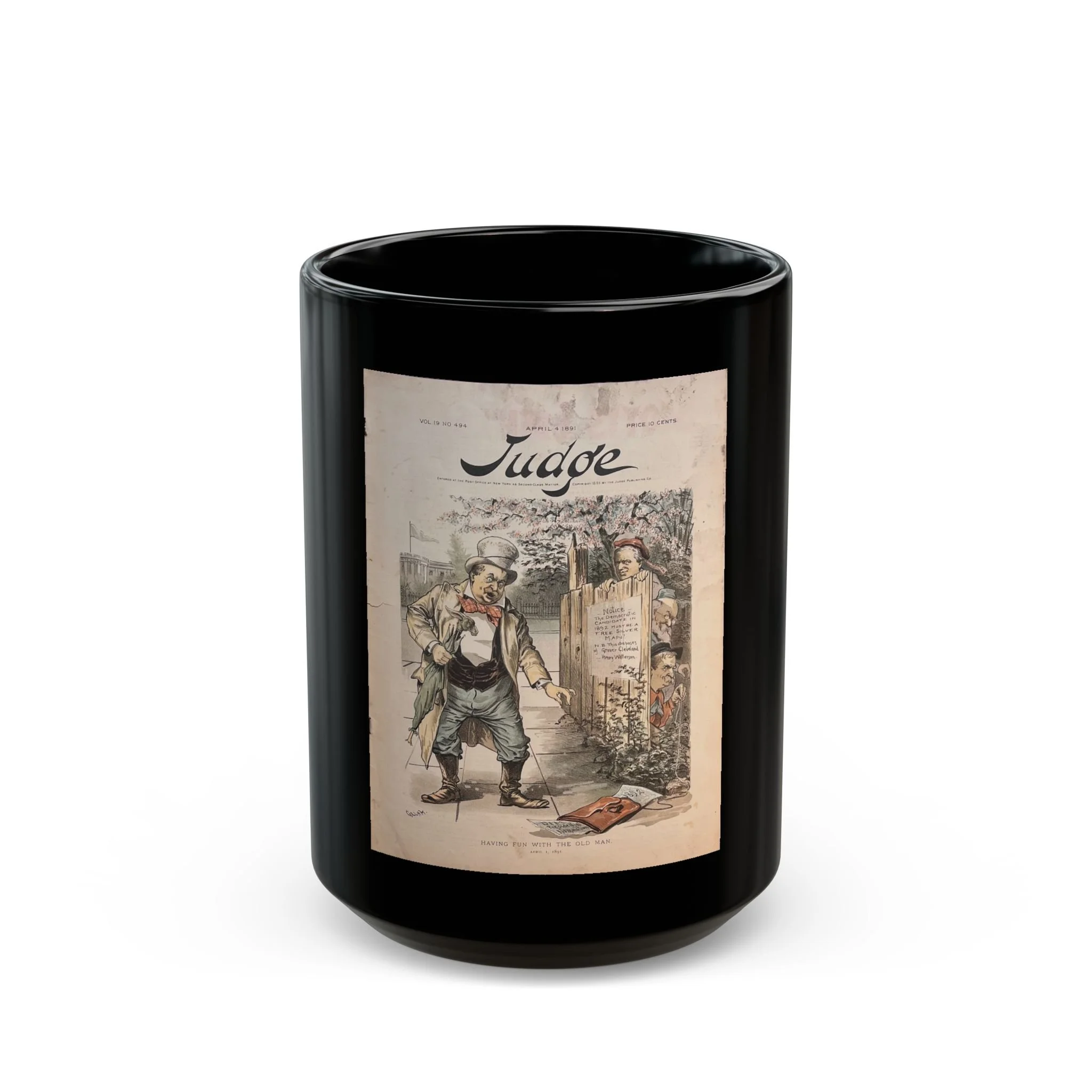

A study in factional leverage and the mechanics of internal political pressure.

The image focuses less on policy than on persistence—how authority is tested through nudging, repetition, and coordinated demand. Power appears constrained not by opposition from outside, but by maneuvering within, exposing how parties reshape themselves through pressure rather than persuasion.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an April 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. It depicts Democratic Party factions pressuring Grover Cleveland during debates over Free Silver, reflecting skepticism toward internal gamesmanship and efforts to force political realignment ahead of the 1892 election.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A depiction of opportunism, coalition panic, and the instinct to flee accountability.

The image frames politics as a collective rush for safety, where rivals abandon principle in favor of proximity to power. Unity emerges not from conviction but from fear, exposing how coalitions rearrange themselves when public mood turns and consequences approach.

Historical Note

This satirical spread appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. Using the allegory of Noah’s Ark, it portrays America’s major political factions as anxious animals crowding toward the Farmers’ Alliance, critiquing opportunism during a period of corruption and economic upheaval.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical critique of institutional congestion and the paralysis of inward-facing power.

The image presents governance as a struggle over space rather than responsibility, where ambition crowds out function and process substitutes for outcome. Authority collapses under its own weight, exposing how institutions become obstacles when consumed by factional competition instead of public purpose.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was drawn by Grant E. Hamilton. It reduces the U.S. Senate to a single overcrowded chair, satirizing legislative dysfunction and the way internal struggles can bring democratic institutions to a standstill.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

An examination of engineered failure and the mechanics of corrupt advantage.

The image presents competition as illusion, where outcomes are controlled long before participation begins. Authority appears complicit at every level, exposing how systems advertised as fair are structured to reward insiders while insulating them from consequence.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in an 1890s issue of Judge magazine and was drawn by Grant E. Hamilton. It satirizes rigged gambling rackets and the political corruption that sustained them, depicting bettors misled by spectacle while officials and operators manipulate the results.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

An examination of engineered failure and the mechanics of corrupt advantage.

The image presents competition as illusion, where outcomes are controlled long before participation begins. Authority appears complicit at every level, exposing how systems advertised as fair are structured to reward insiders while insulating them from consequence.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in an 1890s issue of Judge magazine and was drawn by Grant E. Hamilton. It satirizes rigged gambling rackets and the political corruption that sustained them, depicting bettors misled by spectacle while officials and operators manipulate the results.

A satirical critique of political appropriation and manufactured success.

