From the archives of political satire

these works preserve a tradition of dissent—

continuing its vigilance in the present.

From the archives of political satire

these works preserve a tradition of dissent—

continuing its vigilance in the present.

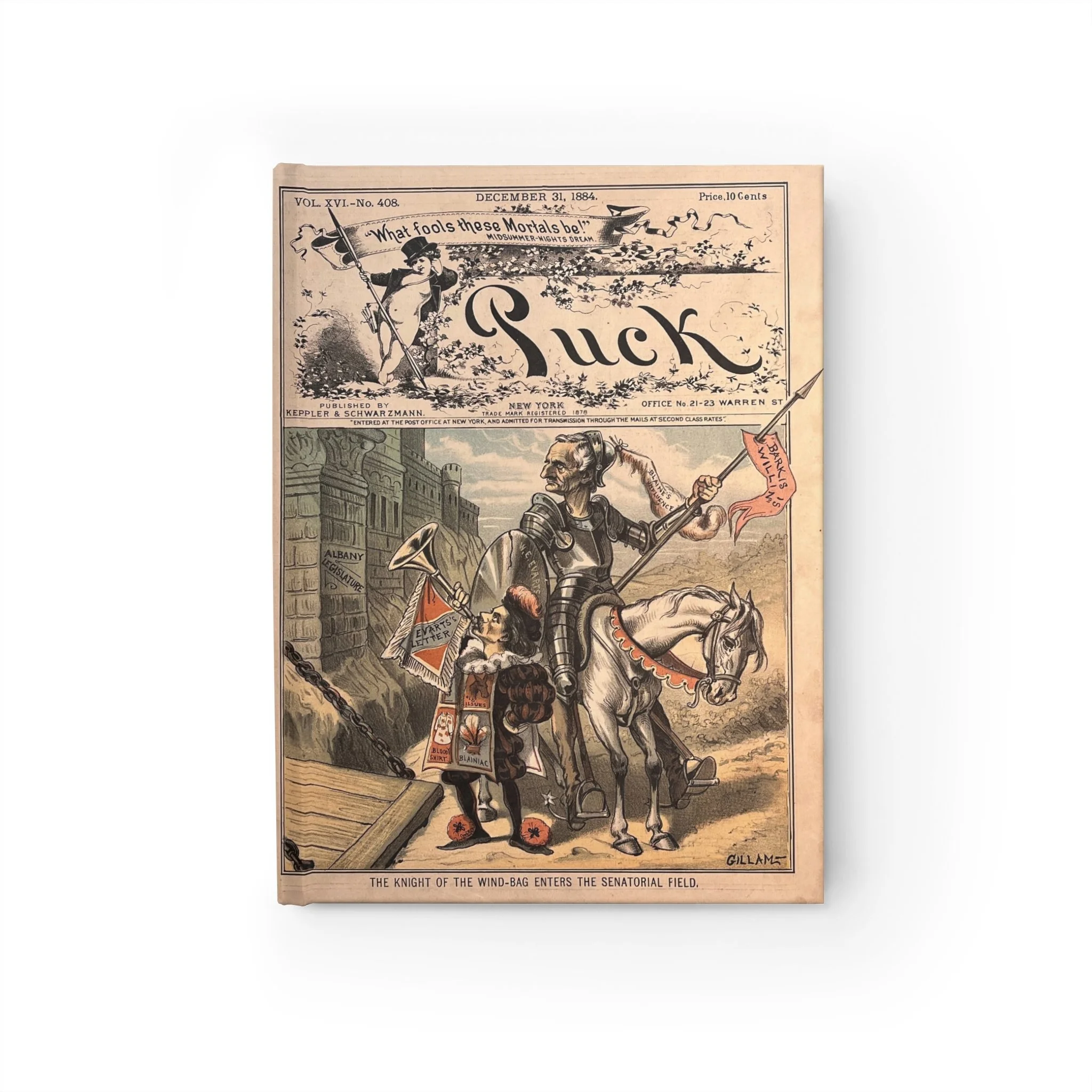

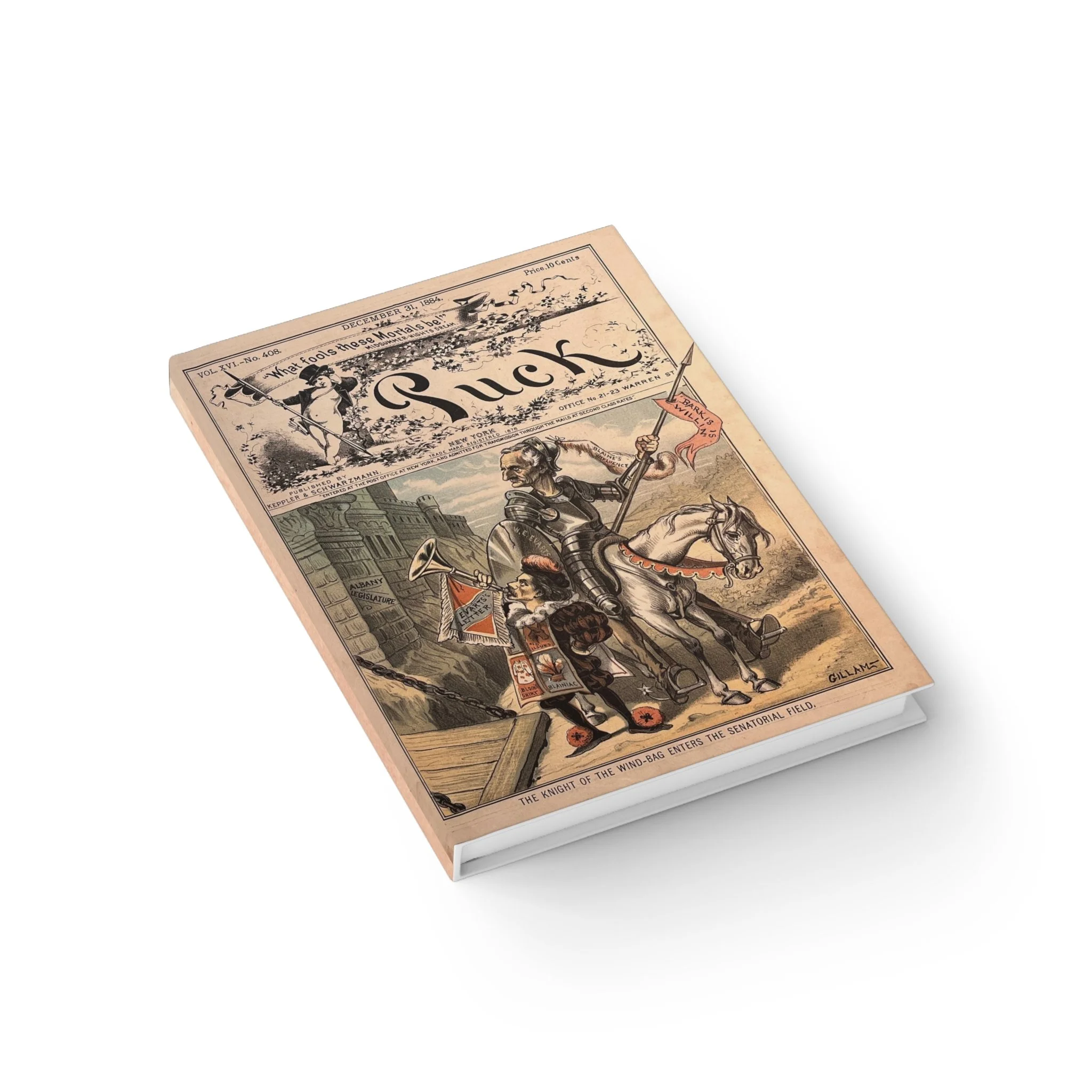

Satire aimed at political performance and empty display.

When ambition is staged through slogans and props rather than ideas and responsibility, spectacle begins to substitute for substance. That dynamic was already visible in the late nineteenth century—and it has never entirely disappeared.

Historical note:

The cover image comes from an 1884 issue of Puck magazine, illustrated by Bernhard Gillam, a leading Gilded Age political cartoonist known for satirizing corruption, ambition, and political spectacle.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

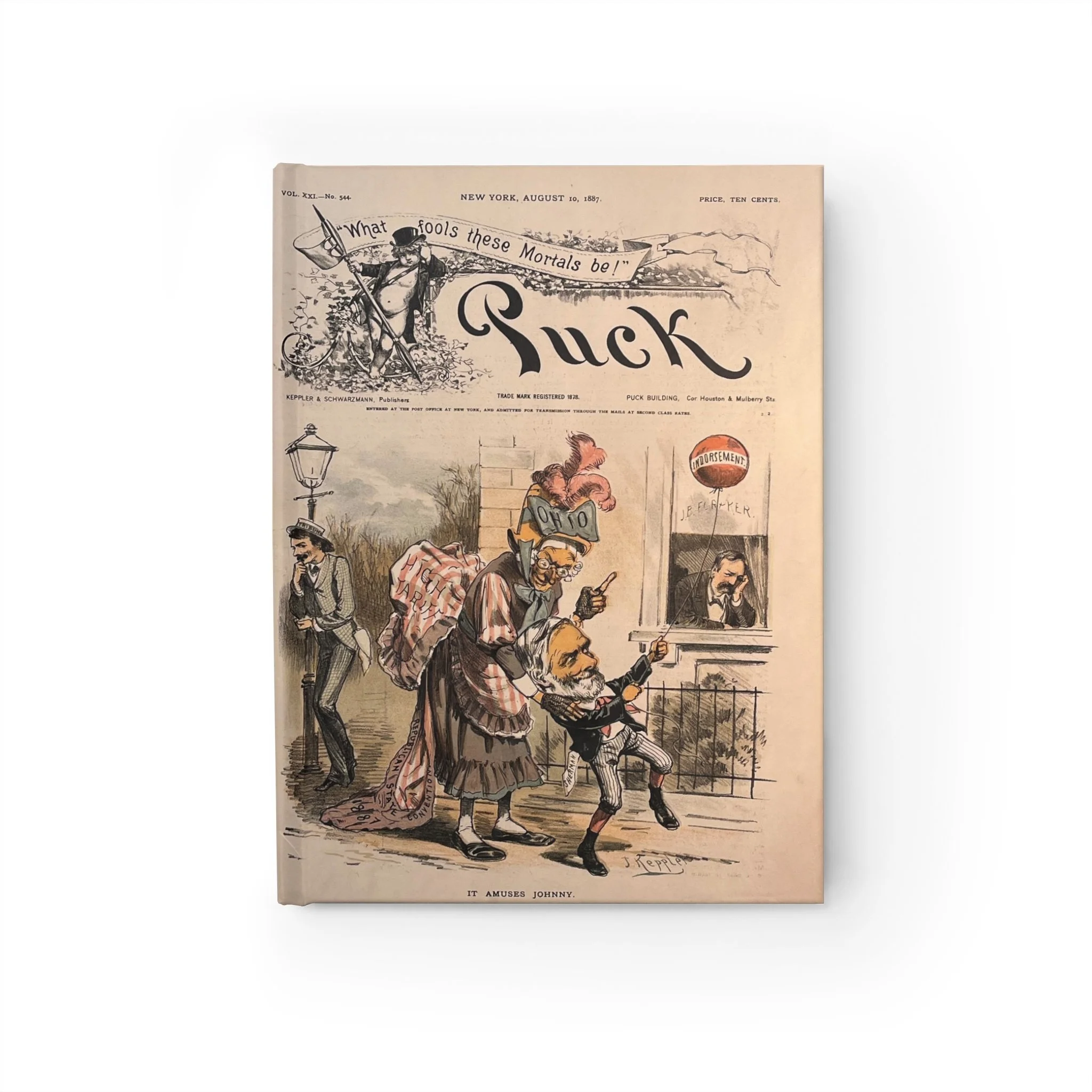

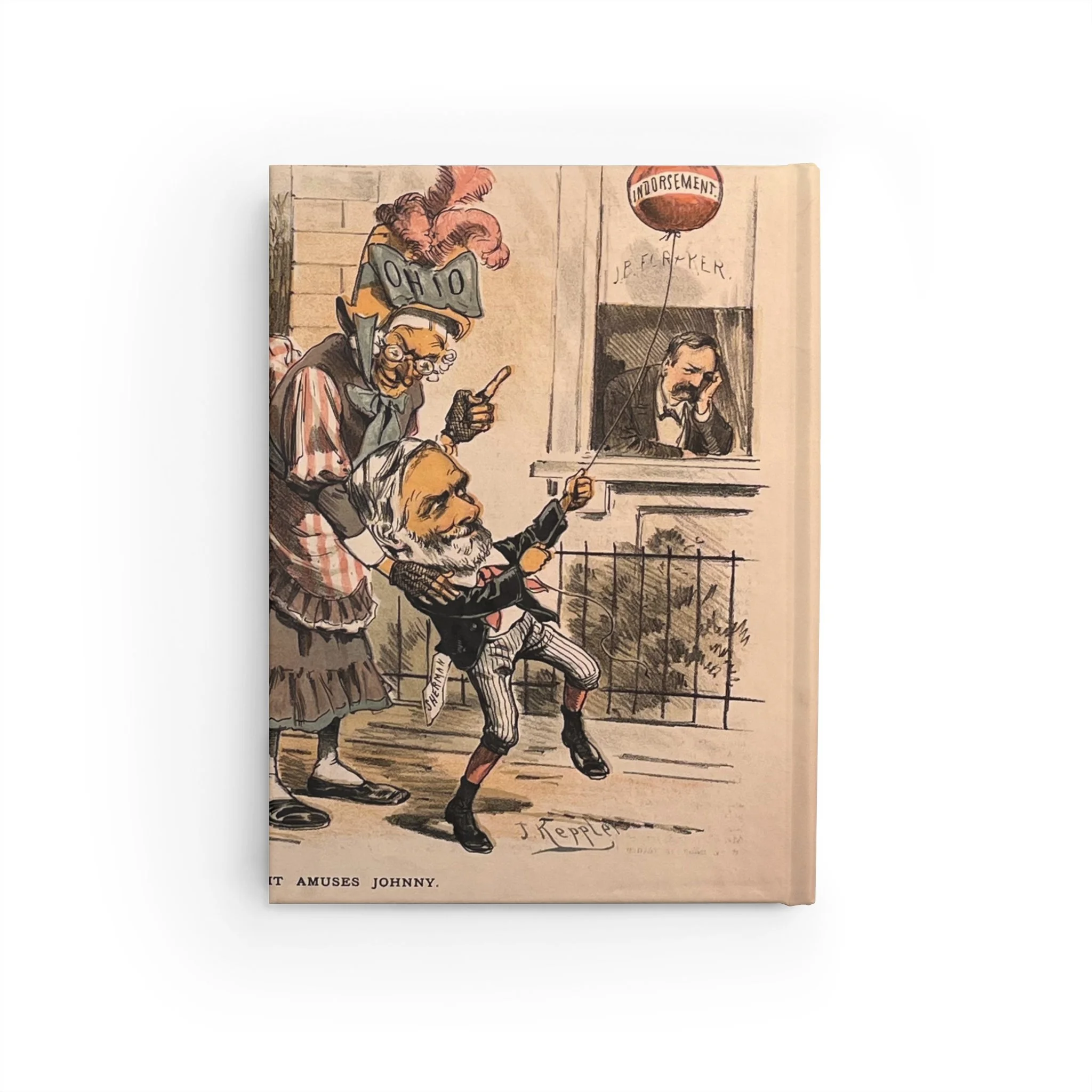

Satire directed at political management and performative ambition.

The image frames public life as something arranged rather than chosen, where candidates are advanced through routine gestures and institutional habit. Endorsement appears procedural and symbolic, suggesting a system in which display substitutes for deliberation.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in the August 10, 1887 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Joseph Keppler, whose work frequently critiqued party machinery and the theatrical character of late-nineteenth-century politics.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

