Pierre-Henri Cami:

Charlie Chaplin Collection

Humor against tyranny in wartime France

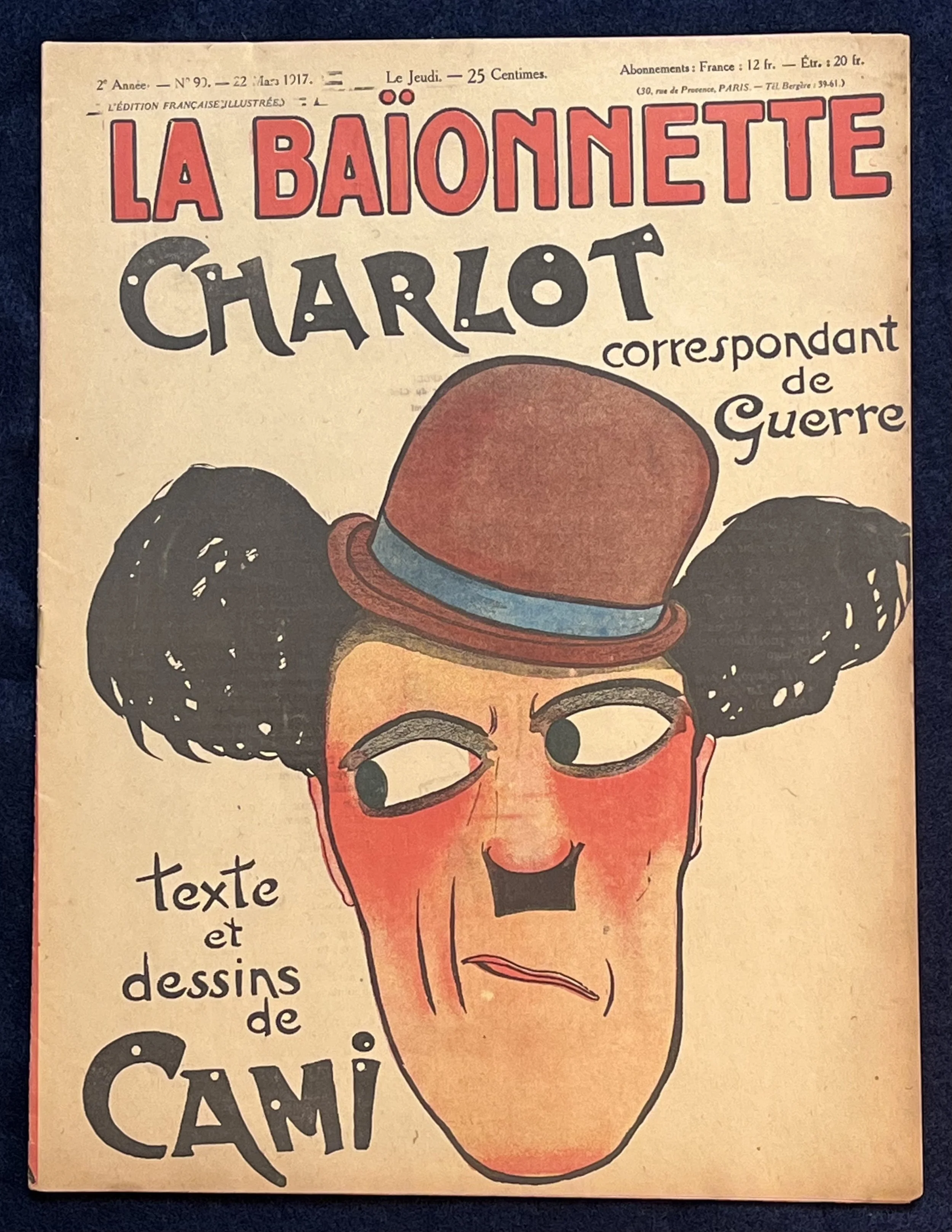

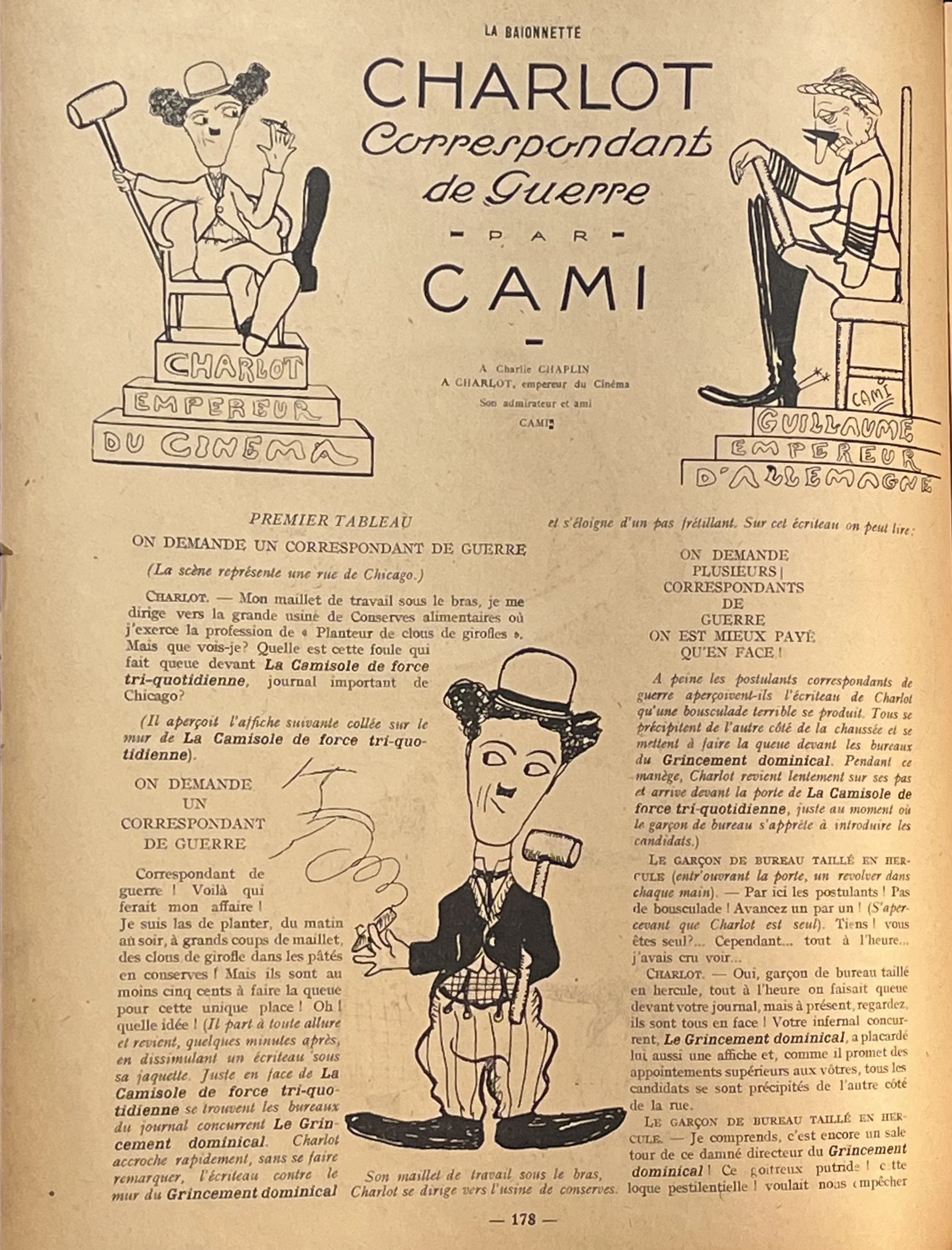

Pierre-Henri Cami (1884-1958) was a French humorist, writer and cartoonist whose blend of absurdity and caricature earned him wide popular success from the 1910s onward. His drawings for La Baïonnette placed “Charlot” and contemporary figures—often including “the Kaiser” (Wilhelm II)—into exaggerated comic encounters that highlighted the theatrical side of political and military life. Cami’s distinctive line work and burlesque imagination allowed him to critique authority through humor rather than direct polemic, giving his wartime illustrations a tone that is playful, pointed and unmistakably his own.