The image presents public ambition as a performance built on display rather than achievement. Authority is shown claiming outcomes it did not earn, relying on spectacle and repetition to convert loss into the appearance of victory. Power, here, is less about results than about who controls the narrative.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam. It uses visual parody to critique political figures who claim credit through exaggeration, display, and rhetorical sleight of hand rather than electoral fact.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical treatment of policy failure defended as political success.

The image frames governance as self-congratulation in the face of damage, where harm is acknowledged but left untouched because correction carries risk. Authority praises endurance instead of responsibility, exposing how cowardice becomes policy when change threatens those in power.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine. It critiques political leaders who defended a damaging tariff law not for its results, but because reversing it was deemed too dangerous, capturing a moment of Gilded Age self-justification and institutional inertia.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

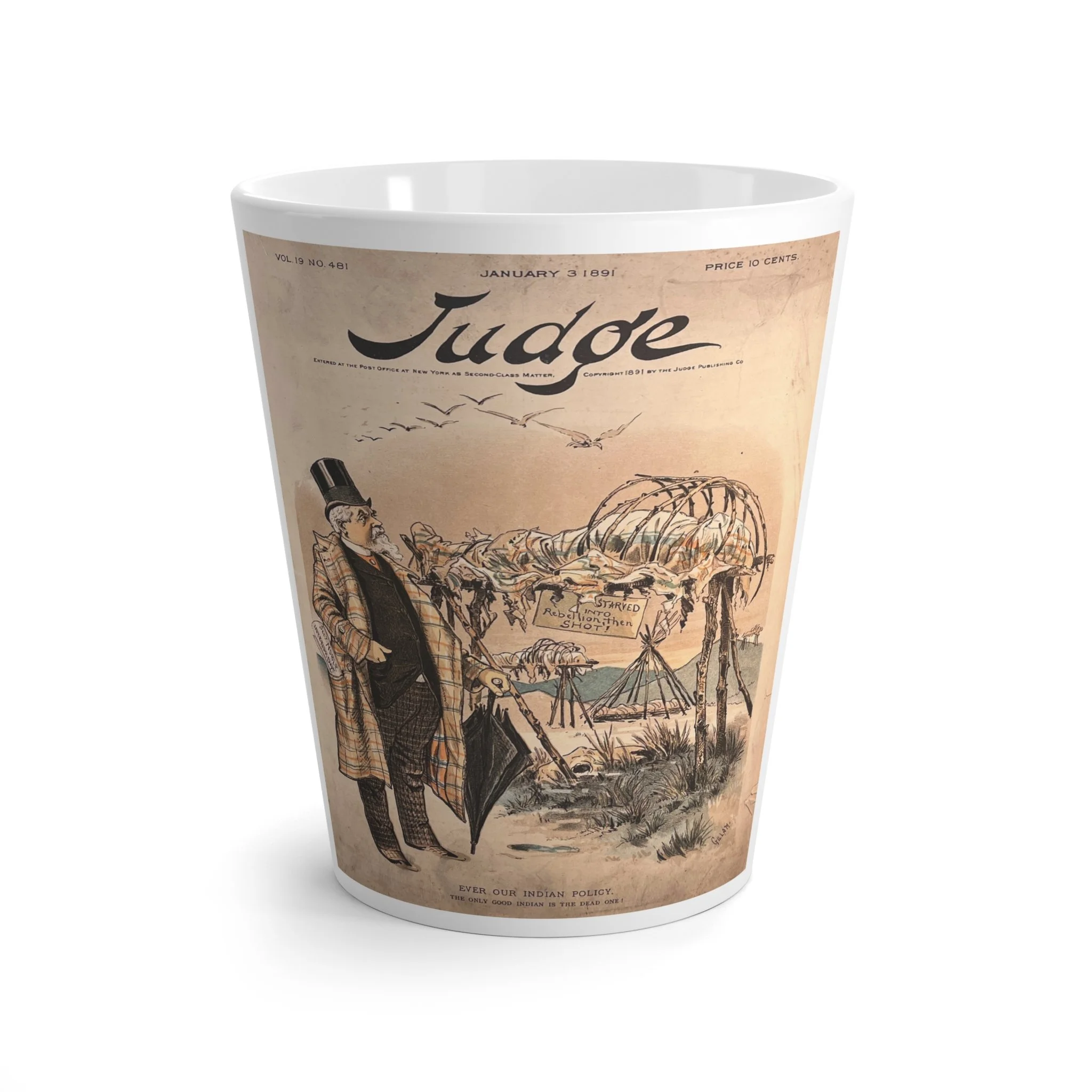

An examination of state violence, manufactured justification, and the moral logic of colonial power.

The image exposes a cycle in which deprivation is engineered, resistance is provoked, and brutality is then framed as necessity. Authority appears self-satisfied and untroubled, revealing how policy disguises violence through distance, rhetoric, and bureaucratic calm.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. Published just days after the Wounded Knee Massacre, it indicts U.S. Indian policy by depicting a senator passing a skeletal encampment labeled “Starved into rebellion, then shot,” targeting the policymakers responsible for starvation, displacement, and lethal retaliation.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A depiction of exclusion, entitlement, and the limits of access.

The image frames public authority as something withheld rather than granted, where expectation collides with refusal. Privilege is shown lining up out of habit, only to be turned away—suggesting that legitimacy depends on restraint as much as admission.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam. It satirizes political insiders who assumed automatic access to power, using the closed gate as a metaphor for democratic boundaries.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical treatment of repetition, obedience, and the exhaustion of empty leadership.

The image frames authority as insistence rather than persuasion, where the same message is demanded long after it has lost its audience. Public patience gives way to refusal, exposing how propaganda loops collapse when performance replaces results.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine. It depicts a military-style band refusing to continue playing for an enraged commander, using humor to critique political movements that rely on repetition and loyalty instead of adaptation and accountability.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at electoral reform and the dismantling of corrupt political power.

The image reframes democratic protection as deliberate action, where strength is stripped not through force but through rules, registration, and transparent voting. Authority weakens as secrecy and manipulation are removed, revealing how organized reform cuts through systems built on intimidation and control.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine. Recasting the biblical story of Samson and Delilah, it depicts Columbia severing the “strength” of a political boss with tools labeled Ballot Reform, Registration, and The Australian Ballot, satirizing machine politics and the fight for fair elections.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire depicting performative unity and the spectacle of incompatible alliance.