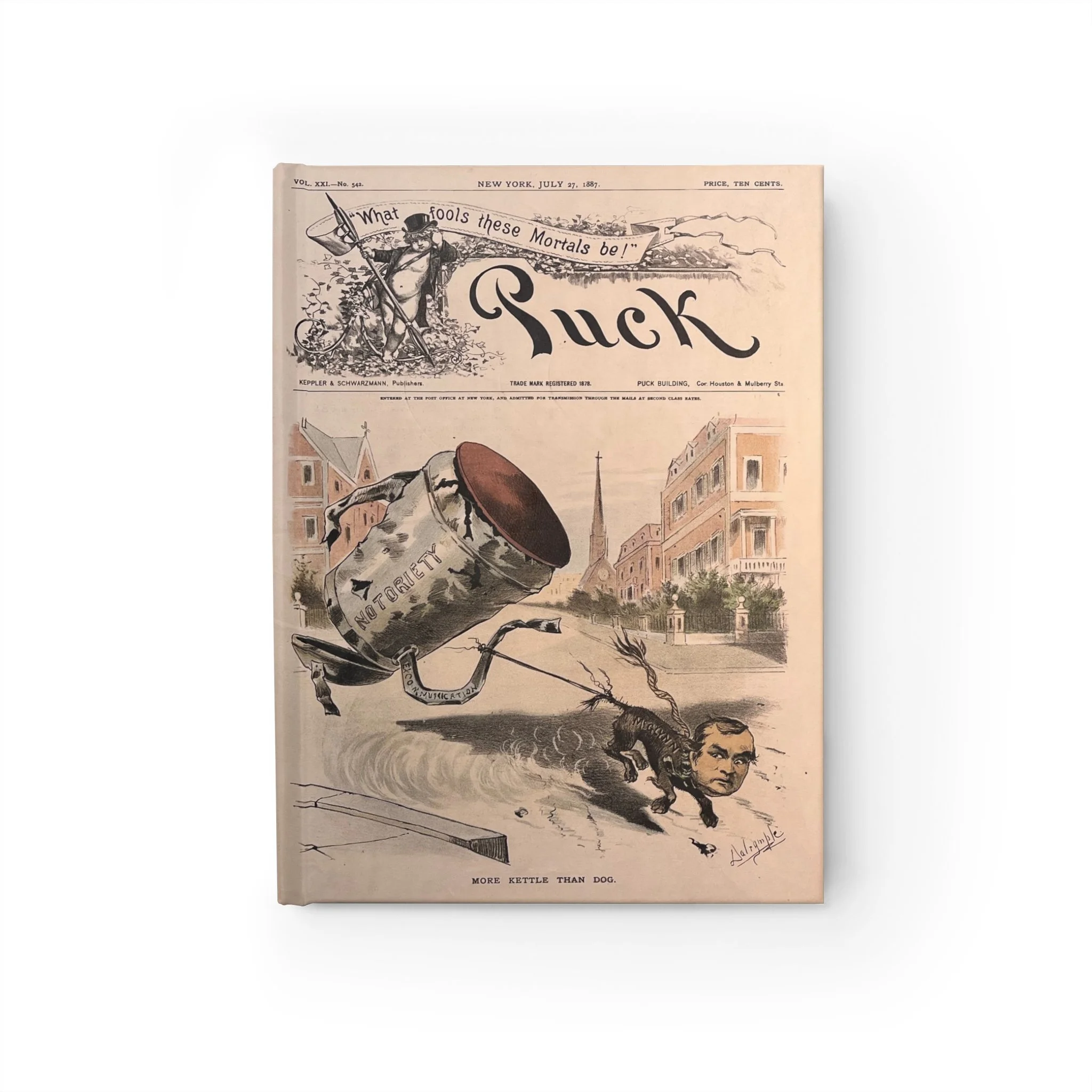

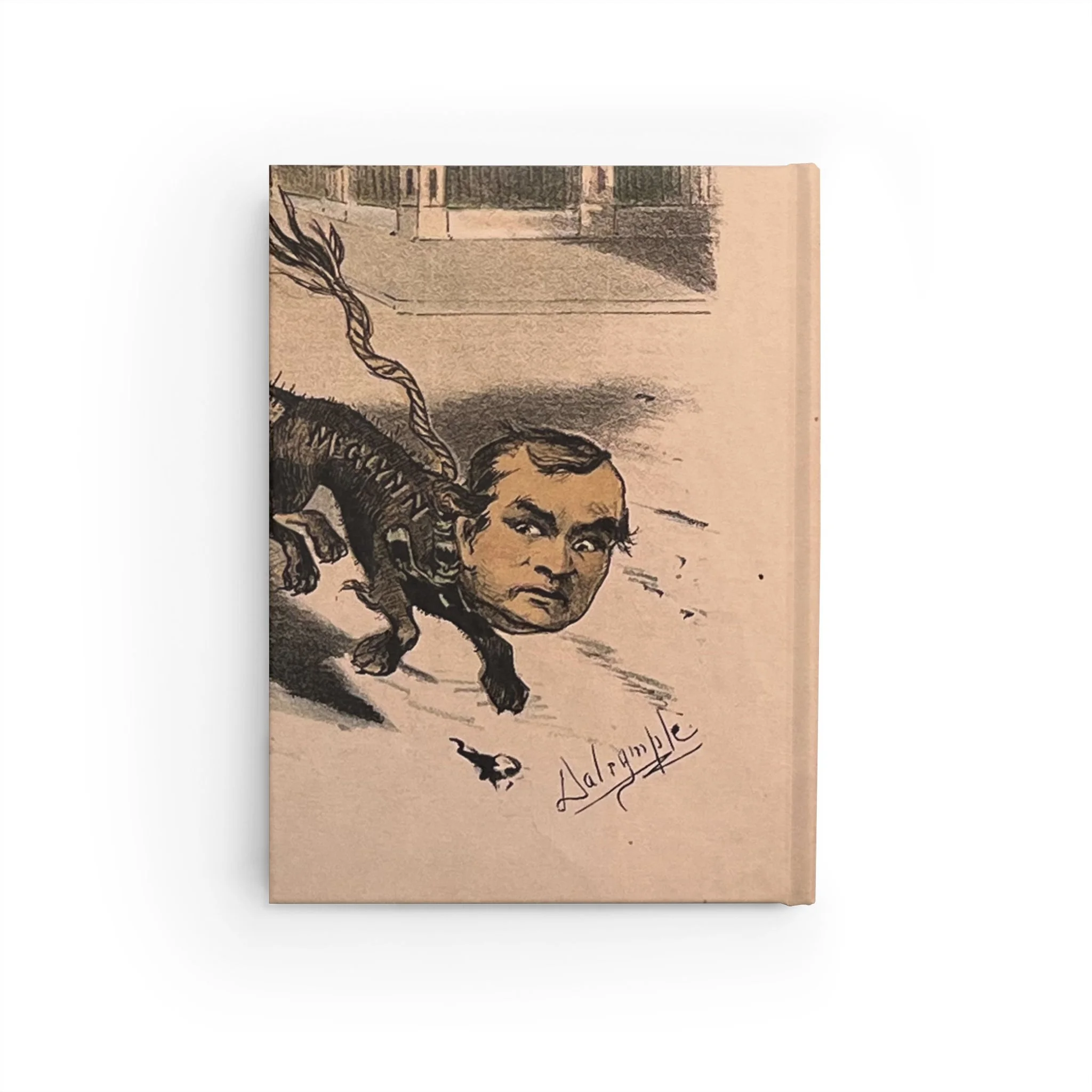

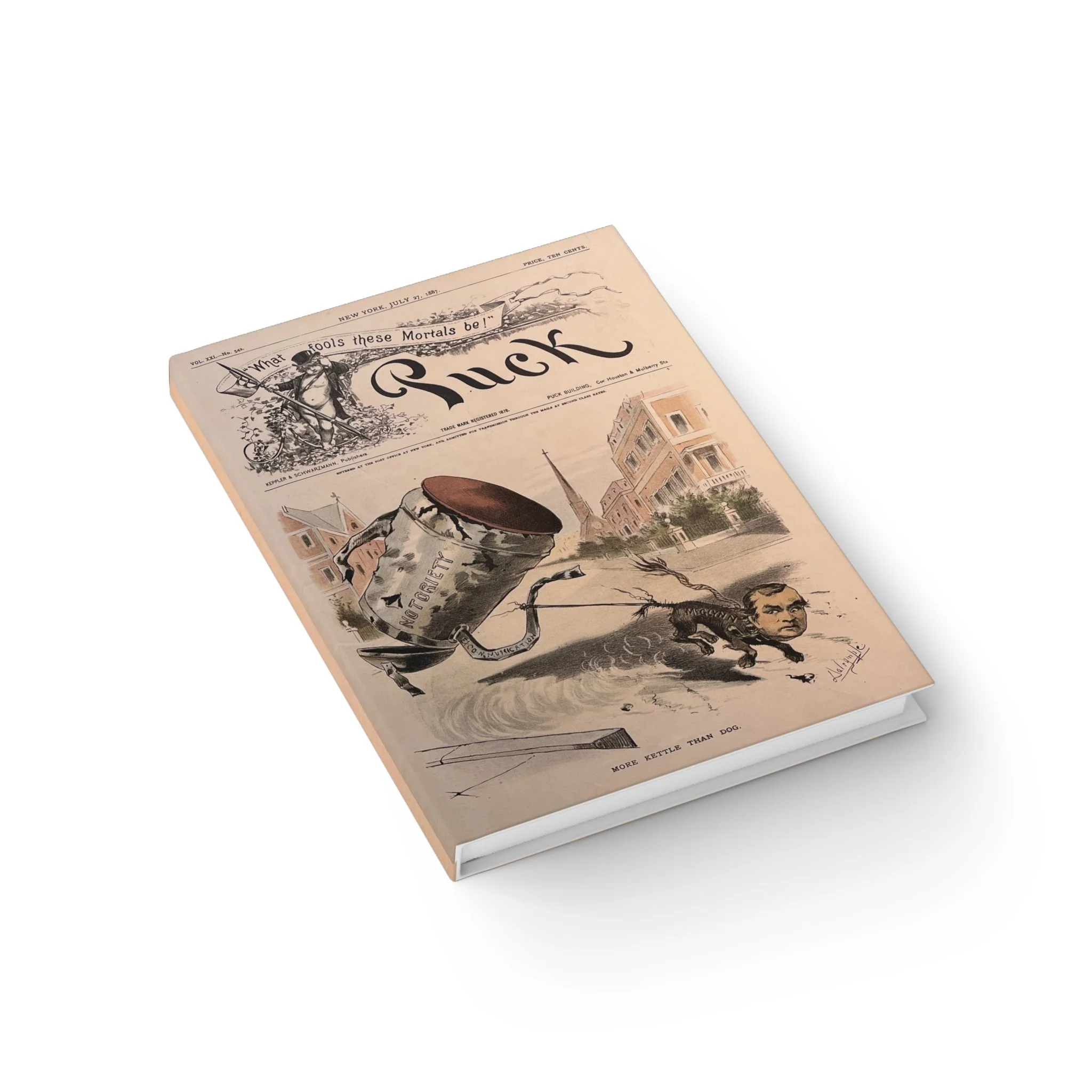

A satirical treatment of scandal, spectacle, and the inflation of moral outrage.

The image portrays notoriety as a force that grows beyond its original cause, pulling individuals along in its wake while punishment becomes performative rather than corrective. Public condemnation appears less about responsibility than about amplification, exposure, and control.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1887 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Louis M. Dalrymple, whose work frequently examined scandal, authority, and the theatrical use of shame in public life.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Blank | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