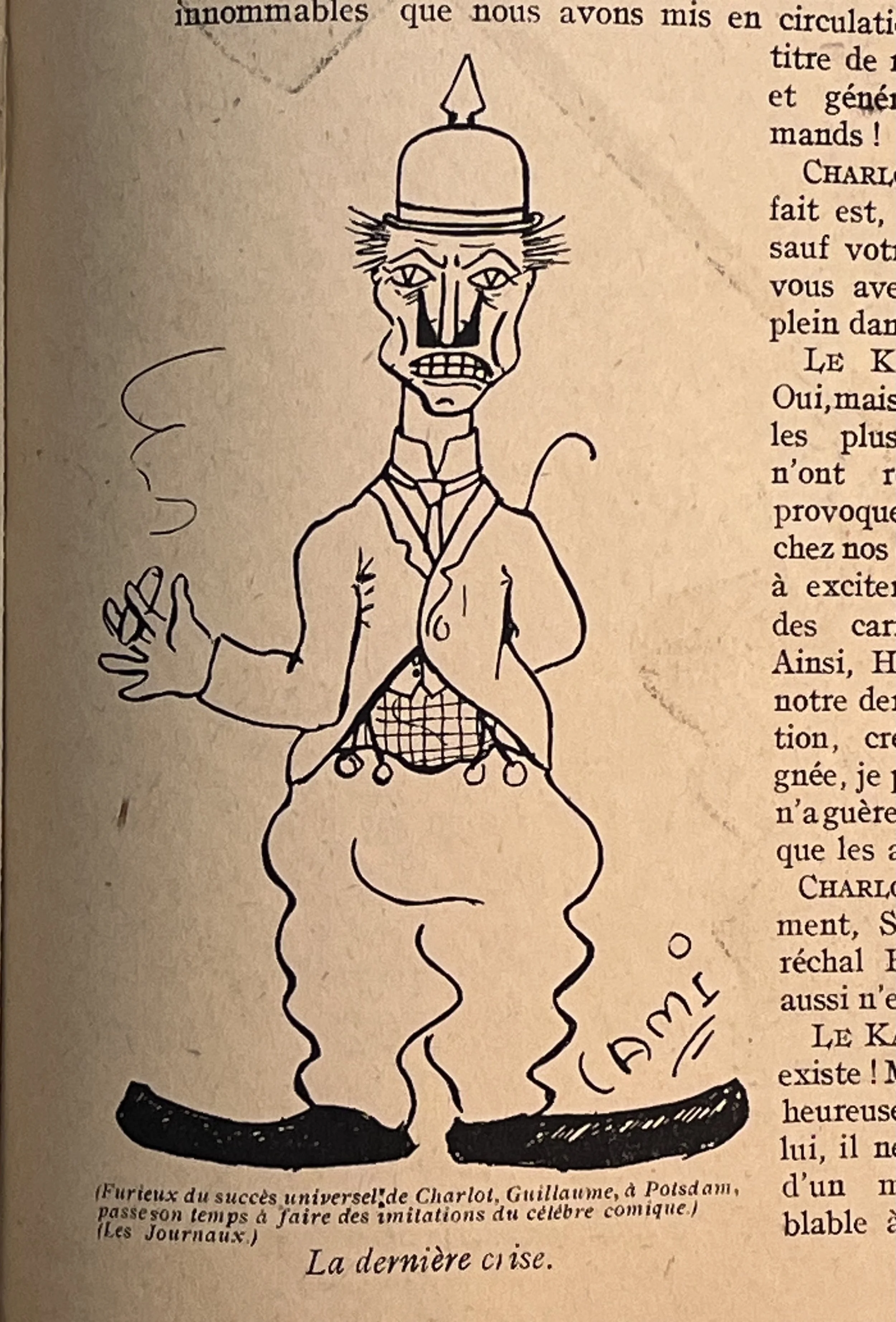

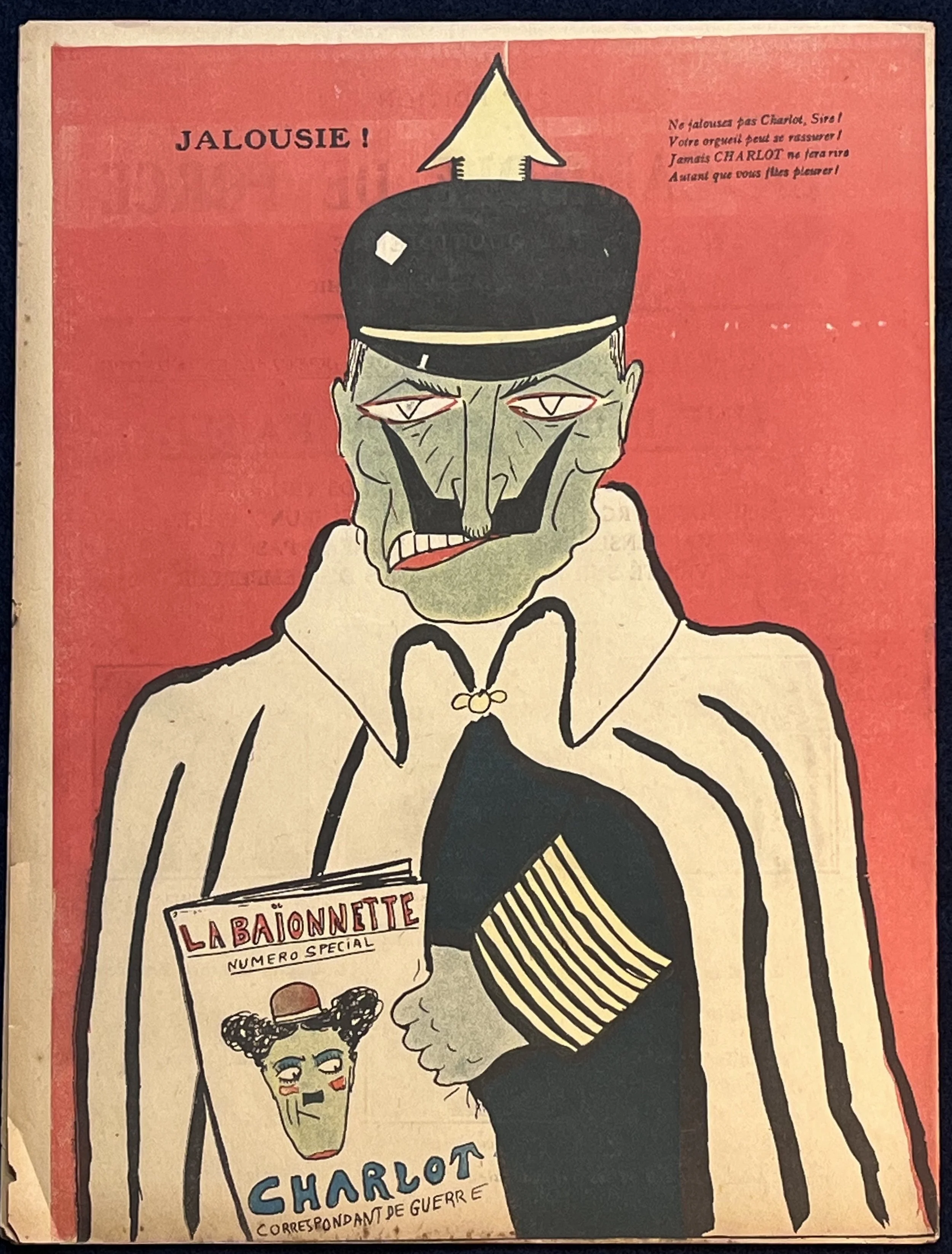

Cami turns the Kaiser into a deranged imitator of Chaplin, flailing with a mallet he mistakes for slapstick but which the poem identifies as “the butcher’s bloody hammer” (le maillet sanglant du boucher). The cartoon ridicules the emperor’s hysterical self-performance—part costume, part tantrum—as he postures in Potsdam unaware that his theatrics end in real violence.

In the accompanying sketch, Cami reduces the Kaiser to a taut, almost trembling outline, echoing the newspapers’ note that Wilhelm II, furious at Charlot’s universal success, spent his days in Potsdam mimicking the famous comic. Stripped of color and swagger, the drawing reveals a late-war authority fraying into parody— “the last hysterical attack” (la dernière crise) in its barest form.