The image presents agreement as something staged rather than achieved, where moral opposites are placed side by side and declared harmonious by fiat. Cooperation appears theatrical and unstable, suggesting that proclaimed unity can mask deeper incoherence rather than resolve it.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. Titled “The Duet of the Saint and the Sinner,” it uses visual contrast to critique political alliances that announce harmony while exposing fundamental contradiction.

A study in empty rhetoric and the distance between political language and lived reality.

The image frames reform as accumulation rather than action, where speeches and promises pile up while conditions remain unchanged. Authority appears verbose but inert, revealing how the language of improvement can be used to stall accountability and exhaust public patience.

Historical Note

This illustration by Bernhard Gillam appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine. It depicts weary farmers standing amid discarded “reform” speeches and policy scrolls, satirizing politicians who invoke reform while avoiding substantive change and exposing the hollowness of performative politics.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A depiction of surrender framed as pragmatism and cowardice disguised as loyalty.

The image casts political retreat as moral failure, where claims of unity mask capitulation and resolve gives way to convenience. Authority abandons principle in the name of peace, revealing how appeasement feeds the very forces it claims to restrain.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1890s issue of Judge magazine. Titled Unconditional Surrender, it uses Civil War imagery to satirize politicians who profess allegiance while enabling anti-democratic forces, warning that capitulation is not compromise but complicity.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire directed at civic ego and manufactured inevitability.

Whenever politicians treat public institutions as tools to boost their own image—or when local power brokers insist that their interests are everyone’s interests—this kind of satire becomes timeless.

Historical note:

The image comes from an 1891 issue of Judge magazine, satirizing Chicago’s campaign to secure the World’s Columbian Exposition. The cartoon portrays the “average Chicago man” overwhelmed by booster slogans and political pressure.

A study of mass participation, public performance, and the instability of collective enthusiasm.

The image presents civic life as a crowded stage, where ambition, humor, and tension coexist without clear hierarchy. Public energy appears expansive and animated, yet precarious—suggesting that national identity is formed as much through spectacle and proximity as through order or consensus.

Historical Note

This two-page illustration appeared in an early 1890s issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Joseph Keppler. Known for large ensemble scenes, Keppler used dense composition to explore the performance of power, social diversity, and the contradictions of American public life.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at electoral corruption and the open purchase of political power.

The image presents democracy as something treated like a transaction, where loyalty is bought, secrecy is assumed, and force stands ready as backup. Authority appears confident in its impunity, exposing how insiders normalize fraud when winning matters more than legitimacy.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1892 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Louis M. Dalrymple. It reproduces language from an actual political circular, depicting a party operative openly distributing bribe money to secure votes, and reflects Puck’s sustained critique of fraud, bribery, and authoritarian tactics disguised as moral politics.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

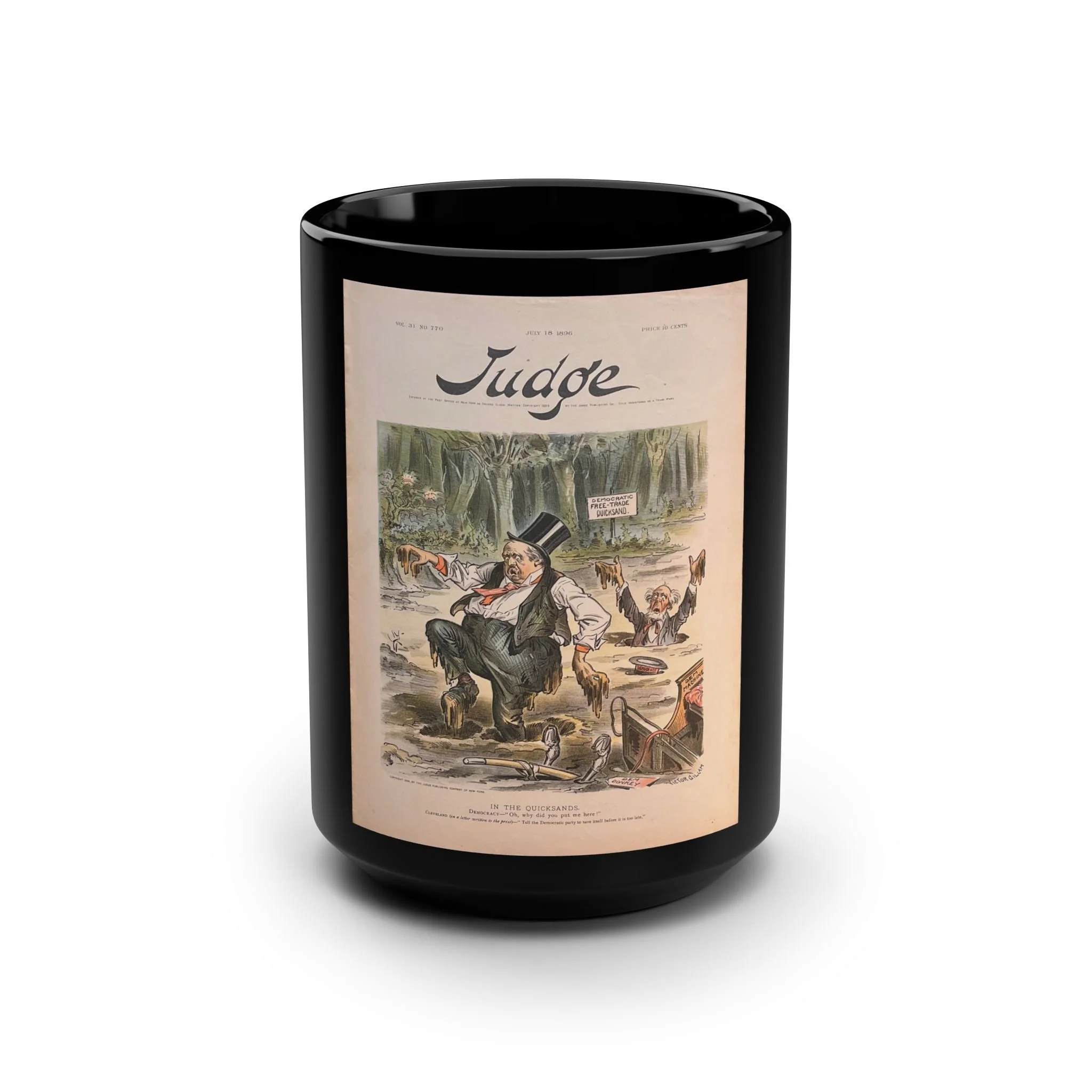

Satire aimed at party orthodoxy and the self-inflicted collapse of political authority.