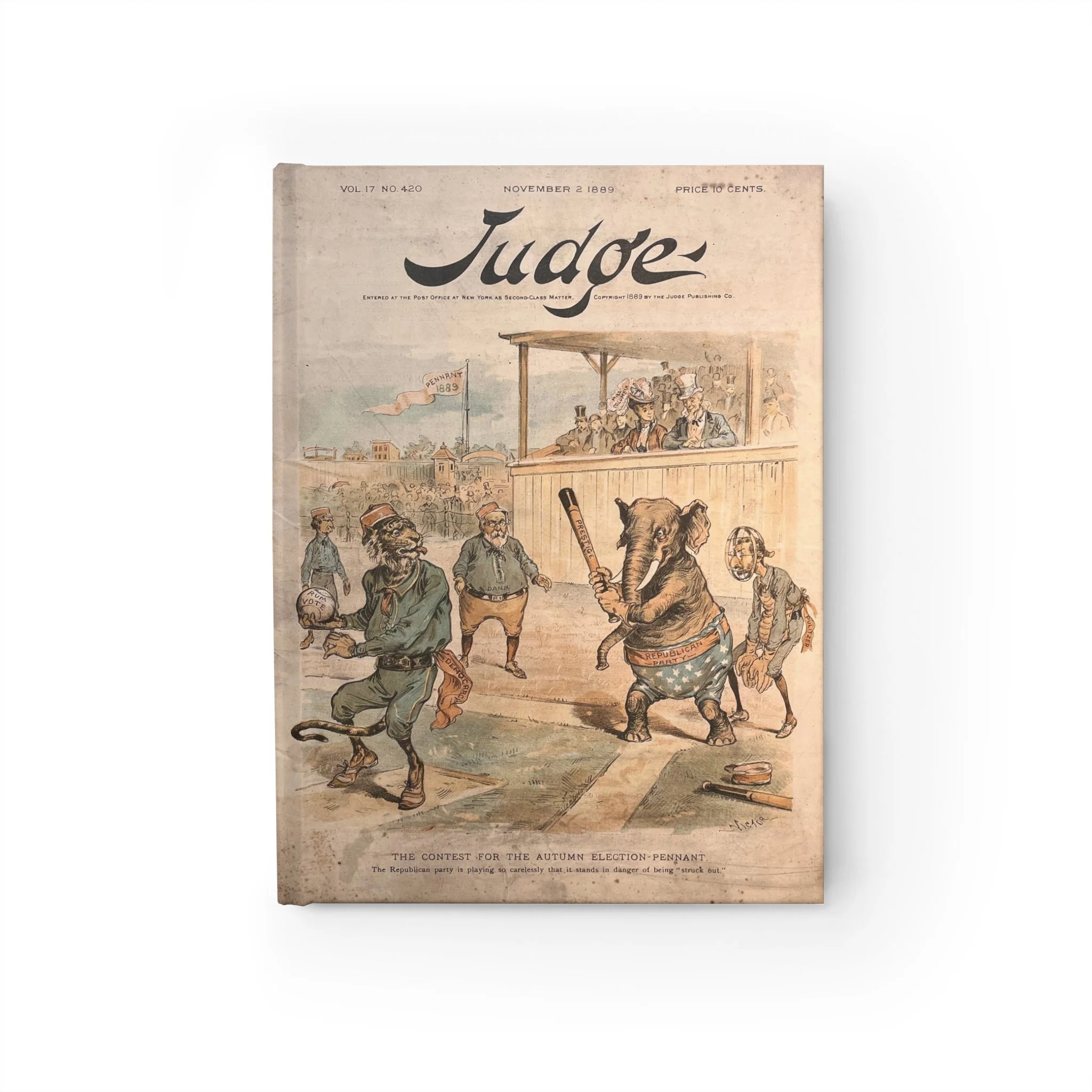

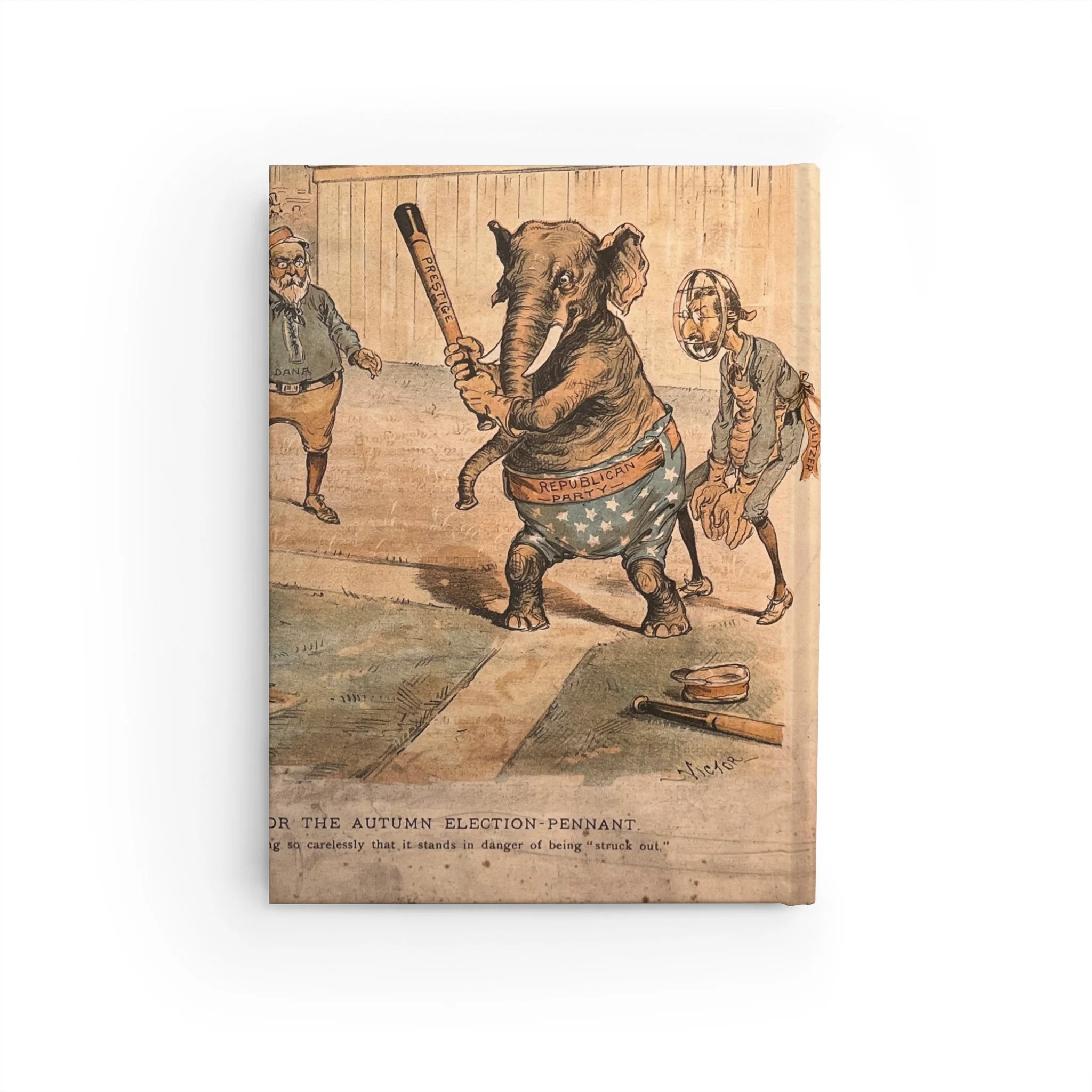

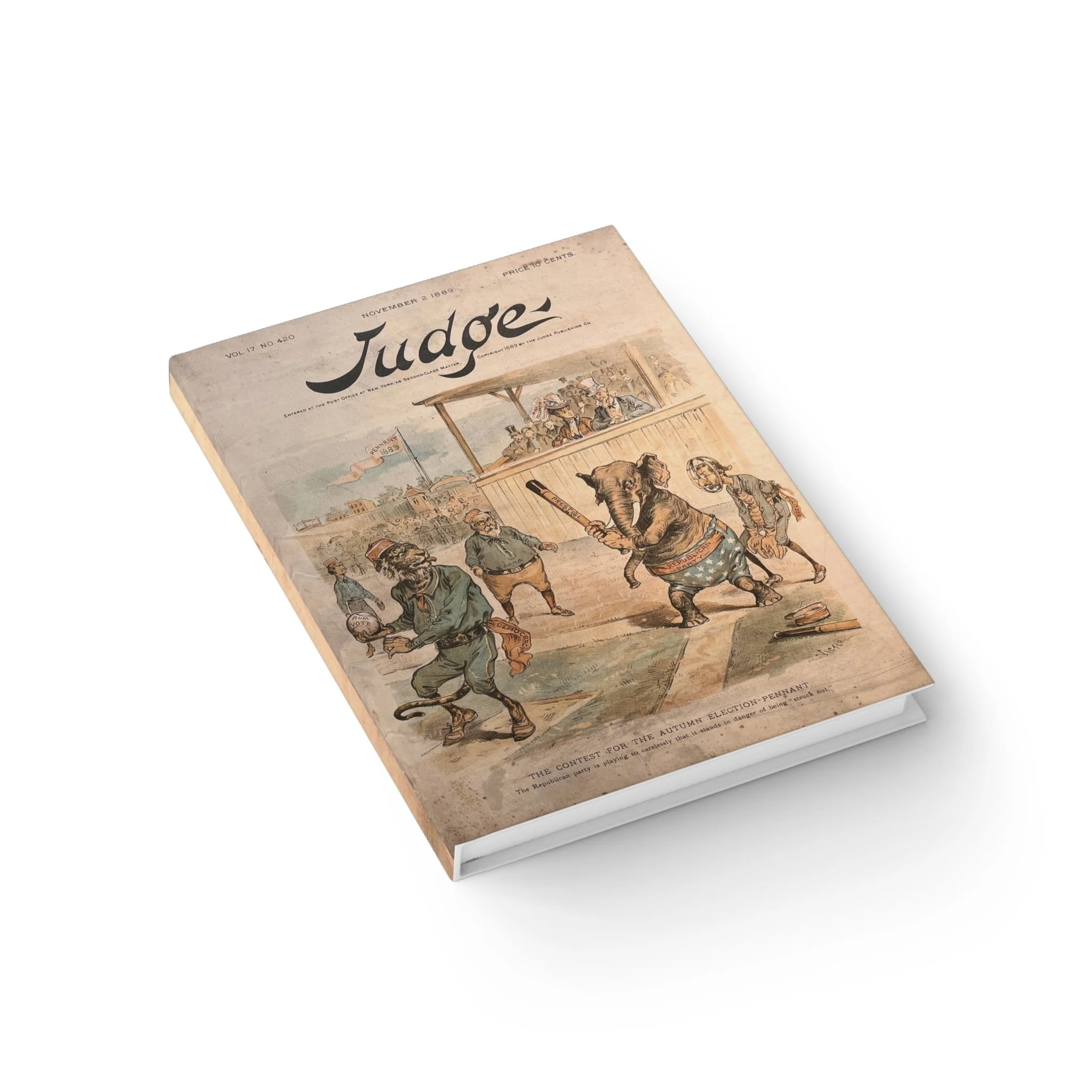

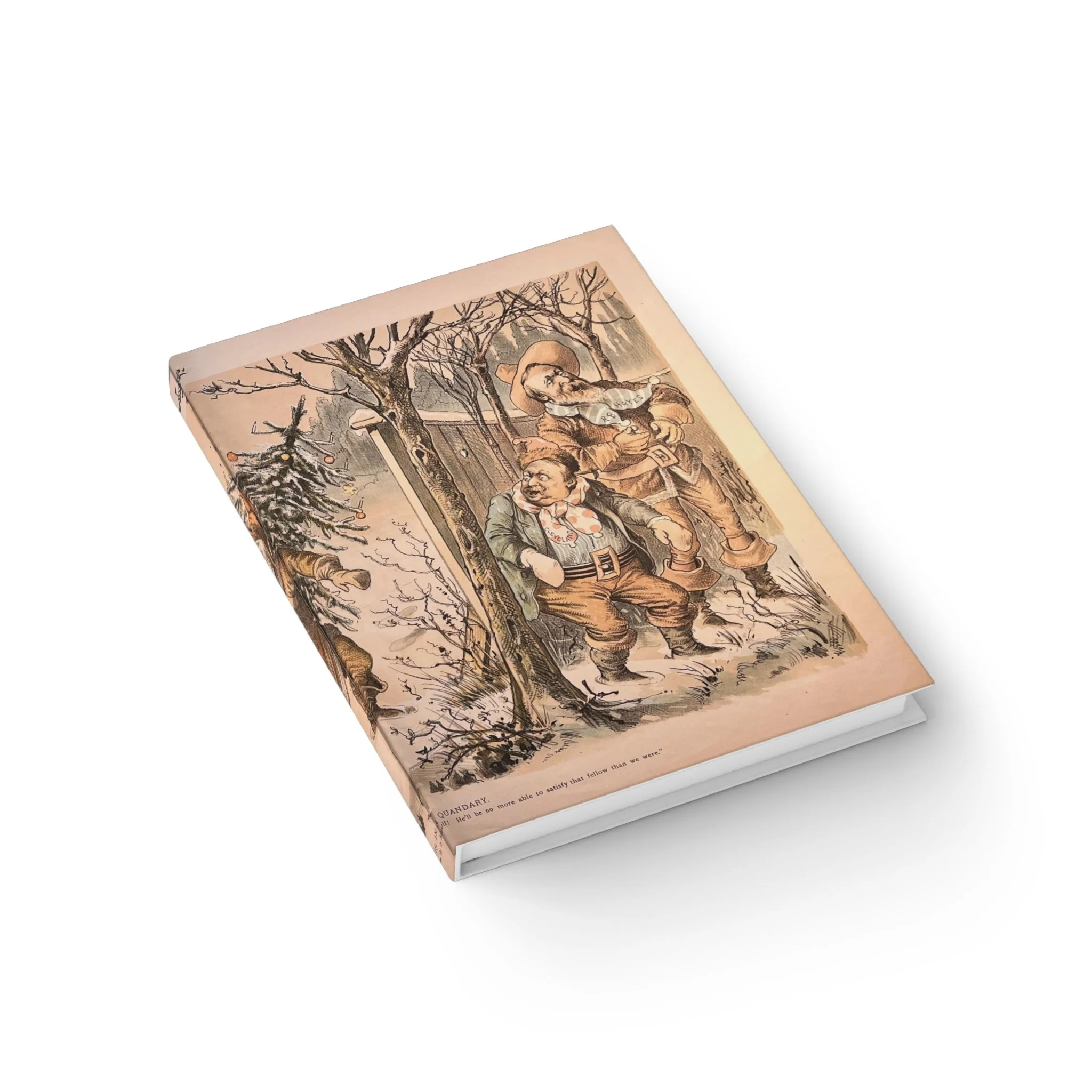

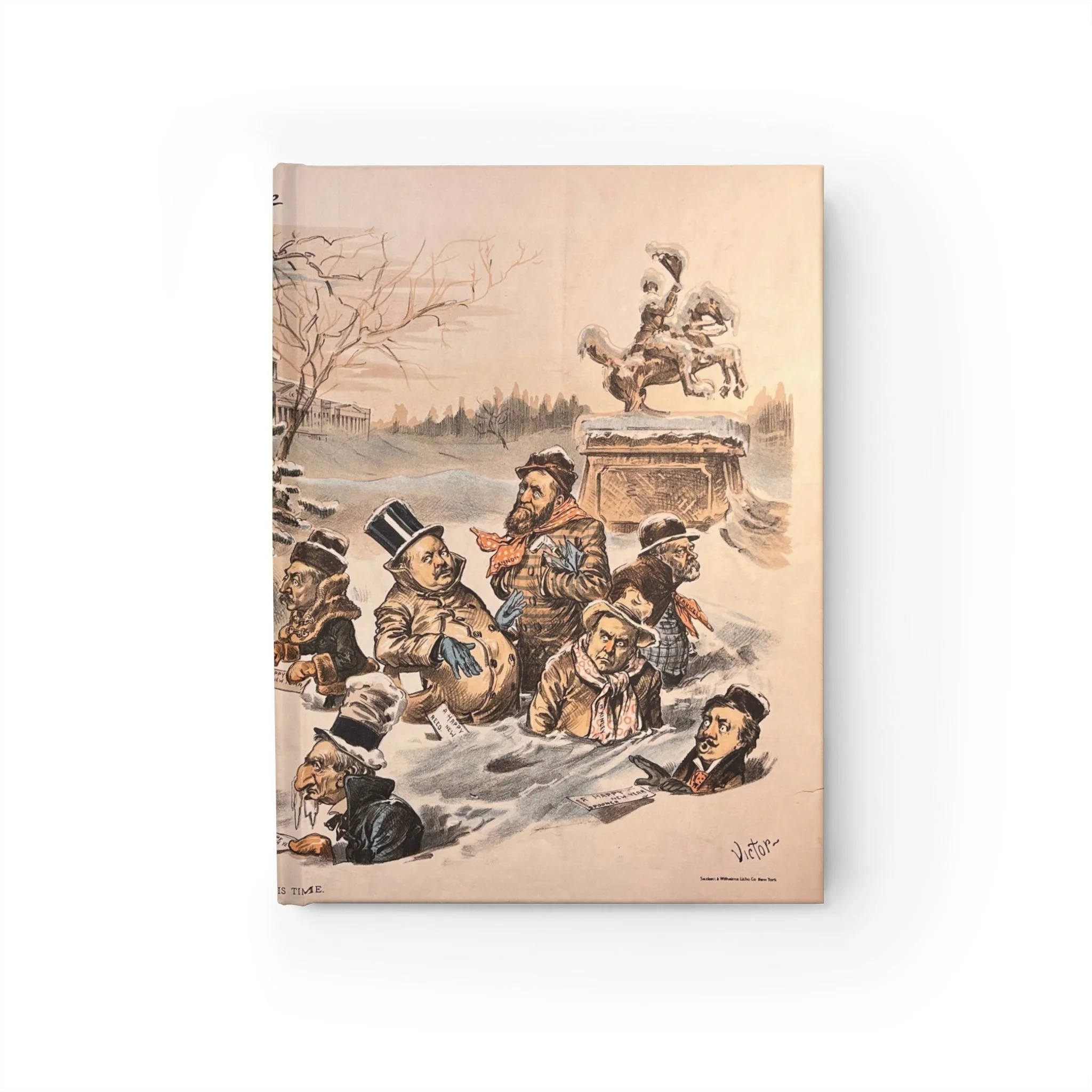

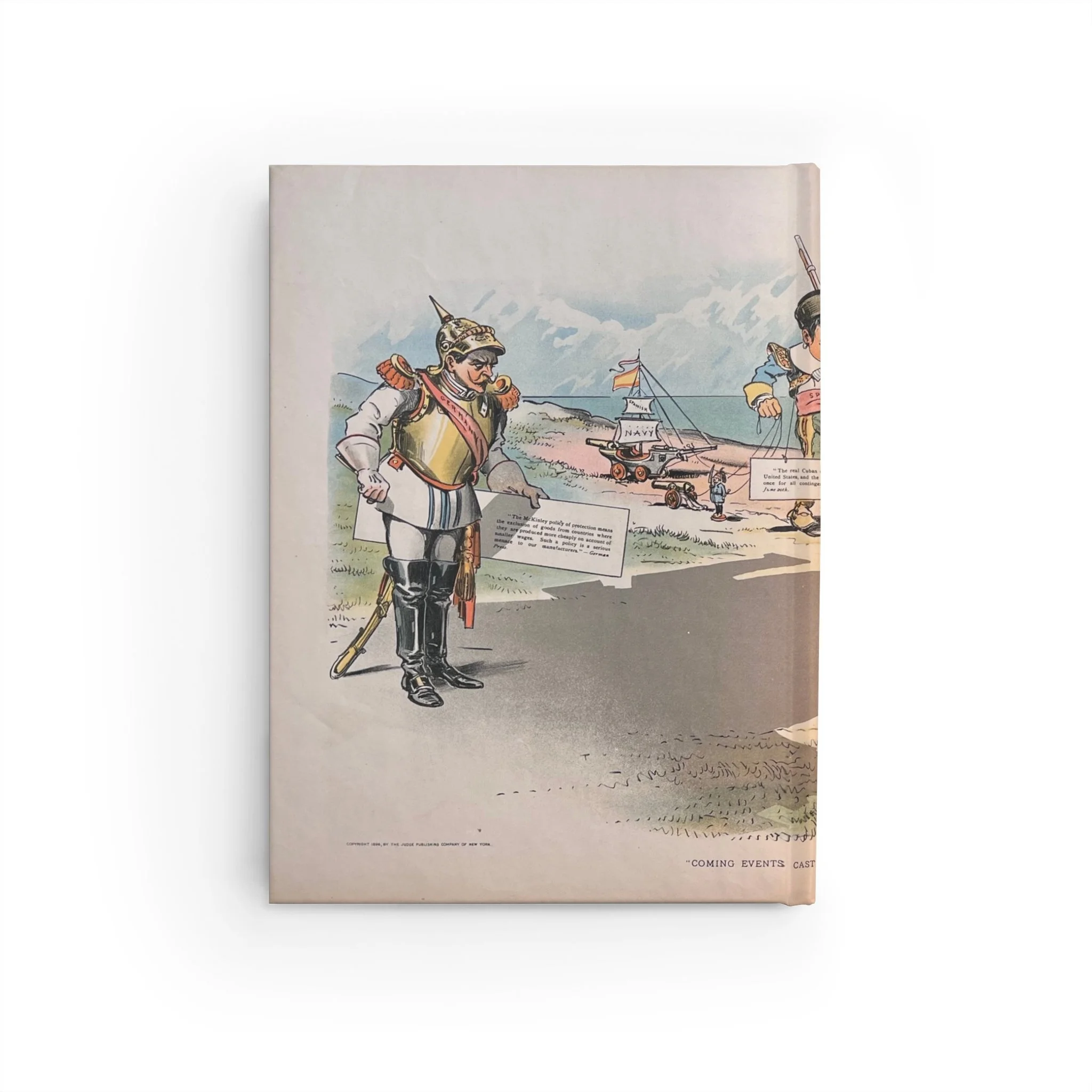

Satire focused on political complacency and the consequences of careless power.

The image frames electoral politics as a competitive arena where GOP misjudgment and overconfidence invite defeat. Authority appears inattentive and exposed, suggesting that dominance erodes when discipline gives way to entitlement and routine advantage.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1889 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam, a prominent political cartoonist of the Gilded Age known for his critiques of party politics, corruption, and electoral strategy.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Blank | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

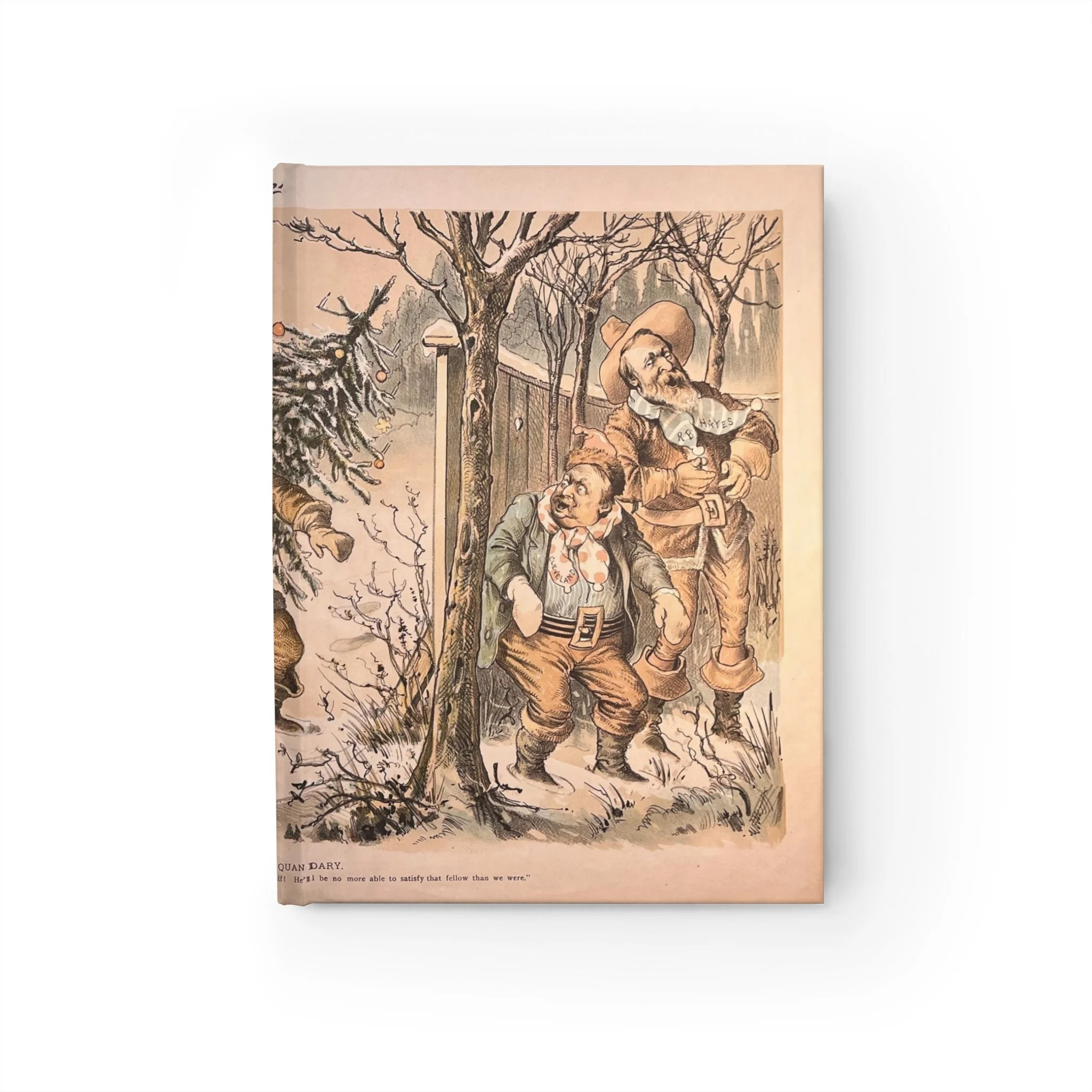

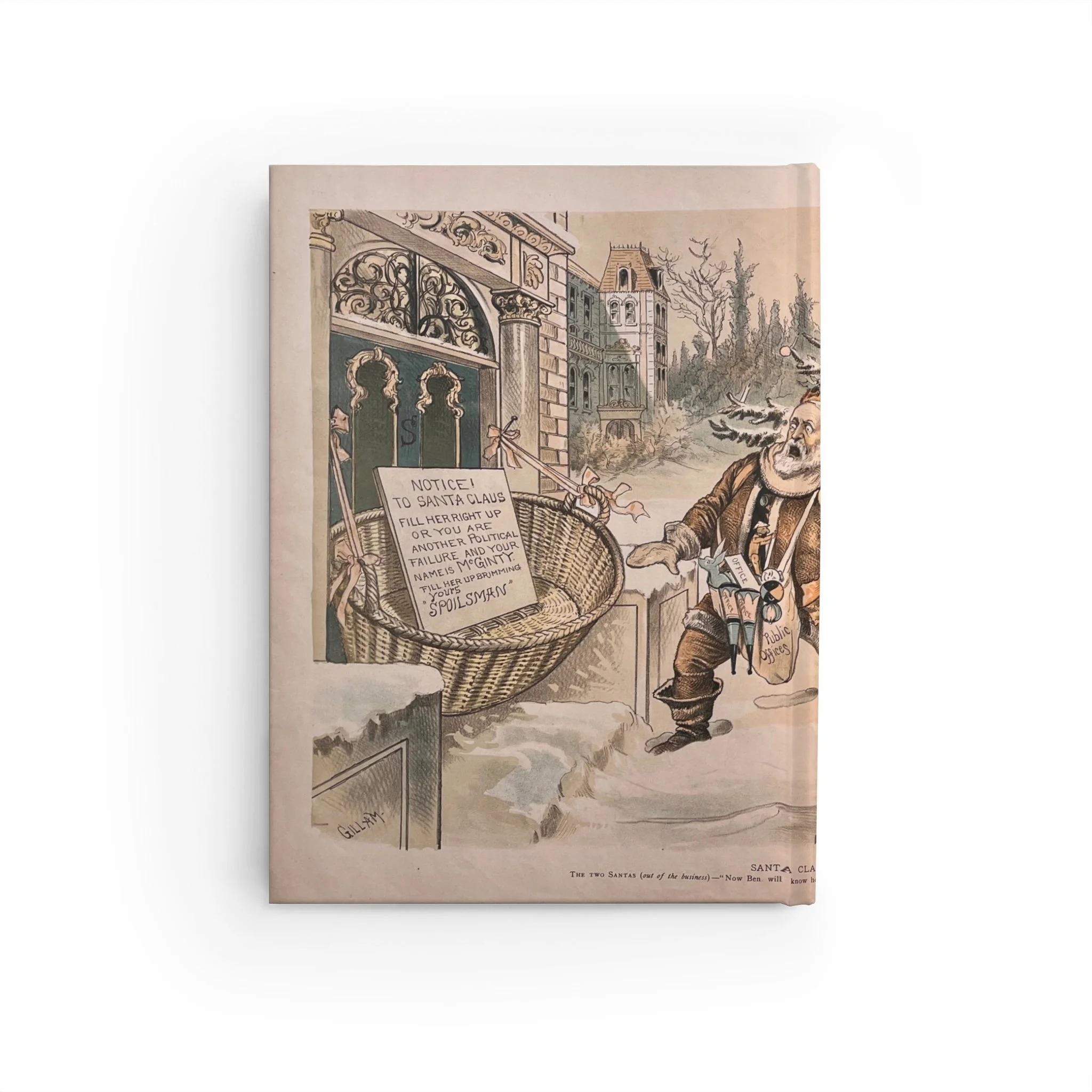

A satirical critique of political patronage and the exhaustion of governance under constant demand.