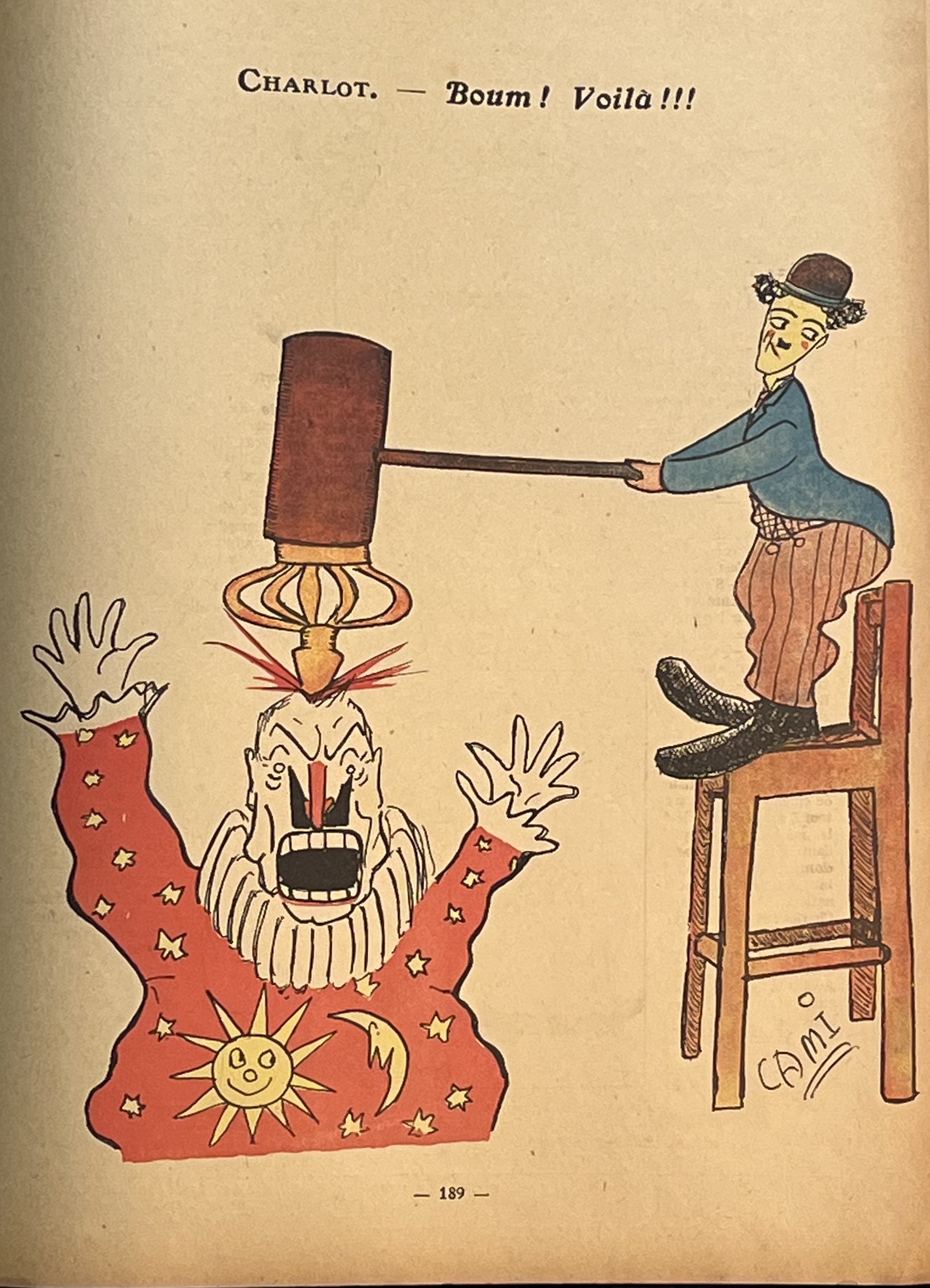

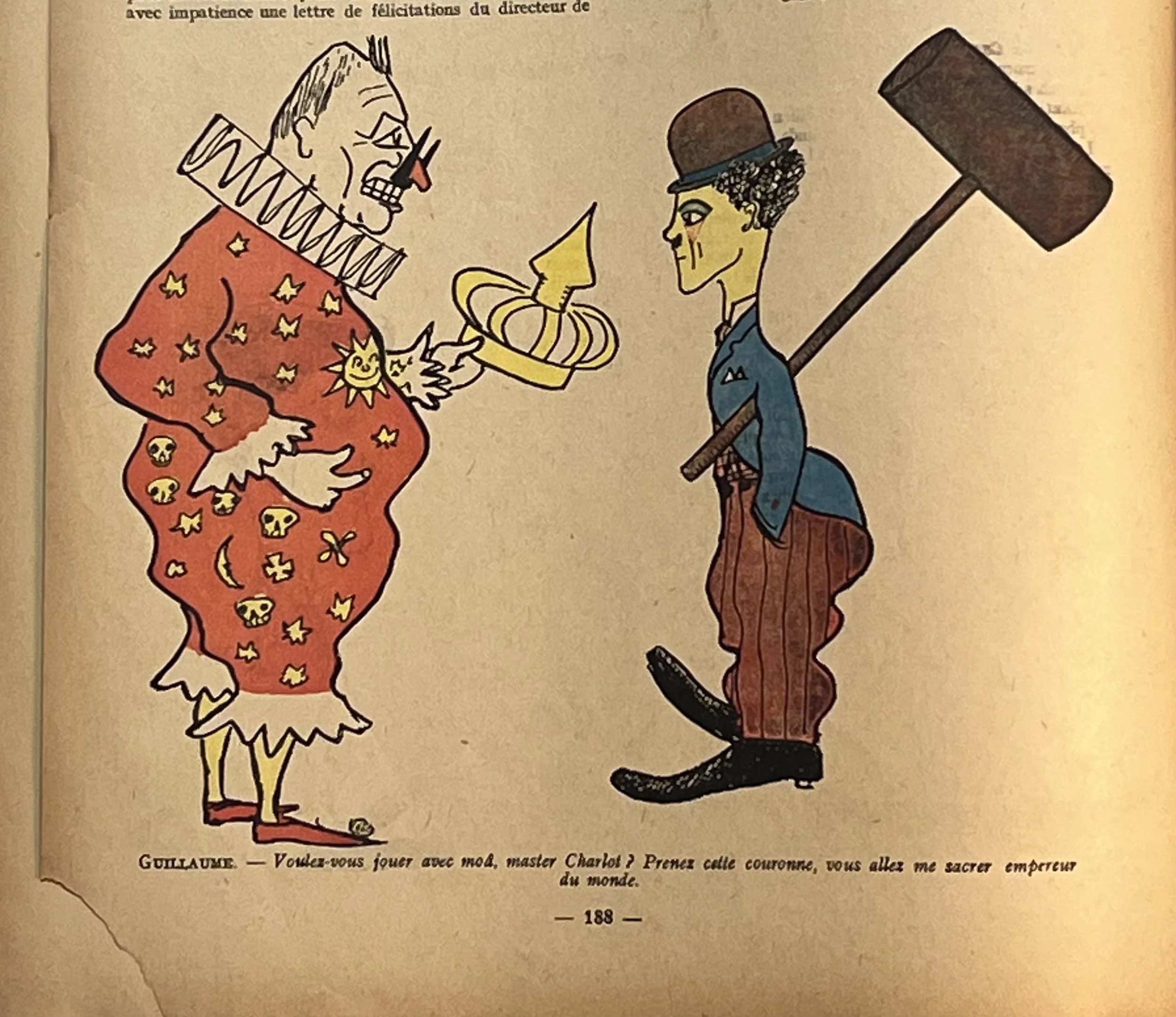

Cami stages a farcical duel between Charlot and a clownish Kaiser, using outsized props—a crown, a mallet, and exaggerated costumes—to expose the theatrical absurdity of imperial ambition. The Kaiser’s star-covered robe and fixed grin heighten the sense of delusion and pretense.

In the accompanying scene, Charlot turns the ritual on its head, reversing the imperial hierarchy with comic bluntness. Cami’s humor rests in these visual contradictions, where slapstick becomes a pointed commentary on the fragility of wartime authority.