The image turns ideology into terrain, depicting a party platform as literal quicksand that pulls its own leaders downward. Power does not fall to opponents here—it sinks under the weight of its own certainty. Broken emblems in the mud underscore the message: machine politics and institutional strength become liabilities when policy hardens into dogma.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1896 issue of Judge. Illustrated by Victor Gillam, it critiques President Grover Cleveland and the Democratic Party’s free-trade platform during the turbulent 1896 election debates over tariffs and economic policy.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

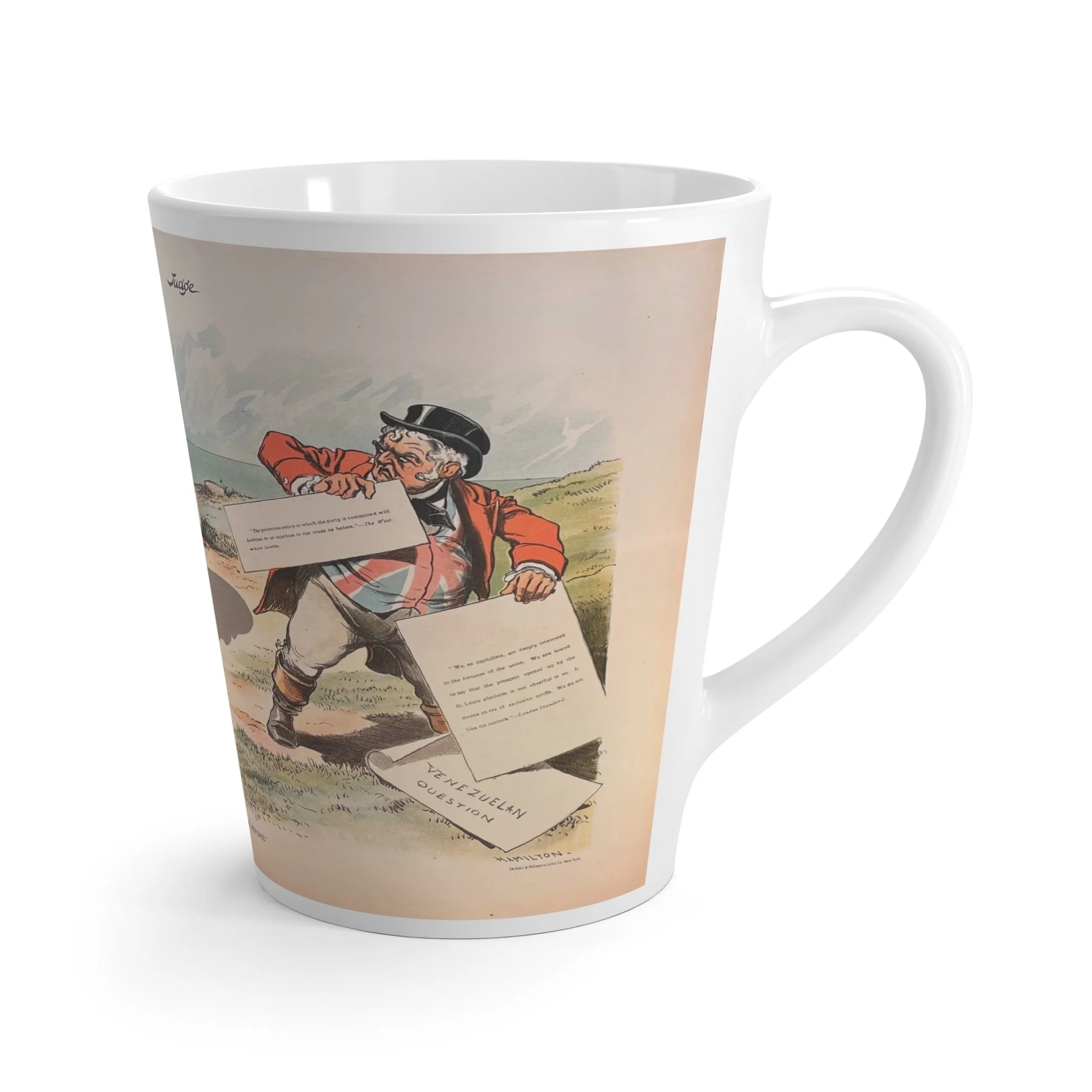

A satirical critique of expansionist ambition and the use of language as a substitute for restraint.

The image portrays power advancing through declarations rather than force, suggesting that imperial consequences often take shape before conflict formally begins. Authority appears confident in speech while shadowed by outcomes already set in motion, exposing the gap between proclamation and responsibility.

Historical Note

This large-format cartoon appeared in a July 1896 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Grant E. Hamilton. Responding to the Venezuelan Question, it reflects late-nineteenth-century American satire skeptical of imperial rhetoric and the justifications used to normalize expansion.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical critique of how care and endurance operate within systems of mass violence.

The image shifts attention away from combat to the quieter labor that sustains life amid destruction. Care appears as presence rather than spectacle, emphasizing steadiness, reassurance, and routine as forms of resistance within the machinery of war.

Historical Note

This spread appeared in a 1915 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Fabien Fabiano. Organized around a red cross motif, it depicts everyday moments of wartime nursing, highlighting medical care as both labor and refuge in First World War hospitals.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