The image depicts public office as an endless burden rather than a position of service, where obligation multiplies and authority is measured by what can be distributed rather than what can be governed. Power appears transactional and unsustainable, suggesting a system in which pressure and loyalty eclipse responsibility.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in Judge magazine during the late nineteenth century and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. It satirizes the Republican spoils system of the Gilded Age, portraying the strain of patronage politics and the corrosive effects of party bosses exerting control over public office.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Blank | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

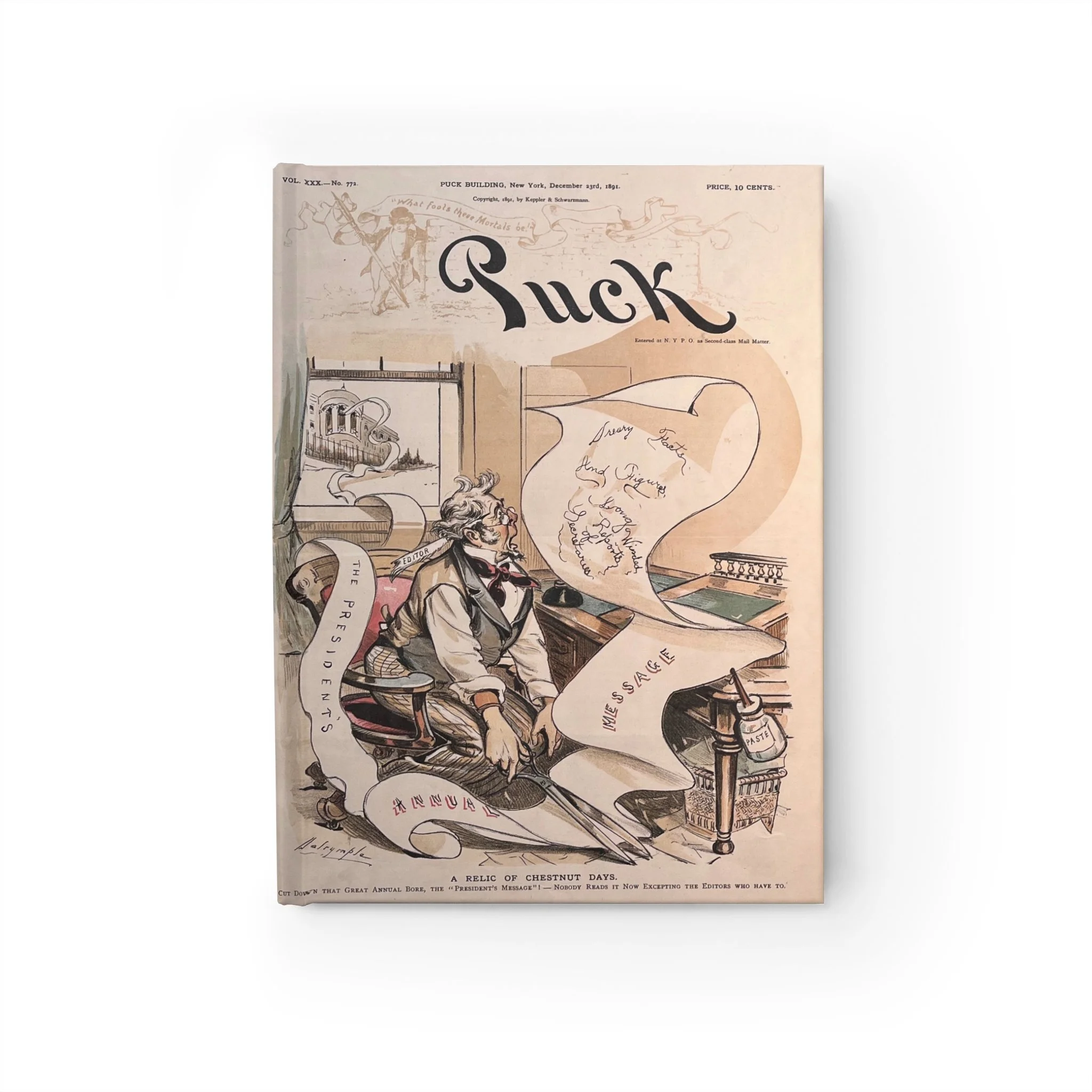

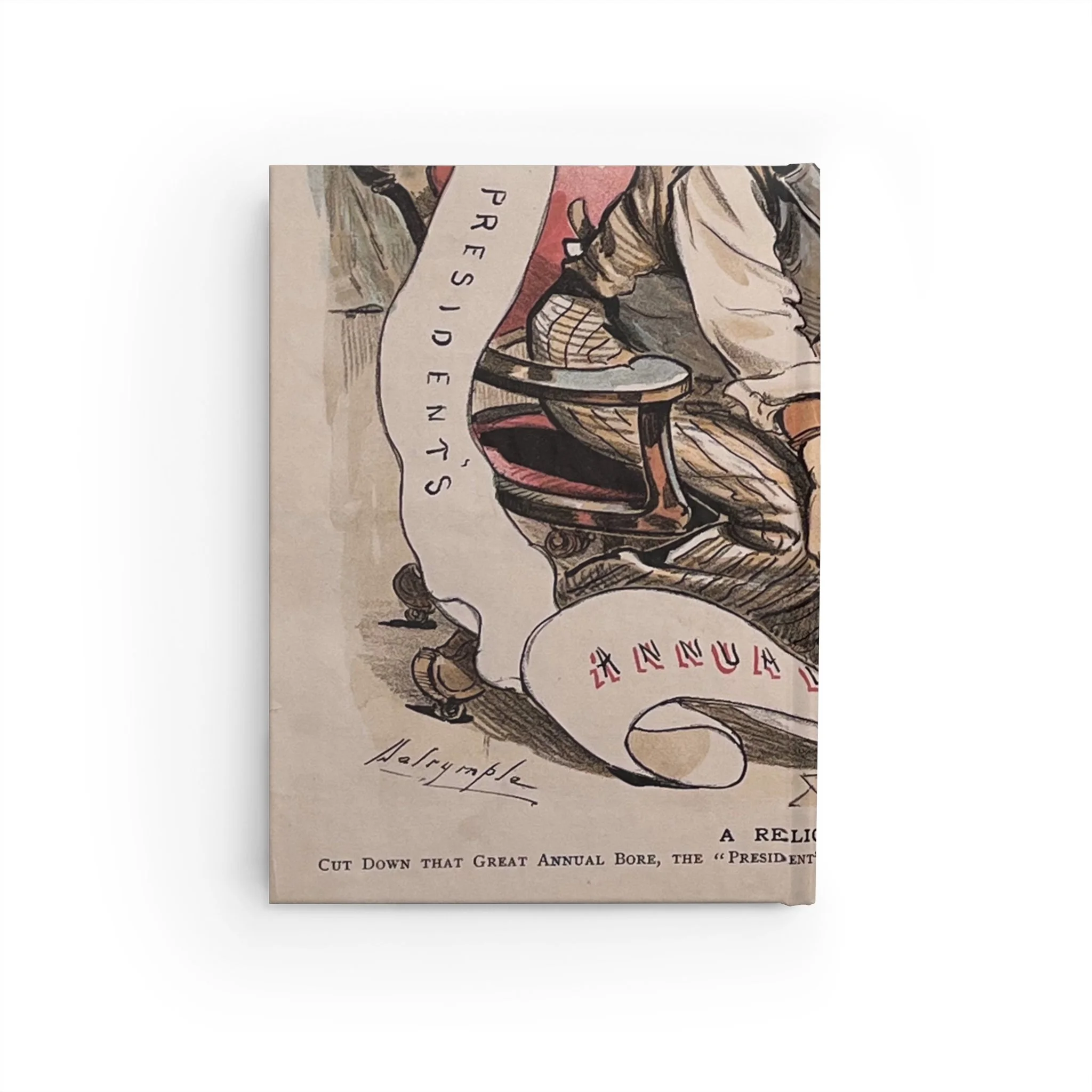

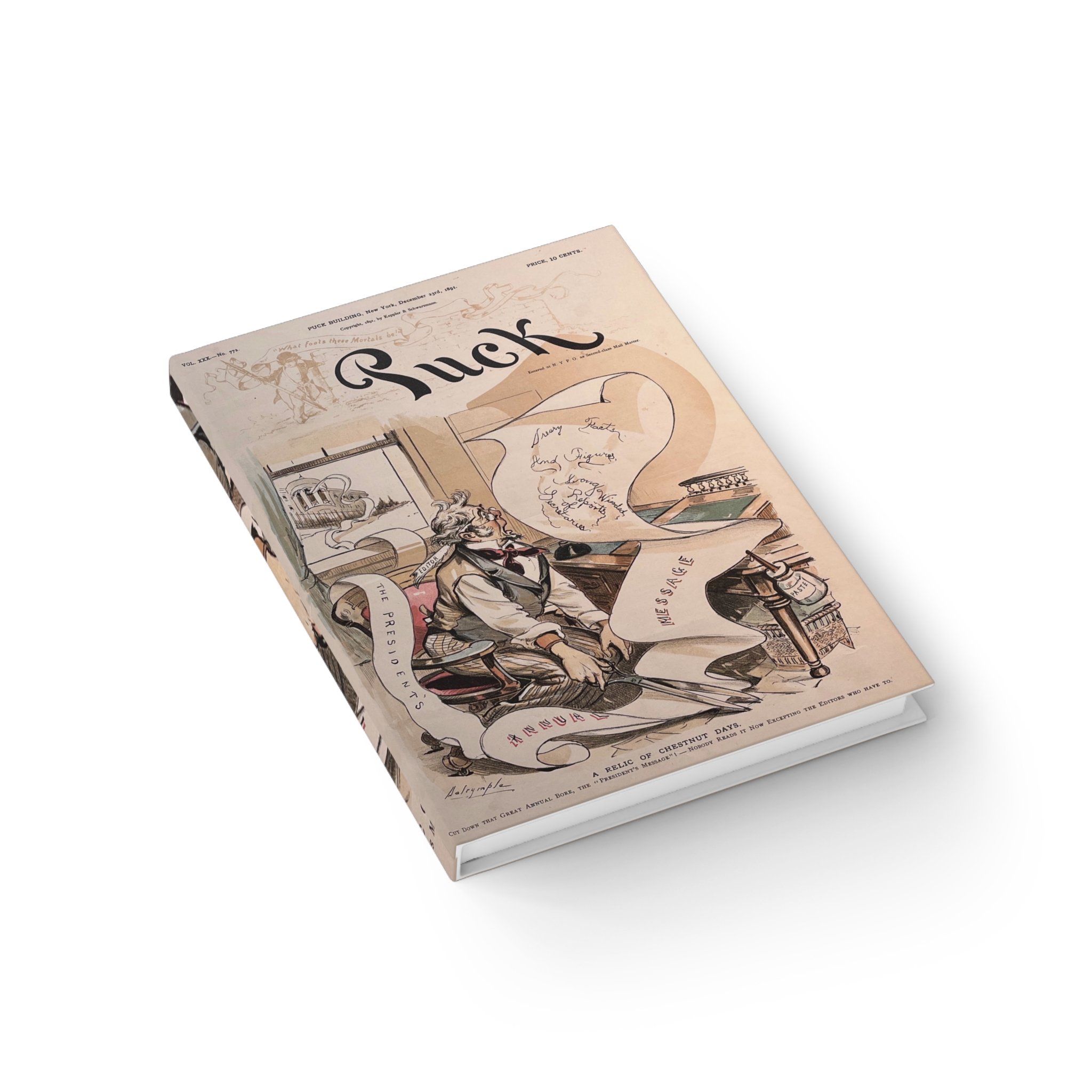

Satire aimed at political verbosity and the fatigue of endless official communication.

The image frames public discourse as an exercise in endurance, where excessive detail and ritualized language overwhelm meaning. Authority speaks at length while comprehension erodes, leaving intermediaries and audiences alike burdened by volume rather than informed by substance.

Historical Note

This cover was published in Puck magazine on December 23, 1891, and was illustrated by Louis M. Dalrymple, whose work often critiqued bureaucracy, political excess, and the performative rituals of public authority.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