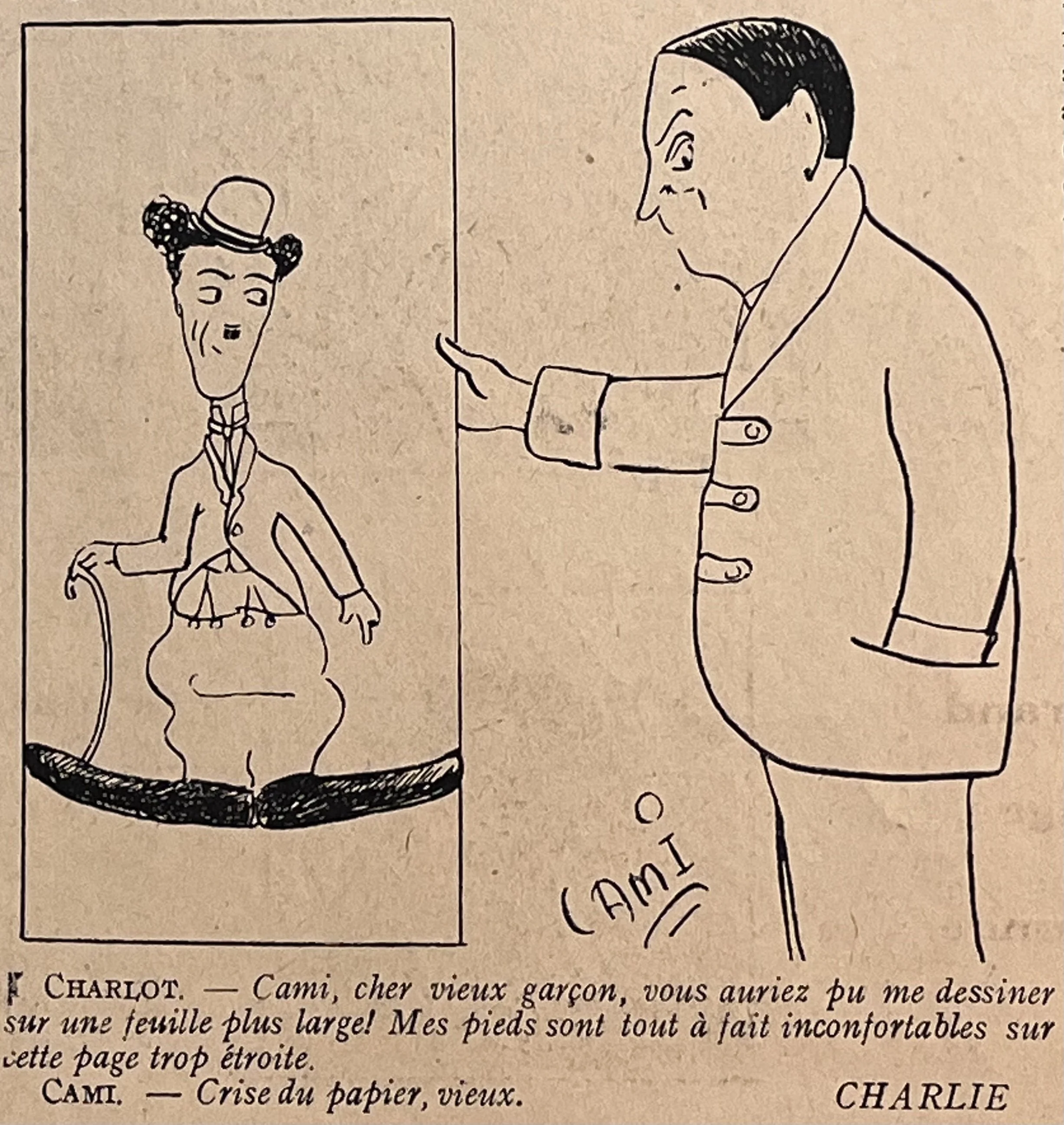

Cami plays with self-reference in these minimalist drawings, placing Charlot in quiet, slightly awkward wartime routines—receiving a registered letter, or confronting his own cramped likeness. The pared-down line work carries the understated humor, letting small gestures do the comic lifting.

In each vignette, the humor turns on scale and constraint: oversized envelopes, pages drawn too narrow, and Charlot boxed in by his own paper. The French captions underline the joke, with Charlie complaining about cramped feet and Cami blaming a “paper crisis” (Crise du papier). Even these modest scenes carry Cami’s dry, self-aware charm.

In this final image, Cami heightens the rivalry between Charlot and the Kaiser into a bold, poster-like composition. The stark red ground and exaggerated features push the Kaiser toward pure caricature, clutching a Baïonnette issue that celebrates Charlot instead. Cami’s humor lands in the contrast between swagger and insecurity, ending the series on a sharp, theatrical note.