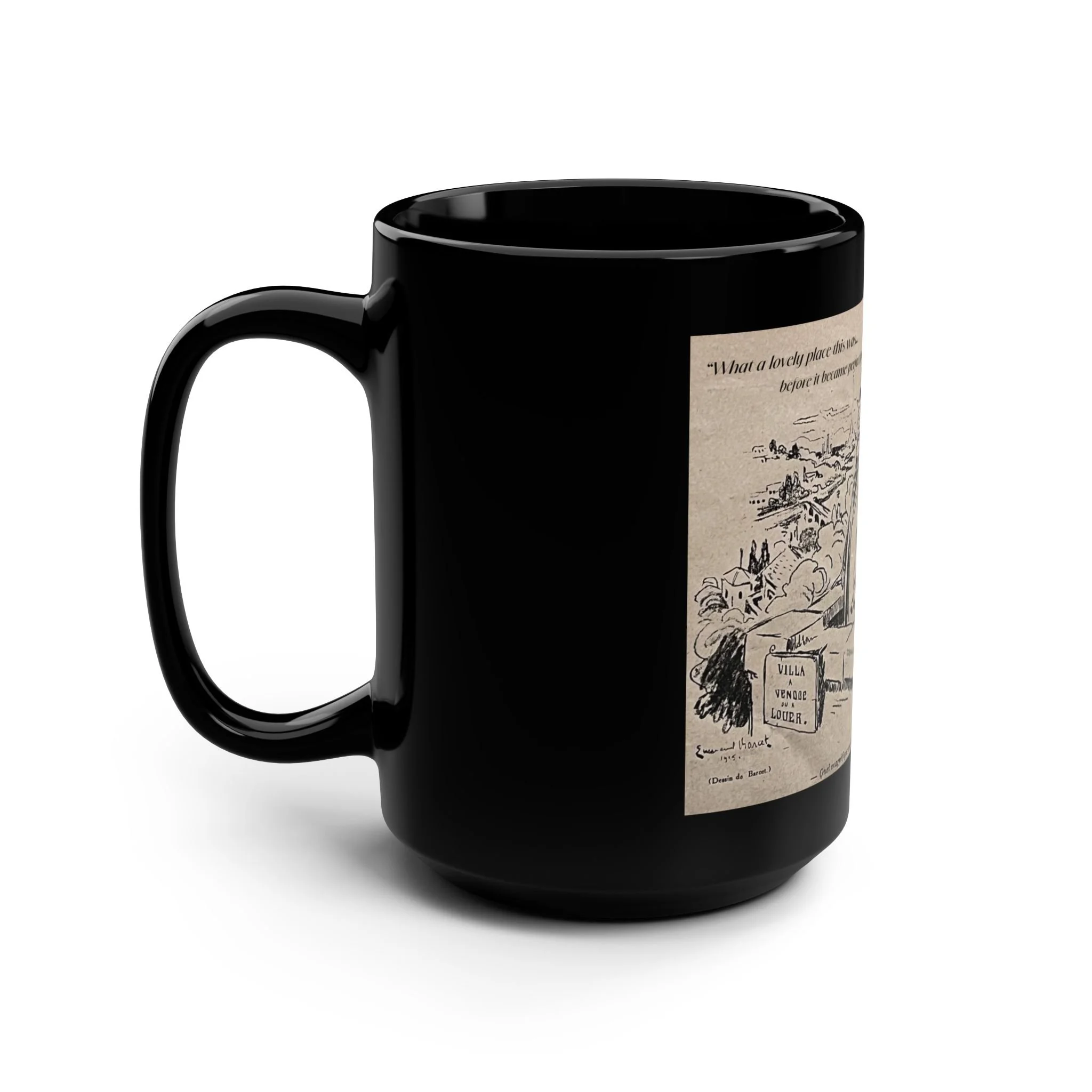

A study in fear, projection, and the civilian imagination under militarization.

The image presents anxiety as a way of seeing, where ordinary landscapes are reinterpreted as latent threats. Suspicion becomes conversational and self-reinforcing, showing how war teaches civilians to narrate danger into existence long before violence arrives.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in a 1915 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Emmanuel Barcet. It satirizes the spread of wartime paranoia, depicting how military logic reshapes civilian perception during the First World War.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at militarism, exhaustion, and the collapse of imperial myth.

The image reduces a symbol of dominance to a figure of strain and injury, stripping authority of spectacle and inevitability. Power appears grounded and diminished, confronting the limits of force once grandeur gives way to consequence.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared during the First World War in La Baïonnette and was drawn by Adolphe Willette. Using the German imperial eagle as a stand-in for militarism, it reflects French wartime satire’s unsentimental critique of authoritarian power.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical treatment of imperial power consumed by its own violence.

The image frames authority as something that endures structurally while eroding morally. Rank, uniform, and command remain intact, but the figure at the center appears hollowed and depleted, suggesting that militarism corrodes those who wield it as surely as those subjected to it.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an October 1916 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Gus Bofa. Depicting Kaiser Wilhelm II before and after the toll of war, it reflects French wartime satire that treated empire as self-corrosive rather than heroic.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at the redefinition of loyalty under conditions of total war.

The image presents transformation as quiet and unquestioned, where familiar roles are repurposed for national ends. What once belonged to private life is recast as public obligation, suggesting how war absorbs everyday symbols and redirects them toward collective duty.

Historical Note

This page appeared in a 1916 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Jacques Nam. Using a simple two-panel allegory, it reflects how wartime ideology reframed personal loyalty as a resource of the nation.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire directed at figures who profit, posture, and presume themselves untouchable.

When political authority, financial advantage, and moral certainty converge in the same hands, caricature becomes a form of record-keeping. Wartime satire captured these faces with precision—and the type has not disappeared.

Historical note:

The image comes from a 1916 issue of the French satirical magazine La Baïonnette. The caricature page presents a gallery of so-called “undesirables,” targeting politicians, profiteers, and public figures associated with corruption and wartime exploitation. The original caption reads: « Quelques têtes d’indésirables » (“Some undesirable faces”).