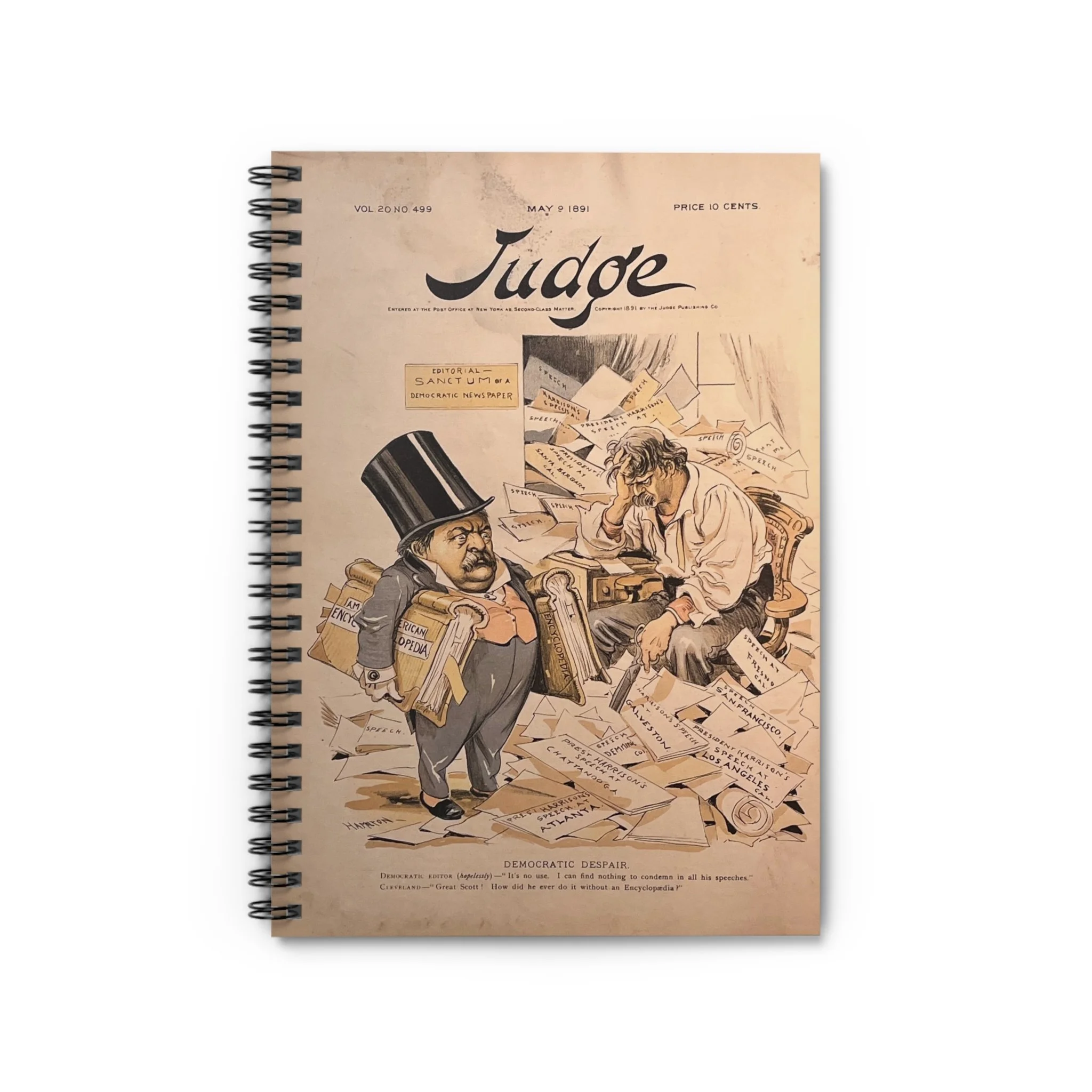

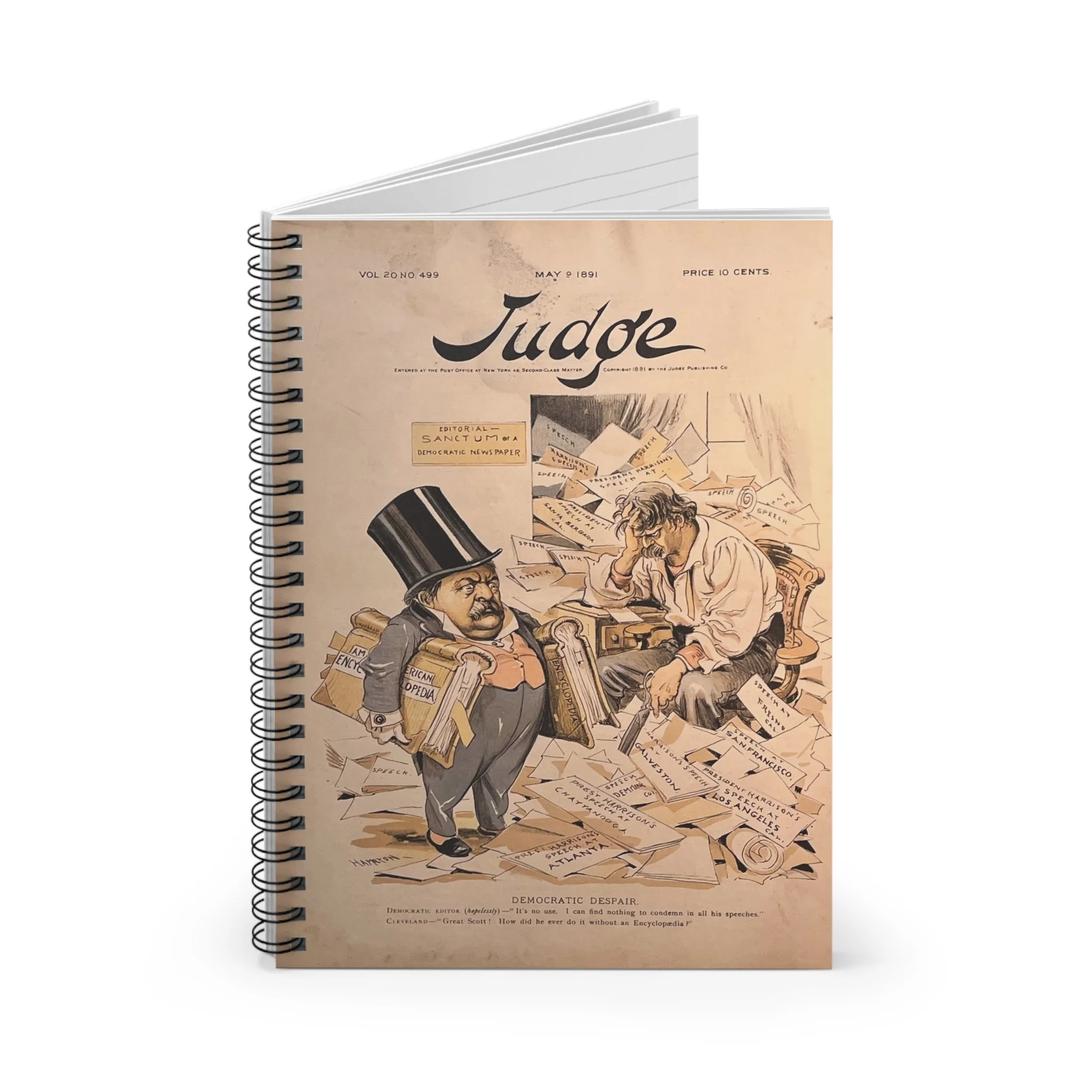

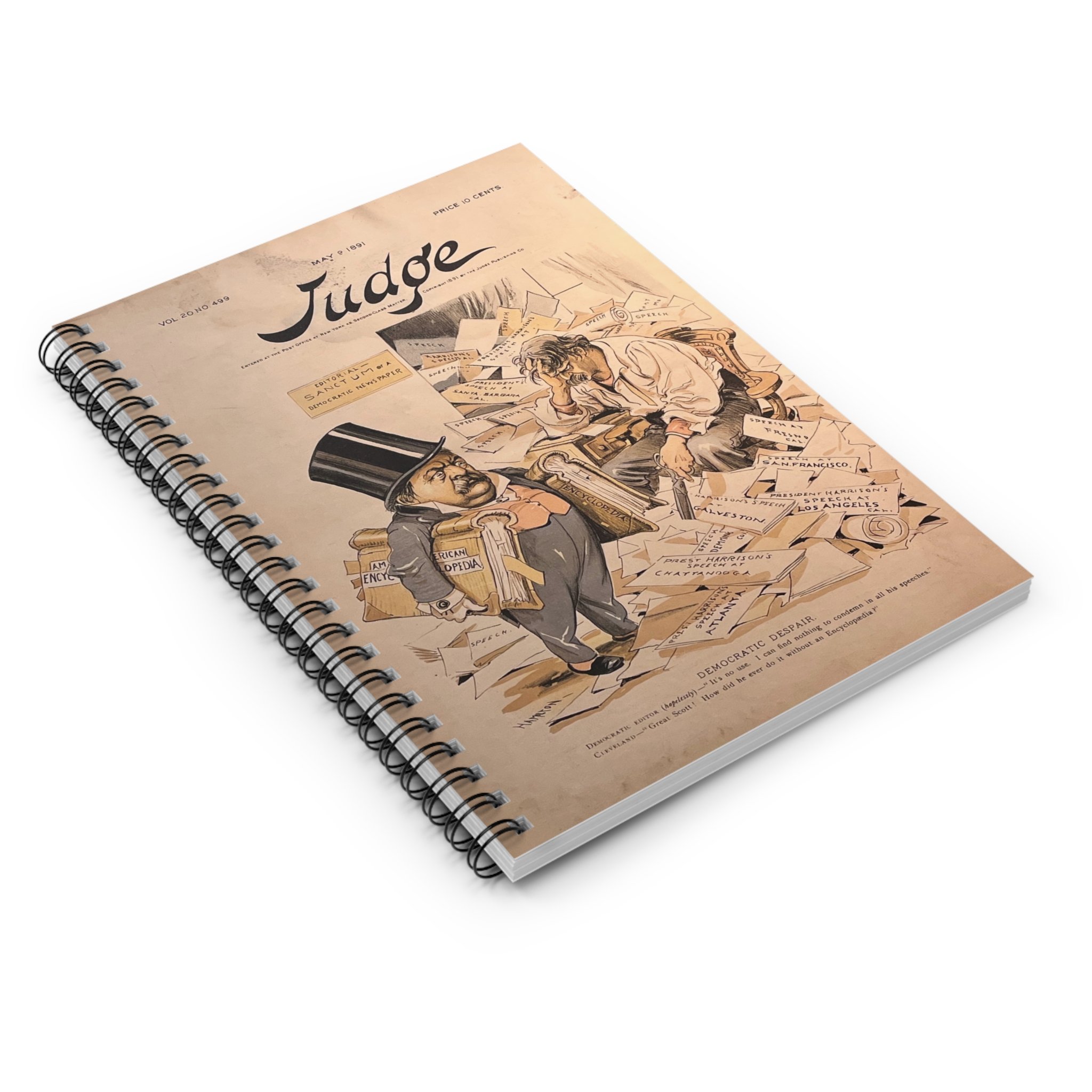

A depiction of information overload and the exhaustion of political mediation.

The image presents public discourse as an unrelenting stream of repetition and volume, where meaning is buried under accumulation rather than clarified through argument. Political communication appears industrial and scripted, leaving those tasked with interpretation strained by excess rather than guided by insight.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was drawn by Grant E. Hamilton, whose work frequently depicted the strain placed on journalists and editors by late-nineteenth-century campaign culture and partisan messaging.

6 × 8 in | Metal spiral binding | Ruled | Interior document pocket

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

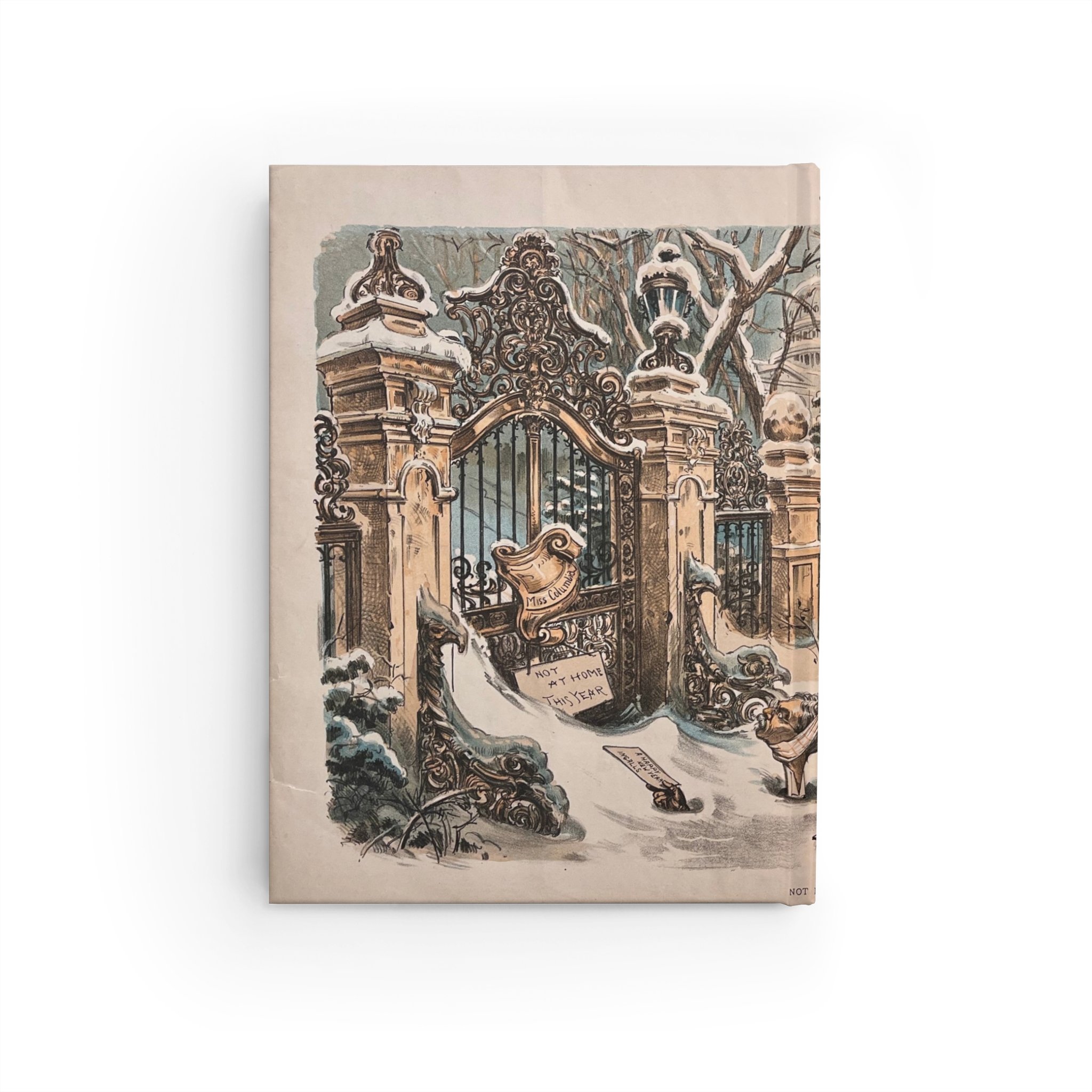

A depiction of exclusion, entitlement, and the limits of access.

The image frames public authority as something withheld rather than granted, where expectation collides with refusal. Privilege is shown lining up out of habit, only to be turned away—suggesting that legitimacy depends on restraint as much as admission.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam. It satirizes political insiders who assumed automatic access to power, using the closed gate as a metaphor for democratic boundaries.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Blank | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

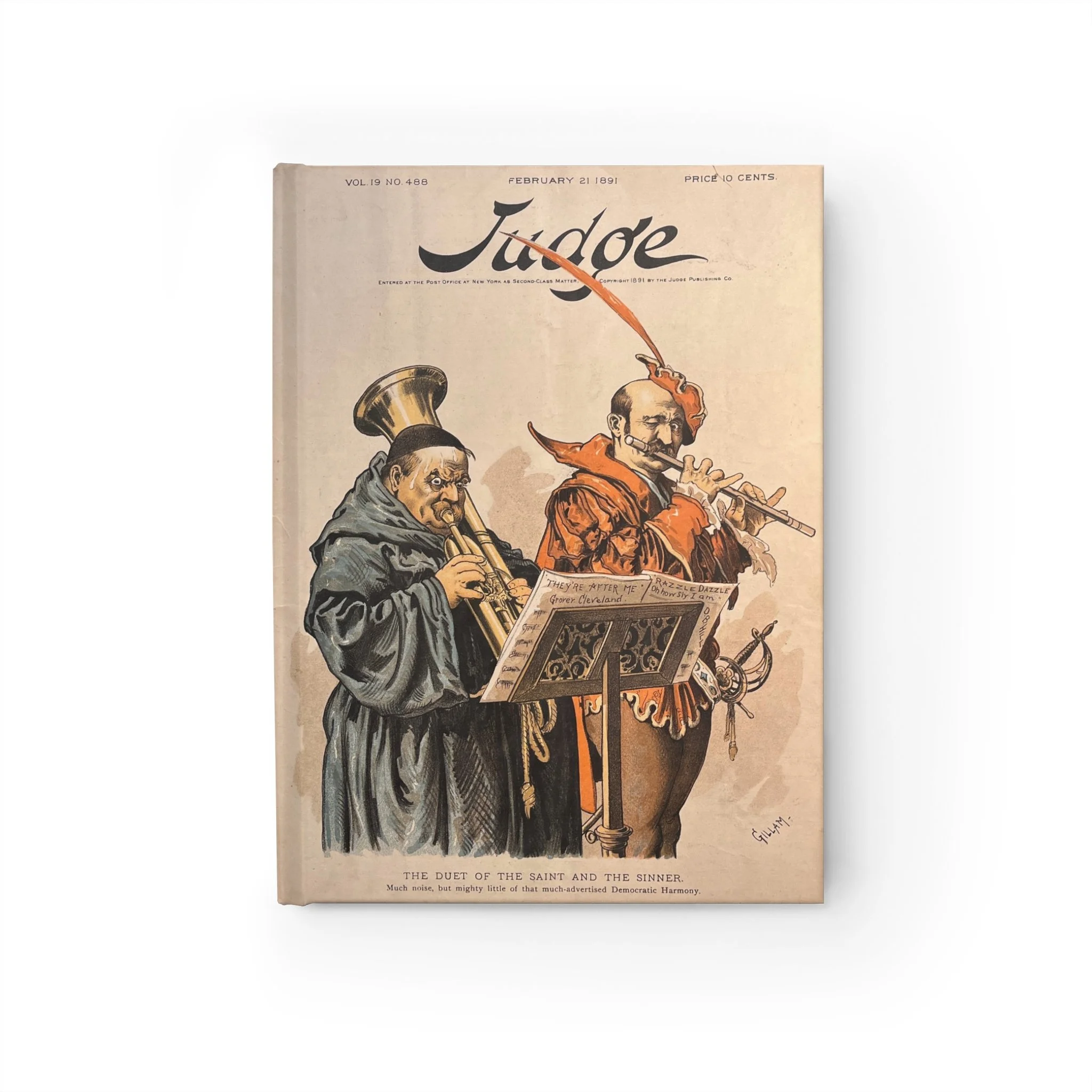

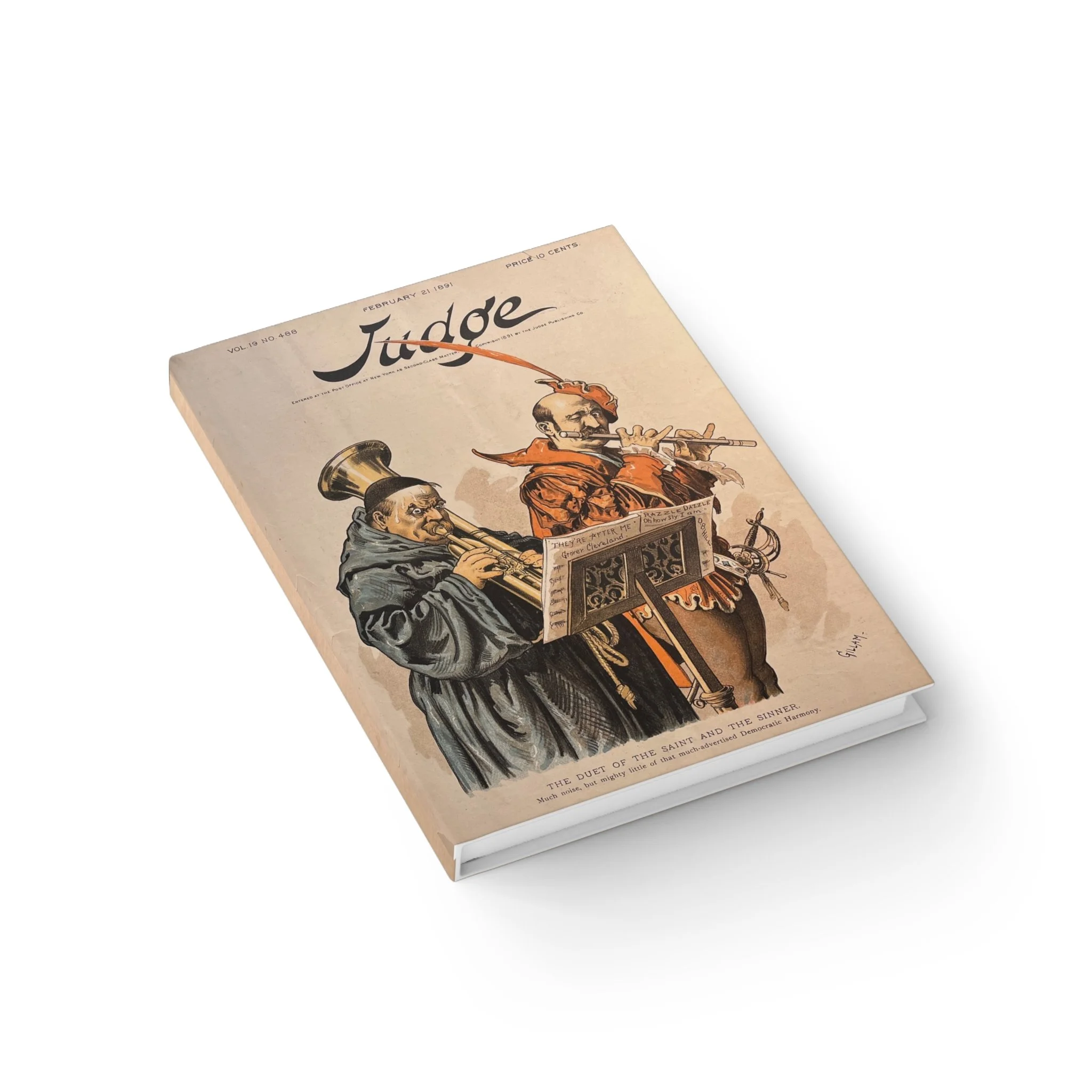

Satire depicting performative unity and the spectacle of incompatible alliance.