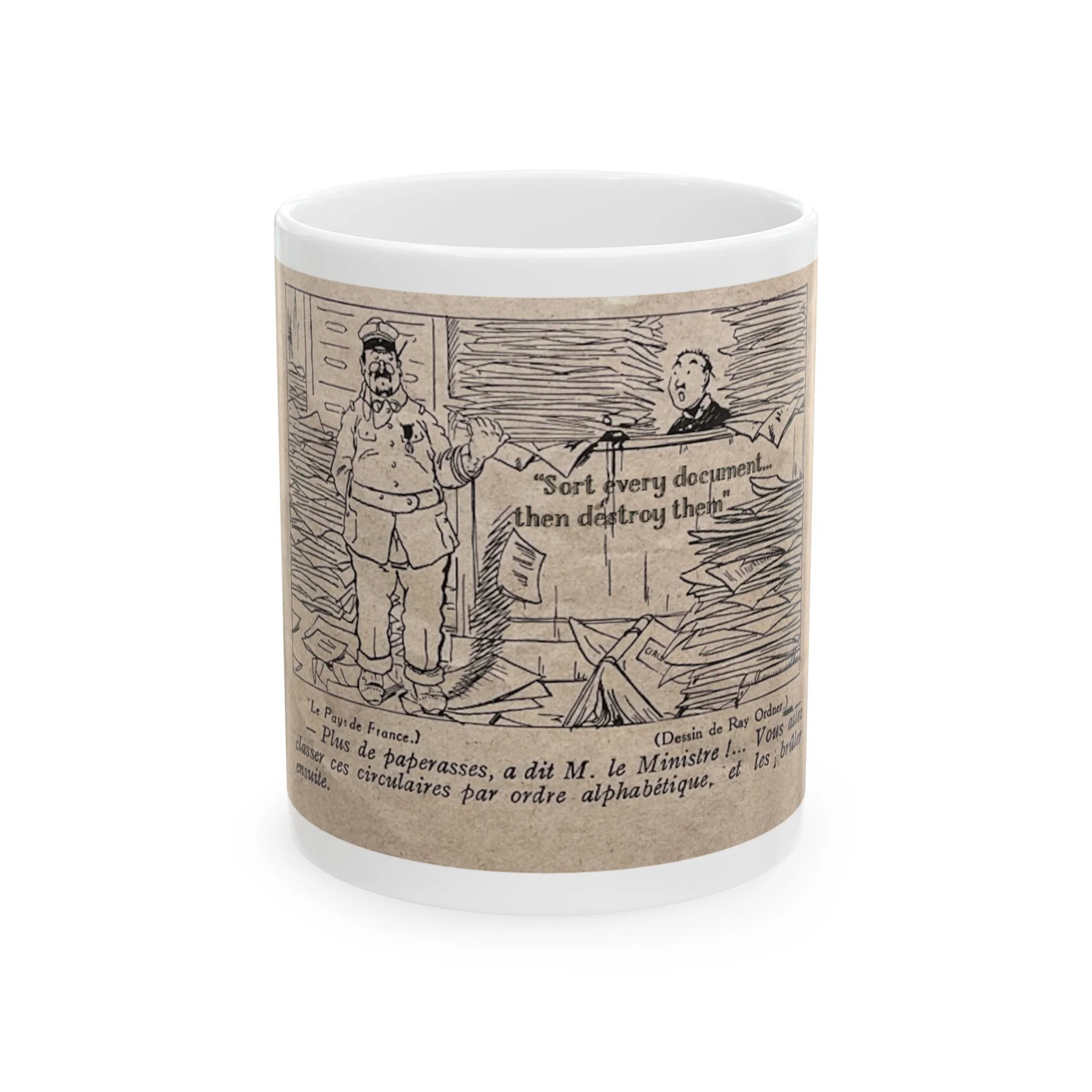

An examination of process as power and paperwork as a substitute for responsibility.

The image presents authority turned inward, where procedure replaces purpose and documentation stands in for results. Control is exercised not through effectiveness, but through repetition, compliance, and the quiet intimidation of endless administrative motion.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in a 1916 issue of La Baïonnette and was drawn by Opnor. It satirizes authoritarian bureaucracy by depicting power absorbed in paperwork rather than problem-solving, critiquing systems that protect themselves through procedure instead of public service.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A dry satire of bureaucratic confidence under strain.

When institutions insist on their own stability while human consequences recede into the background, irony becomes unavoidable. Wartime satire recognized this tension clearly—and the pattern remains familiar.

Historical note:

The image comes from a 1916 issue of the French satirical magazine La Baïonnette. The cartoon depicts Monsieur Lebureau, buried in documents, insisting that bureaucracy will endure.

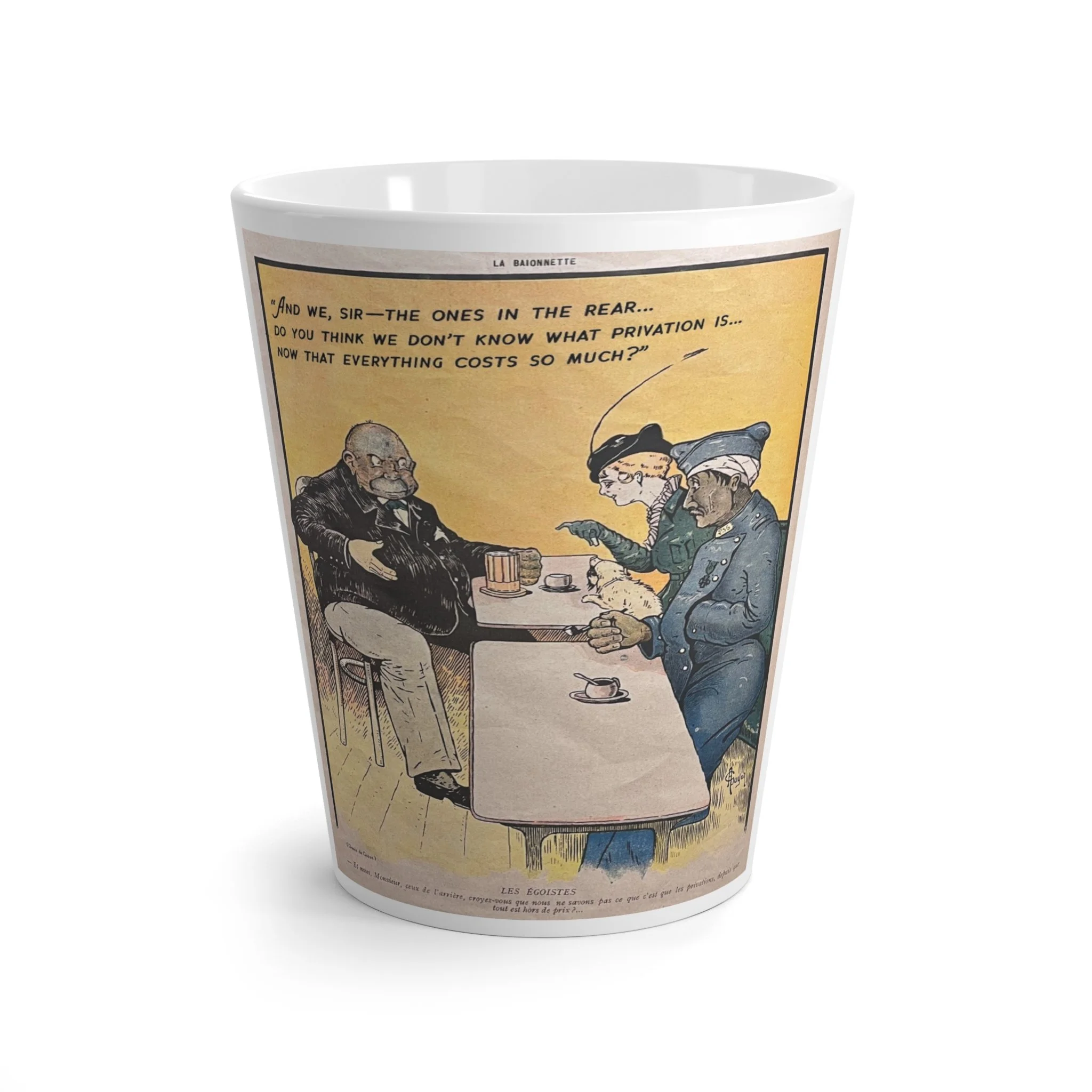

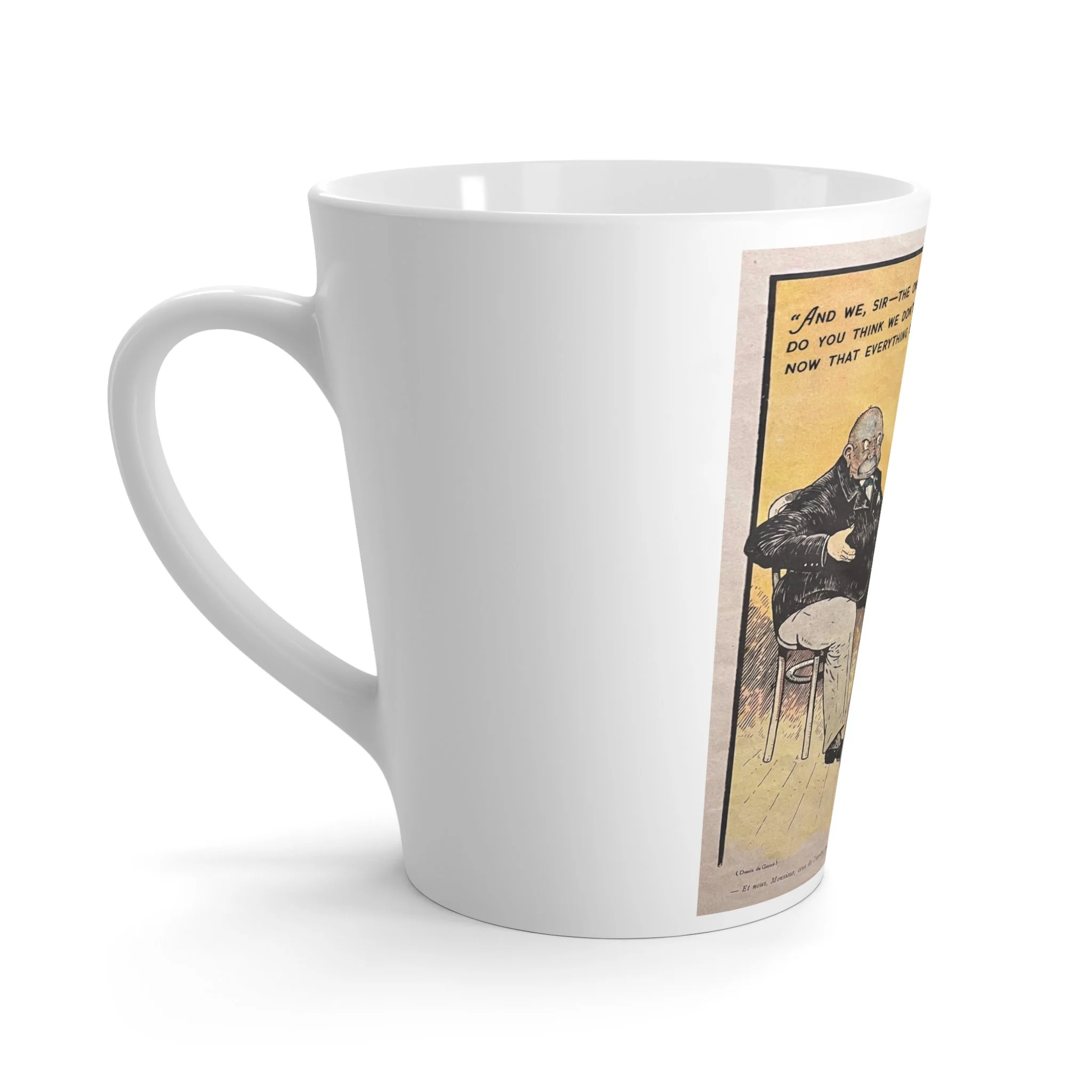

A satirical critique of privilege, complaint, and the appropriation of suffering.

The image contrasts lived injury with comfortable grievance, exposing how those shielded from consequence adopt the language of hardship without bearing its cost. Sacrifice is discussed abstractly while its realities sit plainly ignored, making inequality visible through proximity rather than argument.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in a 1916 issue of La Baïonnette. It juxtaposes a wounded frontline soldier with a rear-guard bourgeois lamenting rising prices, using irony to critique how privilege reframes inconvenience as sacrifice during wartime.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A study in popular resistance and the refusal to negotiate with authoritarian power.

The image presents expulsion rather than persuasion as the only response to tyranny. Authority is not corrected or reasoned with, but physically removed, underscoring the idea that entrenched power rarely relinquishes control without forceful opposition.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared during the First World War in La Baïonnette and was drawn by A. Willette. Titled “À la porte les tyrans” (“Out with the tyrants”), it channels public anger into a direct visual command, reflecting wartime French satire’s blunt rejection of authoritarian rule.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A depiction of procedural performance and the illusion of governance through routine.

The image presents authority as ritualized motion, where gestures repeat and deliberation substitutes for consequence. Continuity is performed as virtue, exposing how power maintains itself by extending process while deferring responsibility.

Historical Note

This illustration was published in 1916 and drawn by Charles Léandre. Titled La séance continue (“The session continues”), it indicts the theater of official deliberation, portraying meetings and debate as self-perpetuating rituals detached from action.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

An examination of circular authority and the transformation of procedure into power.