The image presents agreement as something staged rather than achieved, where moral opposites are placed side by side and declared harmonious by fiat. Cooperation appears theatrical and unstable, suggesting that proclaimed unity can mask deeper incoherence rather than resolve it.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Bernhard Gillam. Titled “The Duet of the Saint and the Sinner,” it uses visual contrast to critique political alliances that announce harmony while exposing fundamental contradiction.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

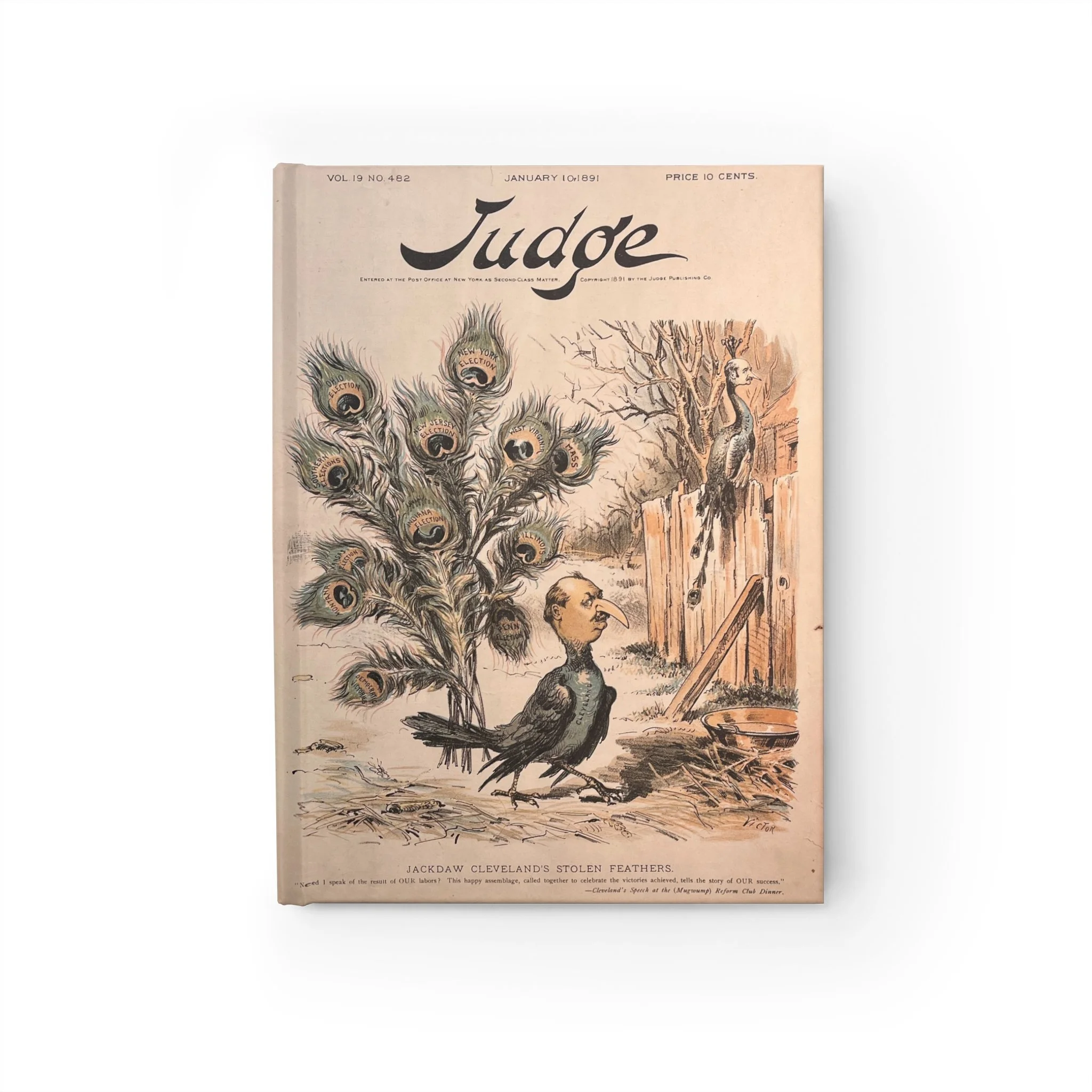

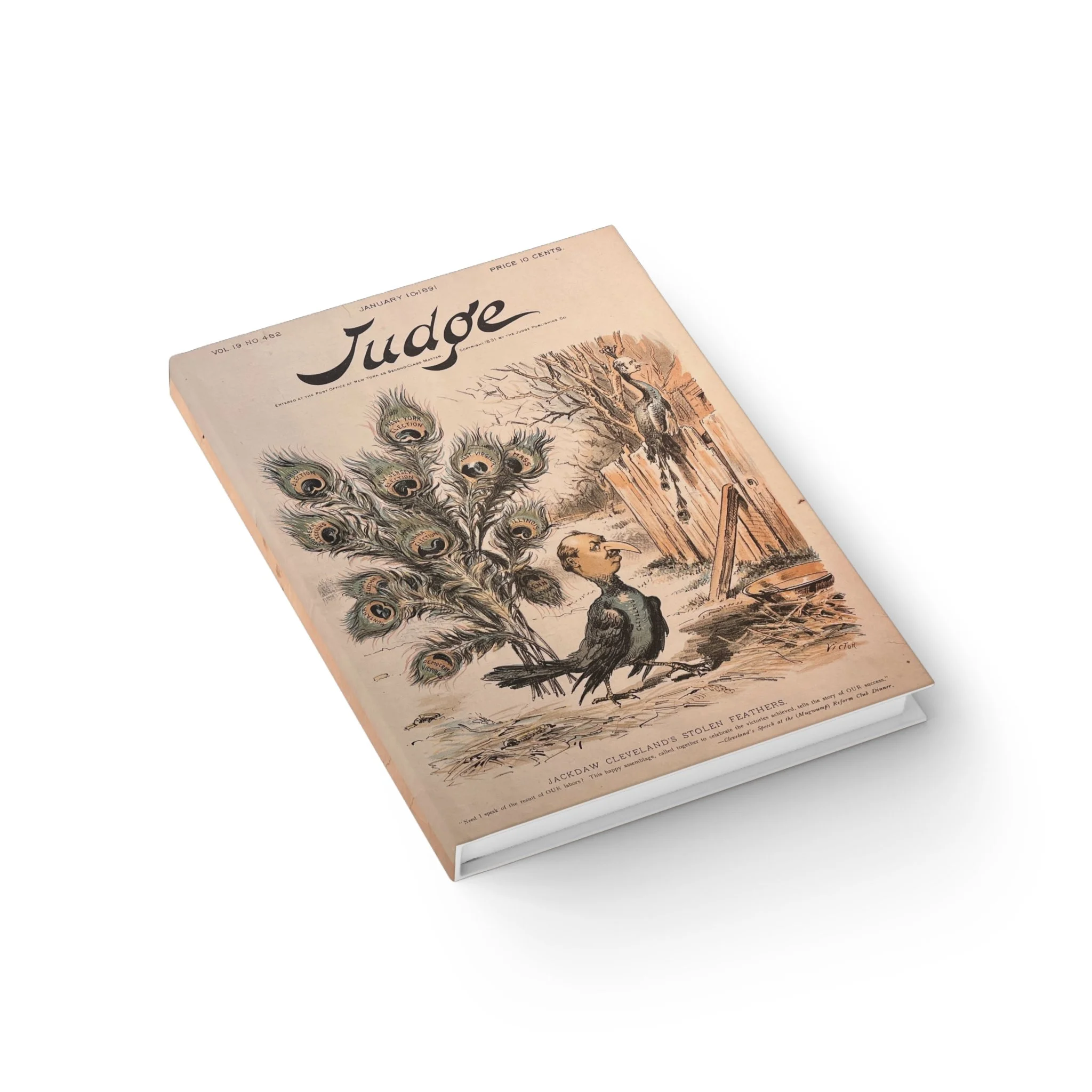

A satirical critique of political appropriation and manufactured success.

The image presents public ambition as a performance built on display rather than achievement. Authority is shown claiming outcomes it did not earn, relying on spectacle and repetition to convert loss into the appearance of victory. Power, here, is less about results than about who controls the narrative.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in an 1891 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Victor Gillam. It uses visual parody to critique political figures who claim credit through exaggeration, display, and rhetorical sleight of hand rather than electoral fact.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Blank | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

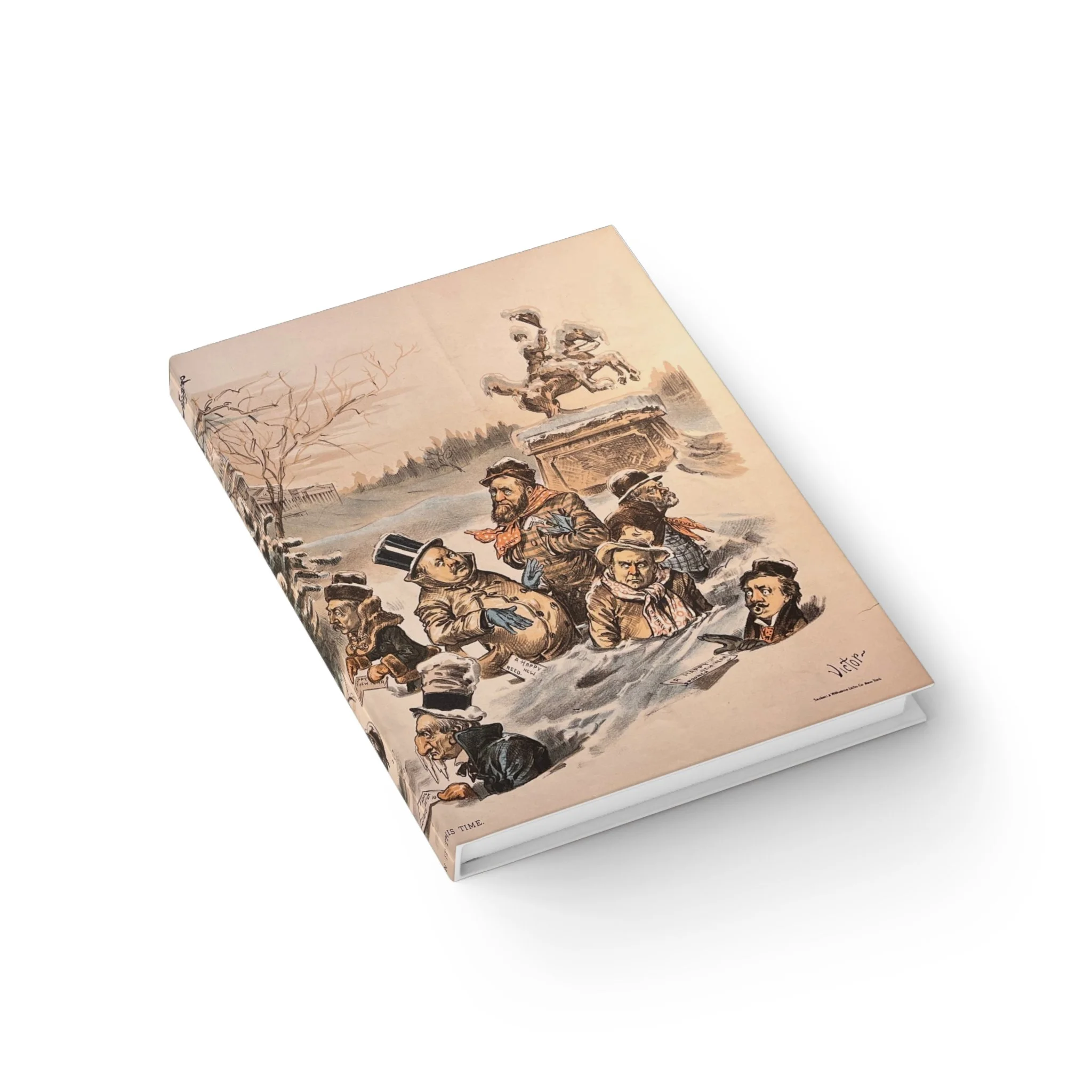

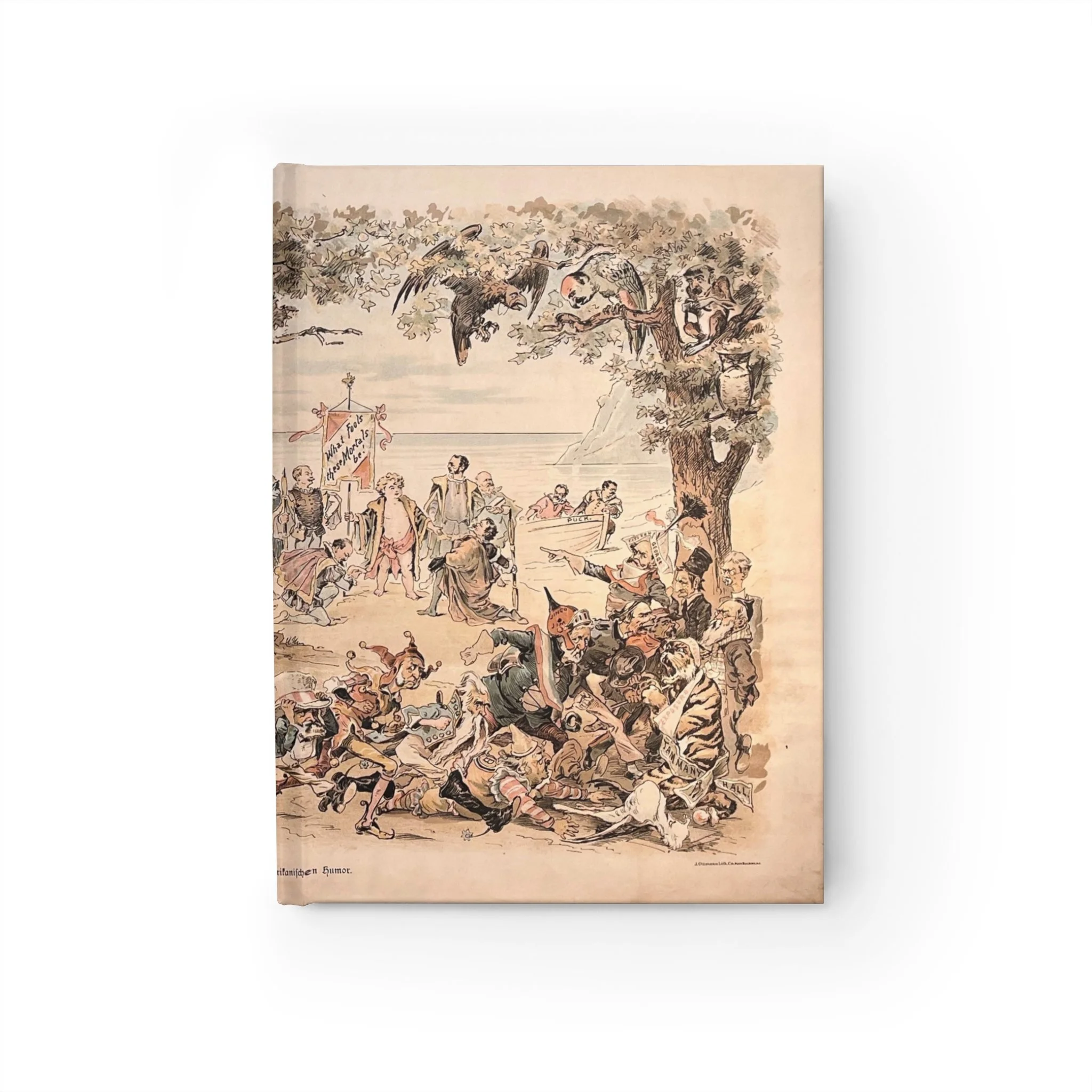

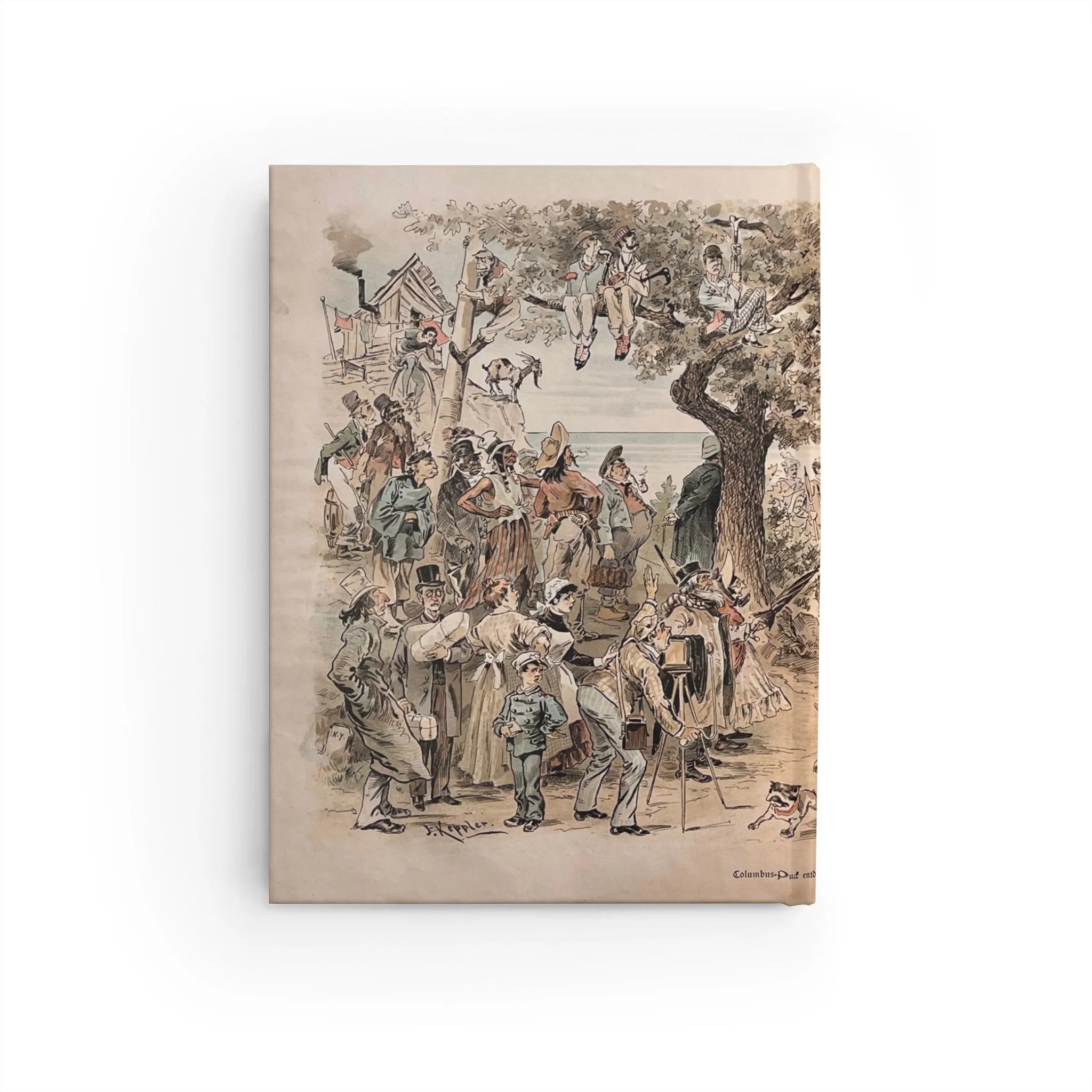

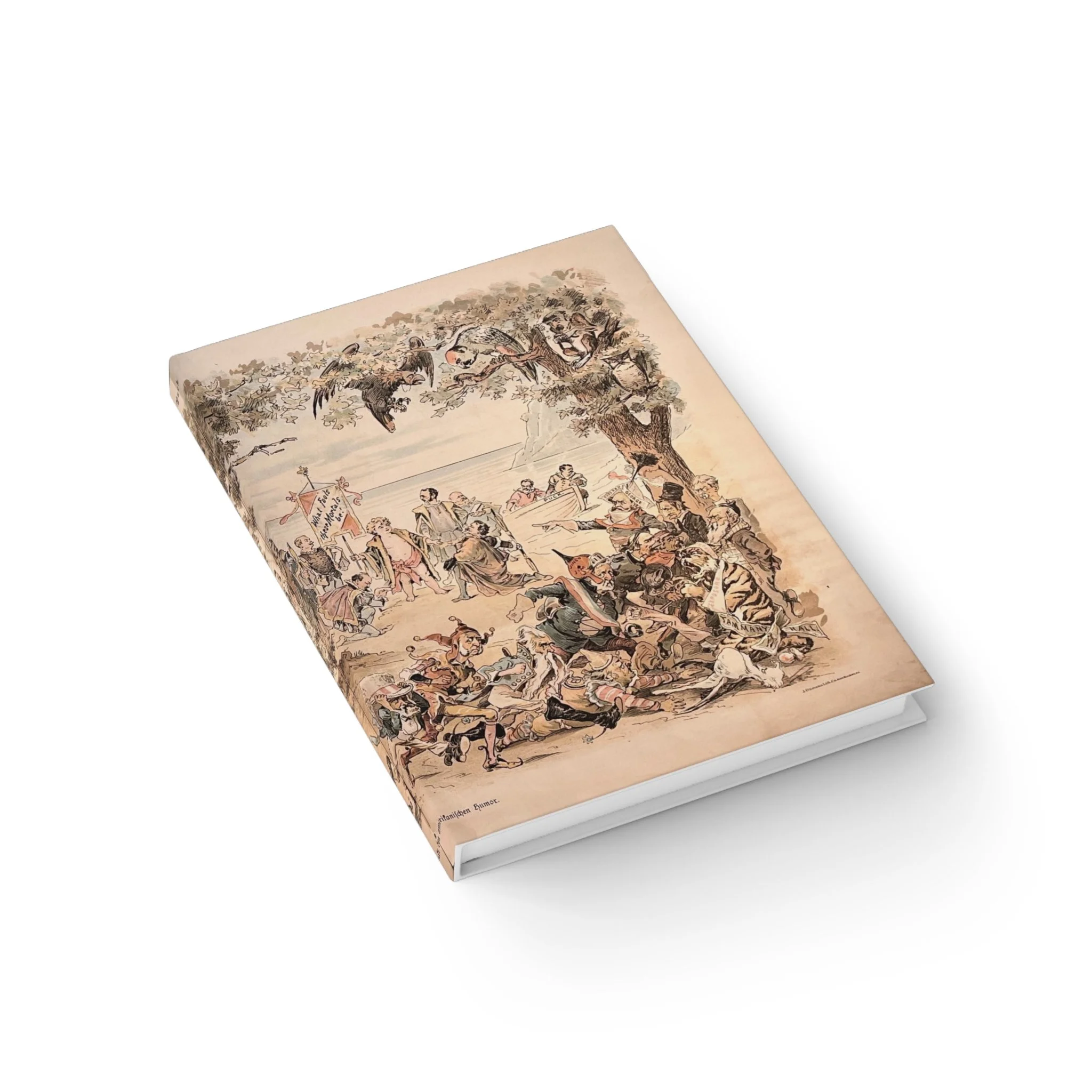

A study of mass participation, public performance, and the instability of collective enthusiasm.