The image presents obedience as an end in itself, where rules persist even after purpose disappears. Authority asserts legitimacy through repetition and compliance, exposing how bureaucratic systems maintain control by mistaking activity for meaning.

Historical Note

This cartoon was published in 1916 in La Baïonnette and was drawn by Ray Ordner. It targets the circular logic of authoritarian bureaucracy, depicting an official ordering documents to be sorted and then destroyed, satirizing power exercised through procedure rather than outcome.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

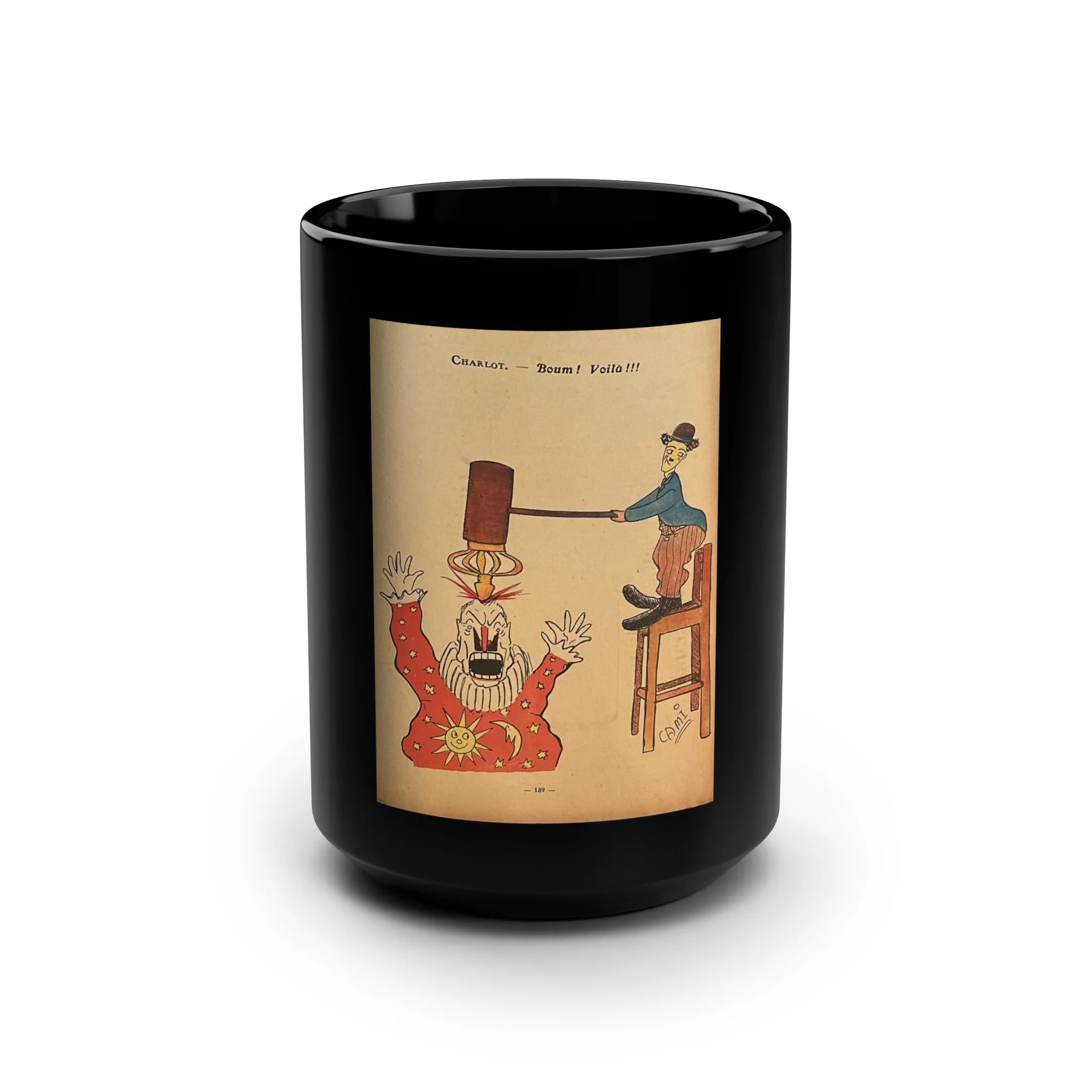

A satirical critique of wartime pomposity and the collapse of power into farce.

The image reduces imperial authority to theatrical excess, where costumes and symbols invite ridicule rather than obedience. Violence becomes comic, performance replaces command, and swagger collapses under the weight of its own spectacle.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in a 1917 issue of La Baïonnette and was created by Pierre-Henri Cami. Using the figure of Charlot, it turns an encounter with the Kaiser into slapstick, mocking imperial ambition through exaggerated props and physical comedy.

See the full Cami: Charlie Chaplin Collection here

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

Satire aimed at authoritarian vanity and the theatrical staging of power.

The image frames empire as a childish performance, where ambition seeks validation through spectacle rather than consent. Authority invites participation in its own myth, only to be met with refusal, exposing how fragile domination becomes once its illusions are challenged.

Historical Note

This caricature appeared in a 1917 issue of La Baïonnette and was created by Pierre-Henri Cami. Using Charlie Chaplin’s screen persona “Charlot,” it mocks Kaiser Wilhelm II’s imperial pretensions, puncturing the fantasy of world domination through humor and refusal.

See the full Cami: Charlie Chaplin Collection here

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

An examination of emotional substitution and the management of fear through symbol.

The image presents intimacy as something compressed and portable, where affection is converted into an object meant to steady the bearer. Comfort appears ritualized rather than relational, suggesting how war reshapes private attachment into a tool for endurance amid industrial violence.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in a January 1917 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Fabien Fabiano. Titled Fétiches et Mascottes, it reflects wartime practices that encouraged soldiers to rely on talismans and symbolic objects as emotional stabilizers.

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

No results found

No results match your search. Try removing a few filters.

The image presents violence as performance, where swagger and threat are recast as cultural celebration. Authority emerges through fear rather than consent, suggesting how mythmaking can sanitize coercion and turn mob rule into costume.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in an 1889 issue of Judge magazine. Titled with a play on “Shanty Claws,” it mocks the romanticized Wild West by portraying armed frontiersmen halting a stagecoach, warning that violence wrapped in folklore remains a threat to the common good.

Enamel mug | Stainless steel core | Lead- and BPA-free | Hand wash only

Add two mugs to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.