The image presents civic life as a crowded stage, where ambition, humor, and tension coexist without clear hierarchy. Public energy appears expansive and animated, yet precarious—suggesting that national identity is formed as much through spectacle and proximity as through order or consensus.

Historical Note

This two-page illustration appeared in an early 1890s issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Joseph Keppler. Known for large ensemble scenes, Keppler used dense composition to explore the performance of power, social diversity, and the contradictions of American public life.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Blank | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

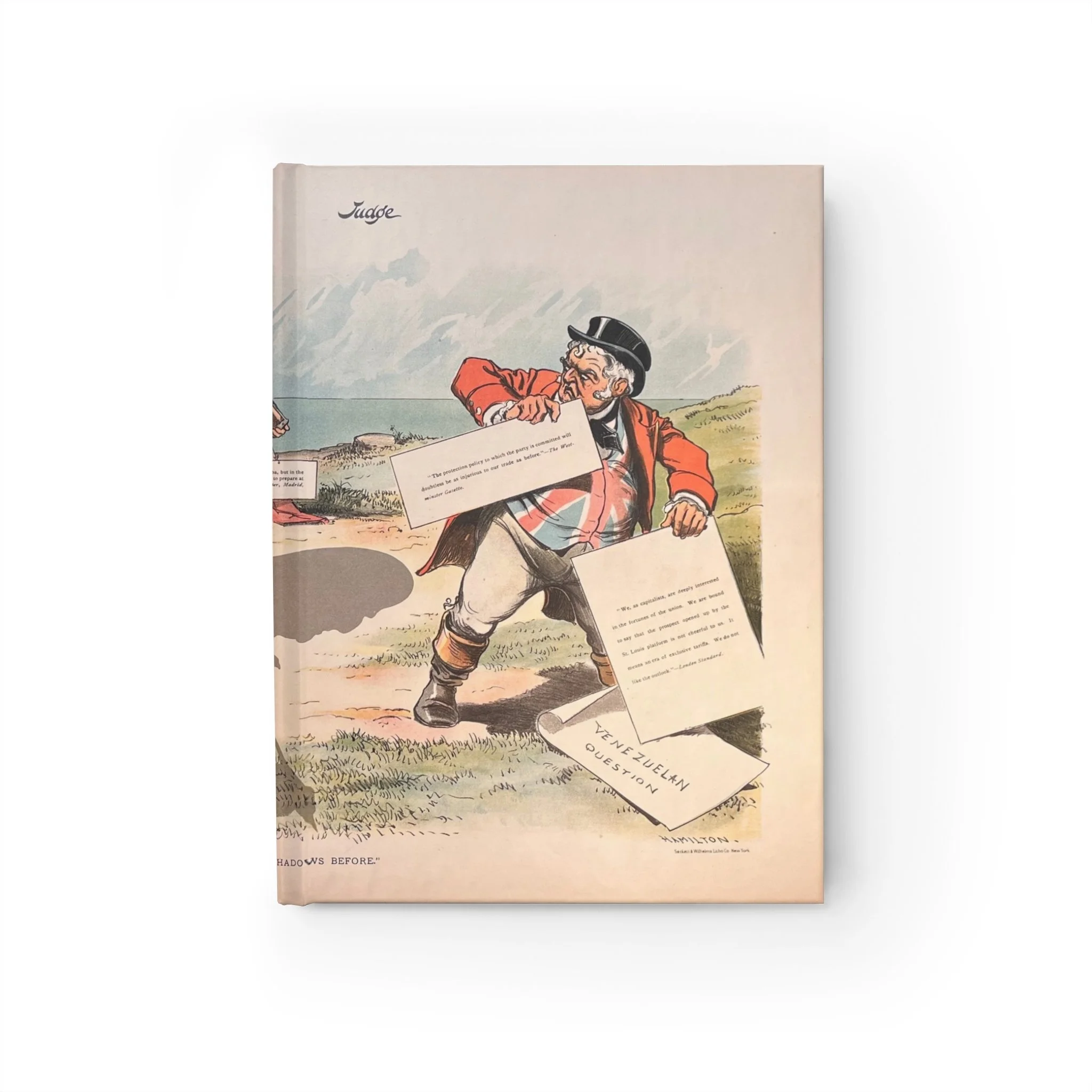

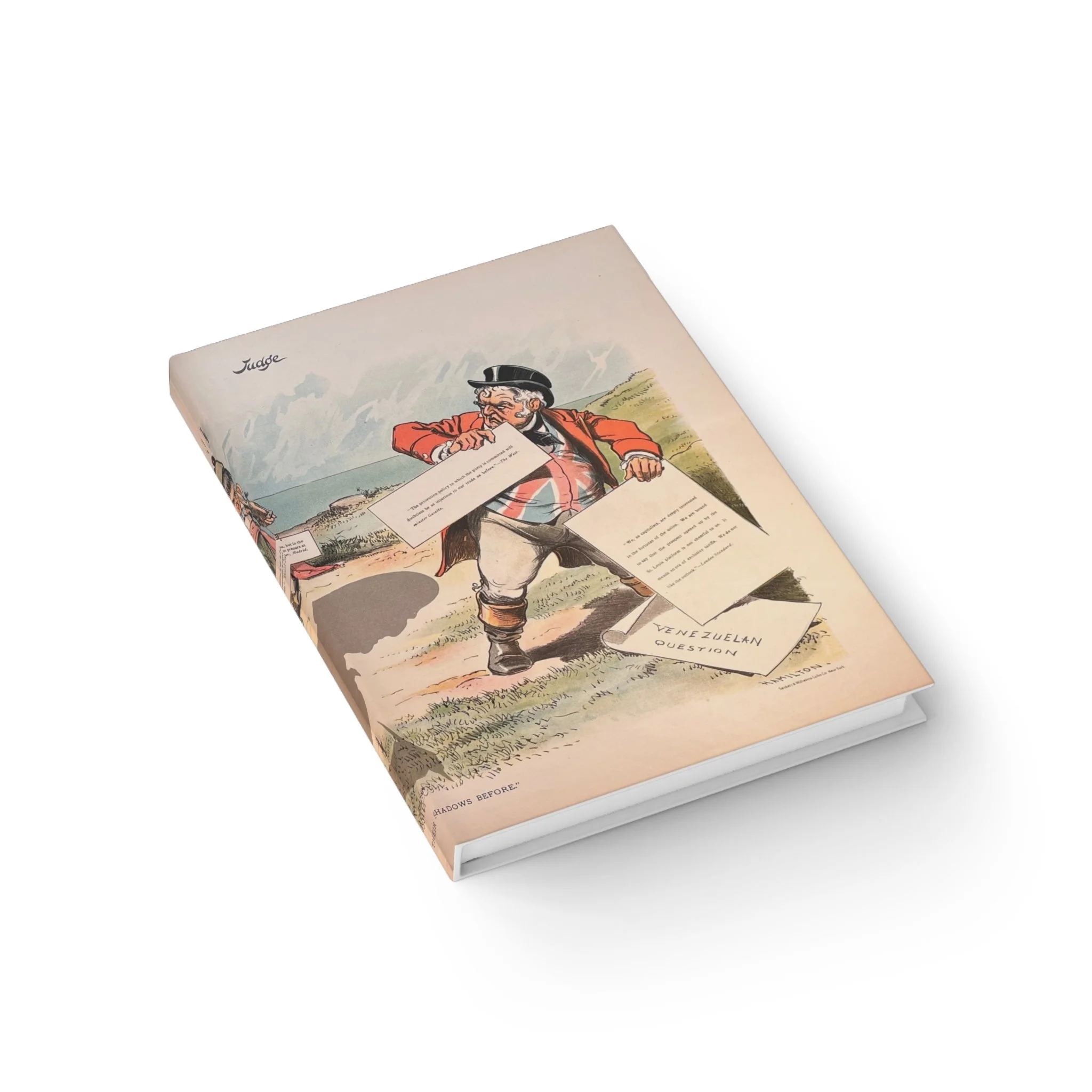

A satirical critique of expansionist ambition and the use of language as a substitute for restraint.

The image portrays power advancing through declarations rather than force, suggesting that imperial consequences often take shape before conflict formally begins. Authority appears confident in speech while shadowed by outcomes already set in motion, exposing the gap between proclamation and responsibility.

Historical Note

This large-format cartoon appeared in a July 1896 issue of Judge magazine and was illustrated by Grant E. Hamilton. Responding to the Venezuelan Question, it reflects late-nineteenth-century American satire skeptical of imperial rhetoric and the justifications used to normalize expansion.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

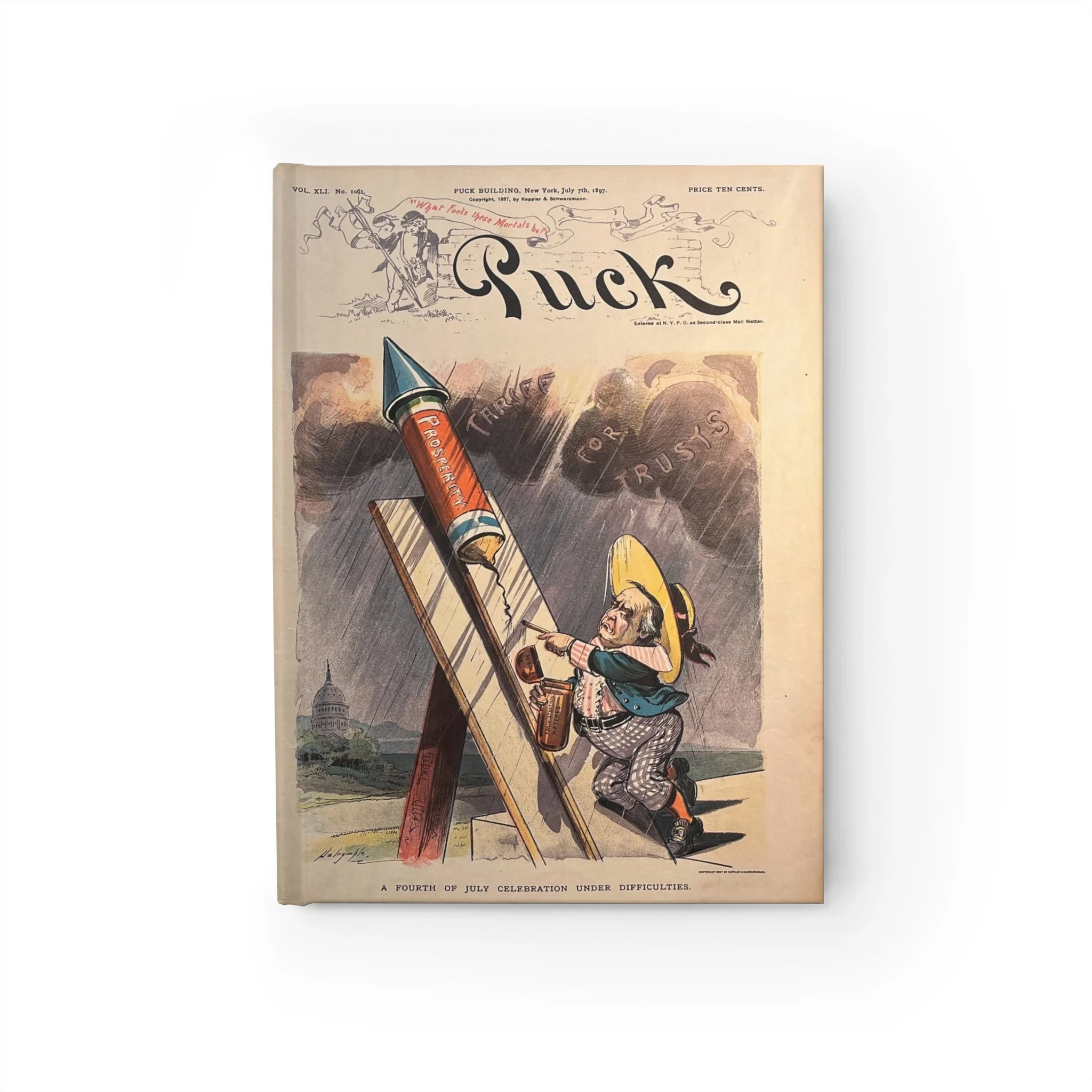

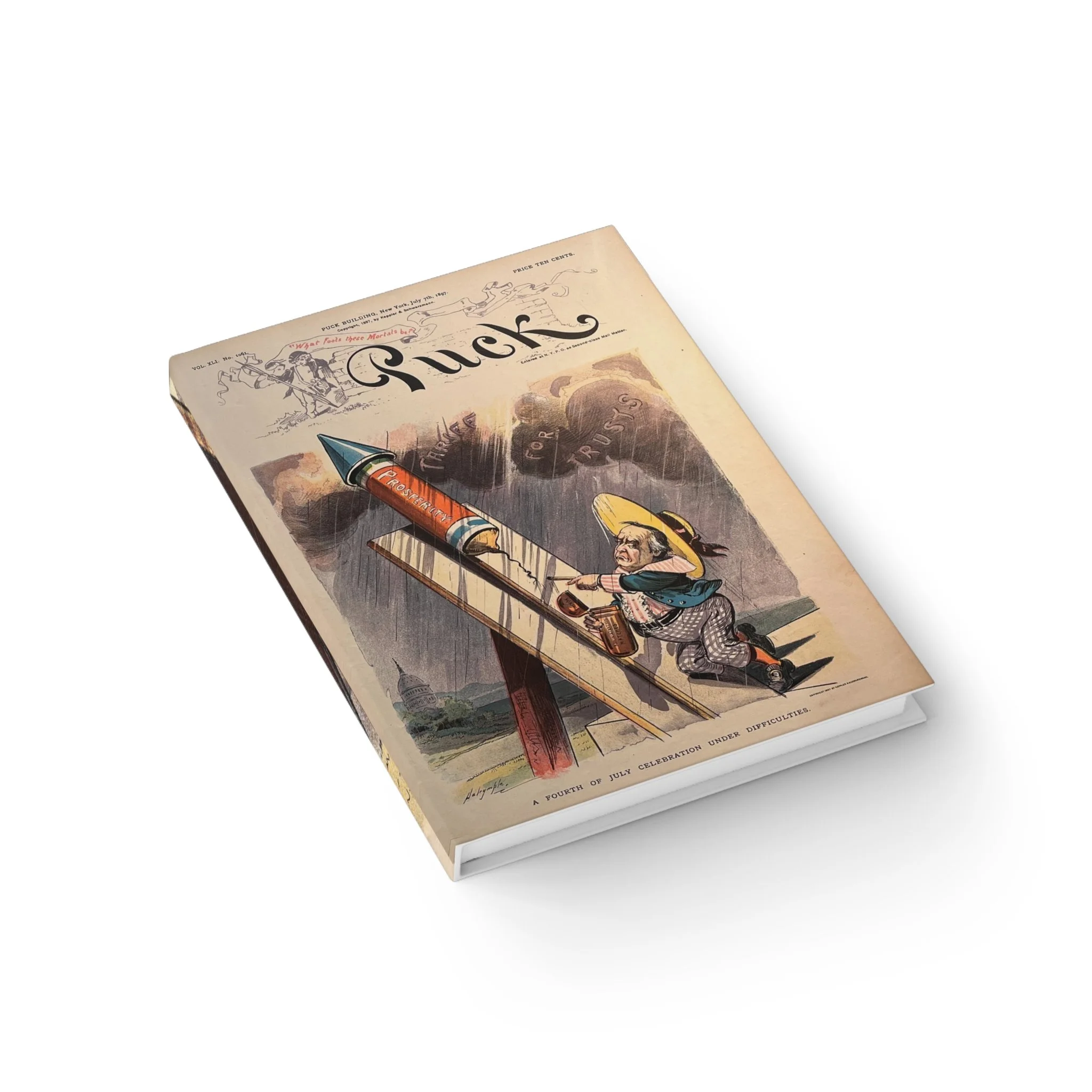

Satire aimed at hollow celebration and the weight of policy on public optimism.

The image presents national pride as a stalled ritual, where promised prosperity struggles to take flight under accumulating constraints. Confidence is shown as ceremonial rather than realized, suggesting that economic policy can dampen collective momentum even in moments meant for unity and renewal.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in an 1897 issue of Puck magazine and was illustrated by Louis M. Dalrymple. It critiques the impact of protectionist policy and concentrated economic power on public life, using patriotic imagery to underscore political strain.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

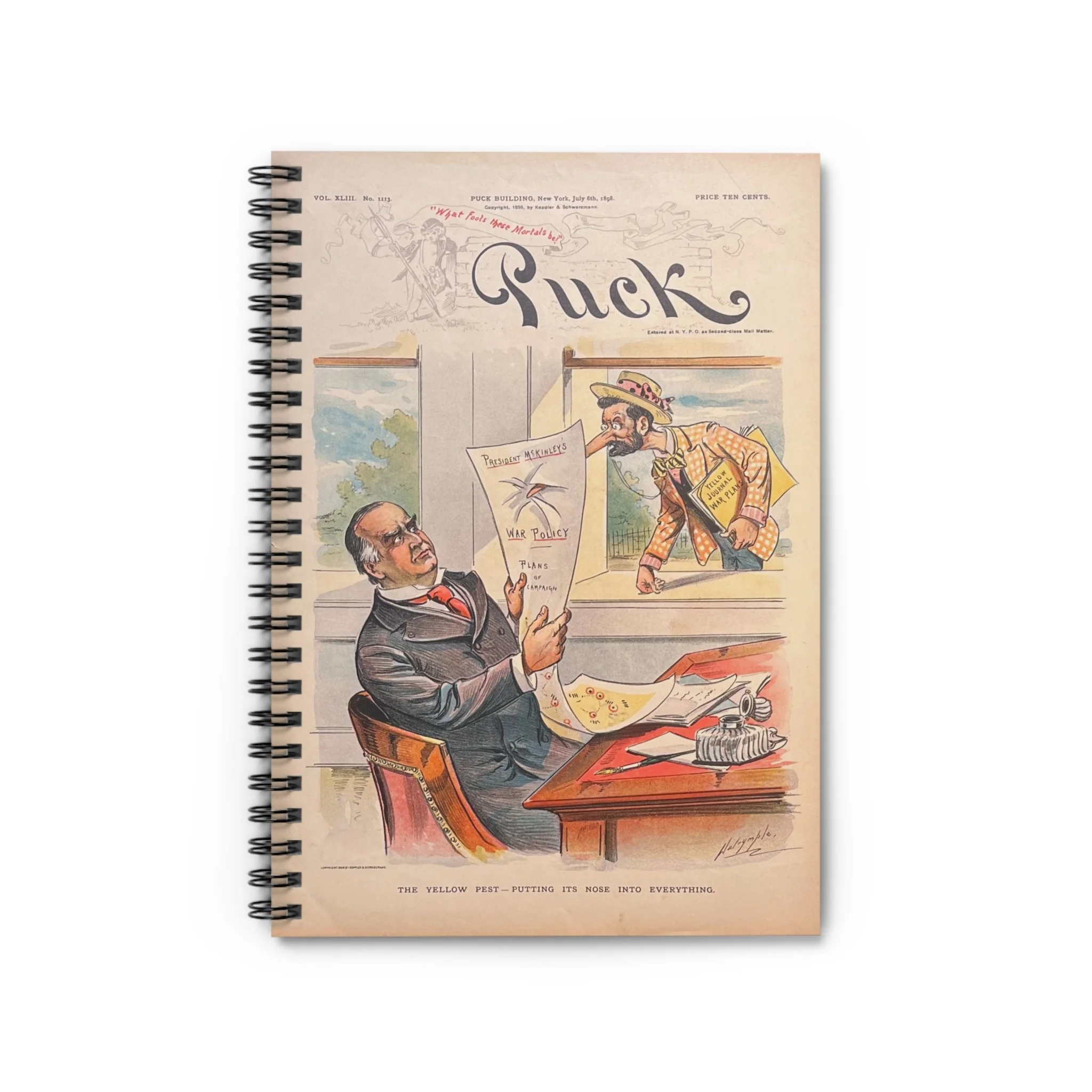

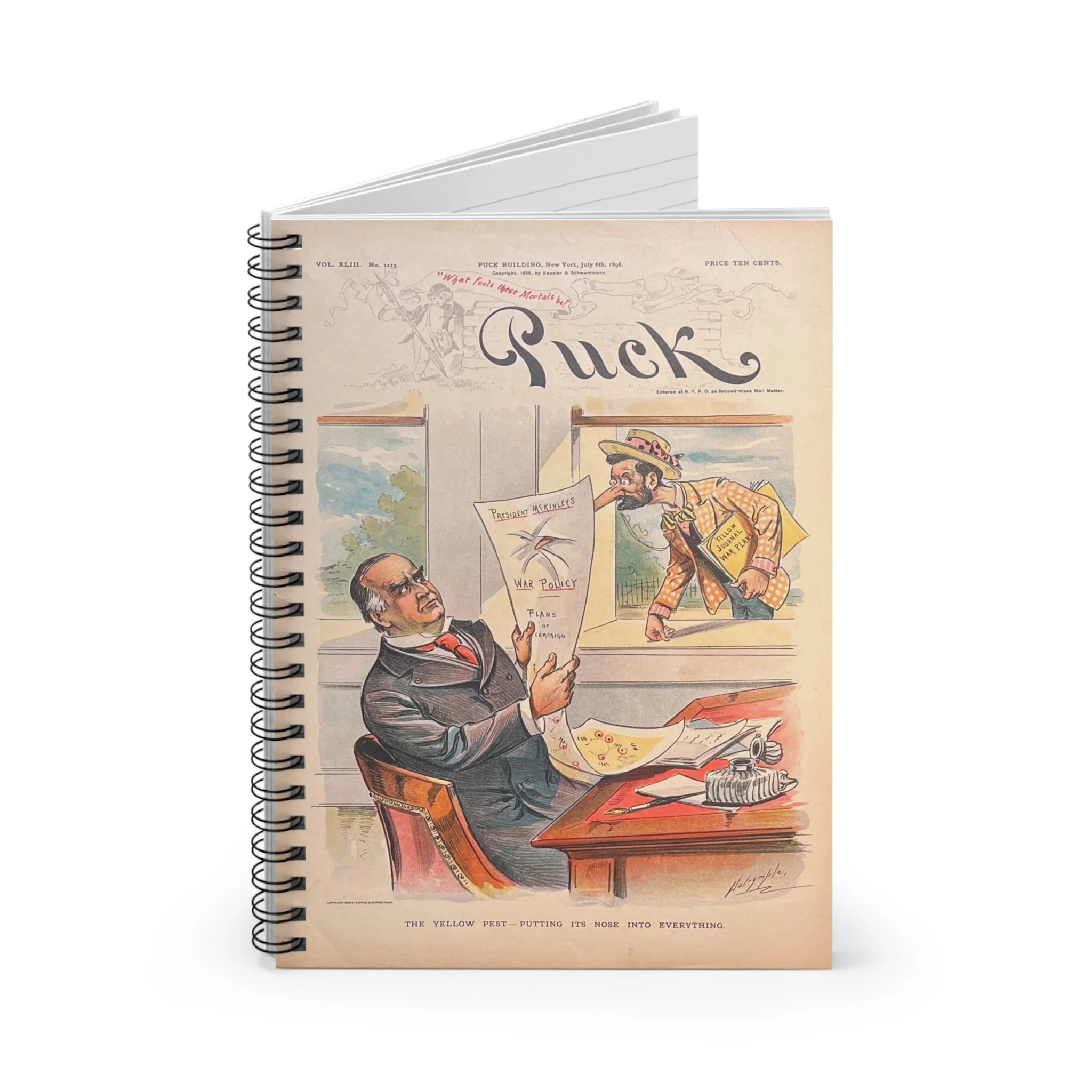

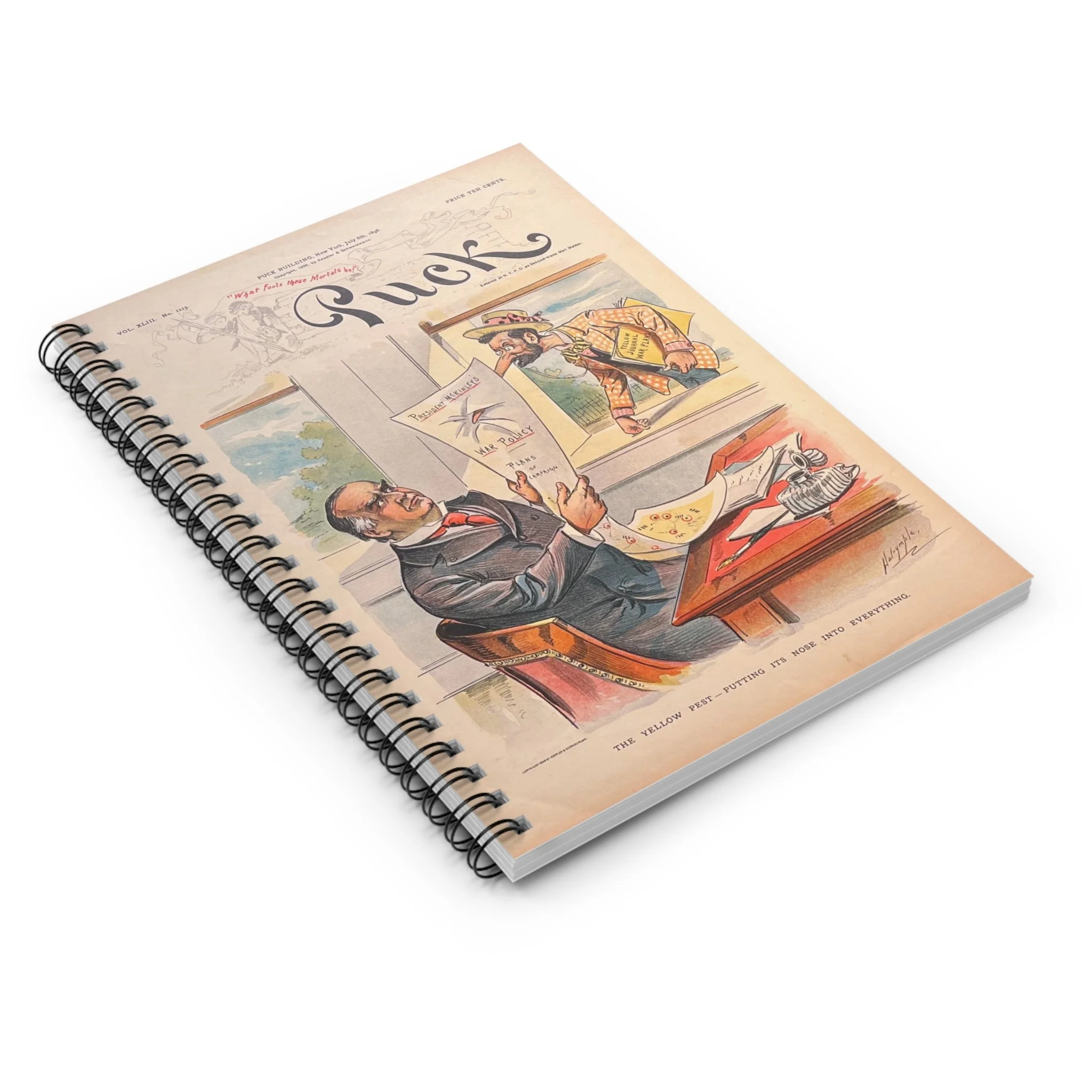

Satire of sensationalism, manufactured outrage, and the intrusion of spectacle into governance.

The image frames public decision-making as vulnerable to external pressure, where urgency is amplified through display rather than deliberation. Authority appears encroached upon by noise posing as necessity, suggesting how spectacle can displace restraint at moments of consequence.

Historical Note

This cartoon was published in an 1898 issue of Puck magazine during the Spanish–American War and was illustrated by Louis M. Dalrymple. It critiques the influence of yellow journalism on political judgment, depicting media pressure as a force that presses itself into the machinery of war.

6 × 8 in | Metal spiral binding | Ruled | Interior document pocket

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

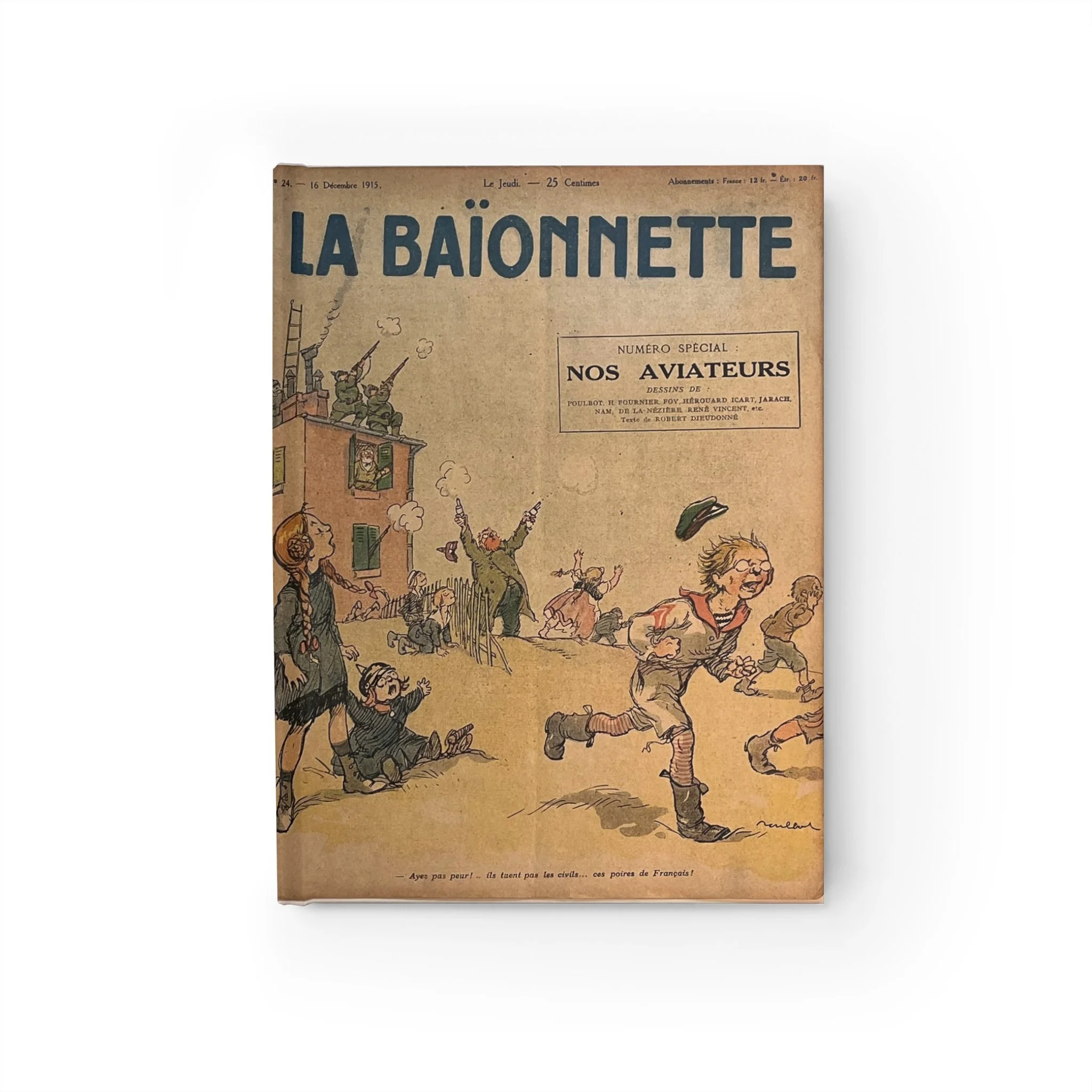

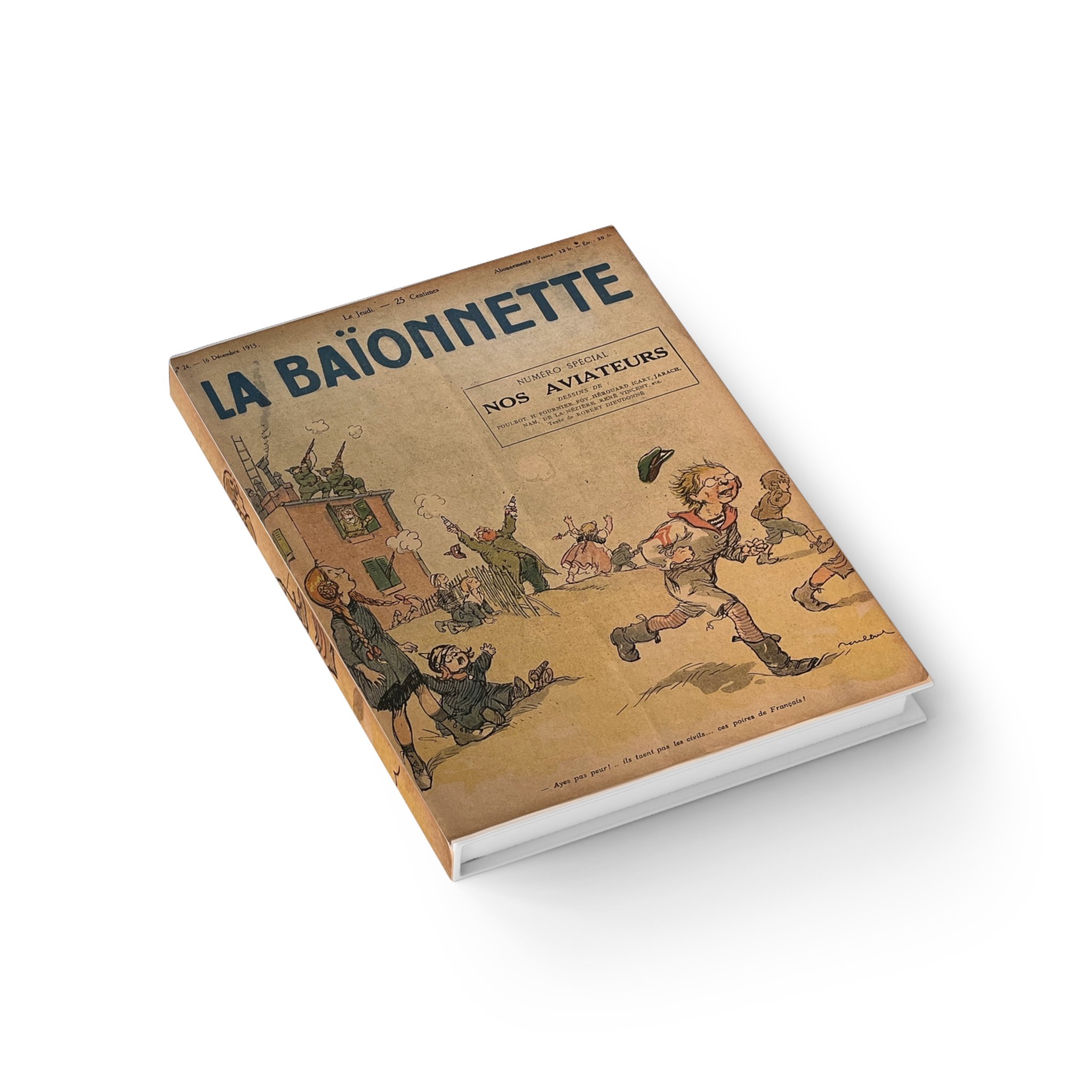

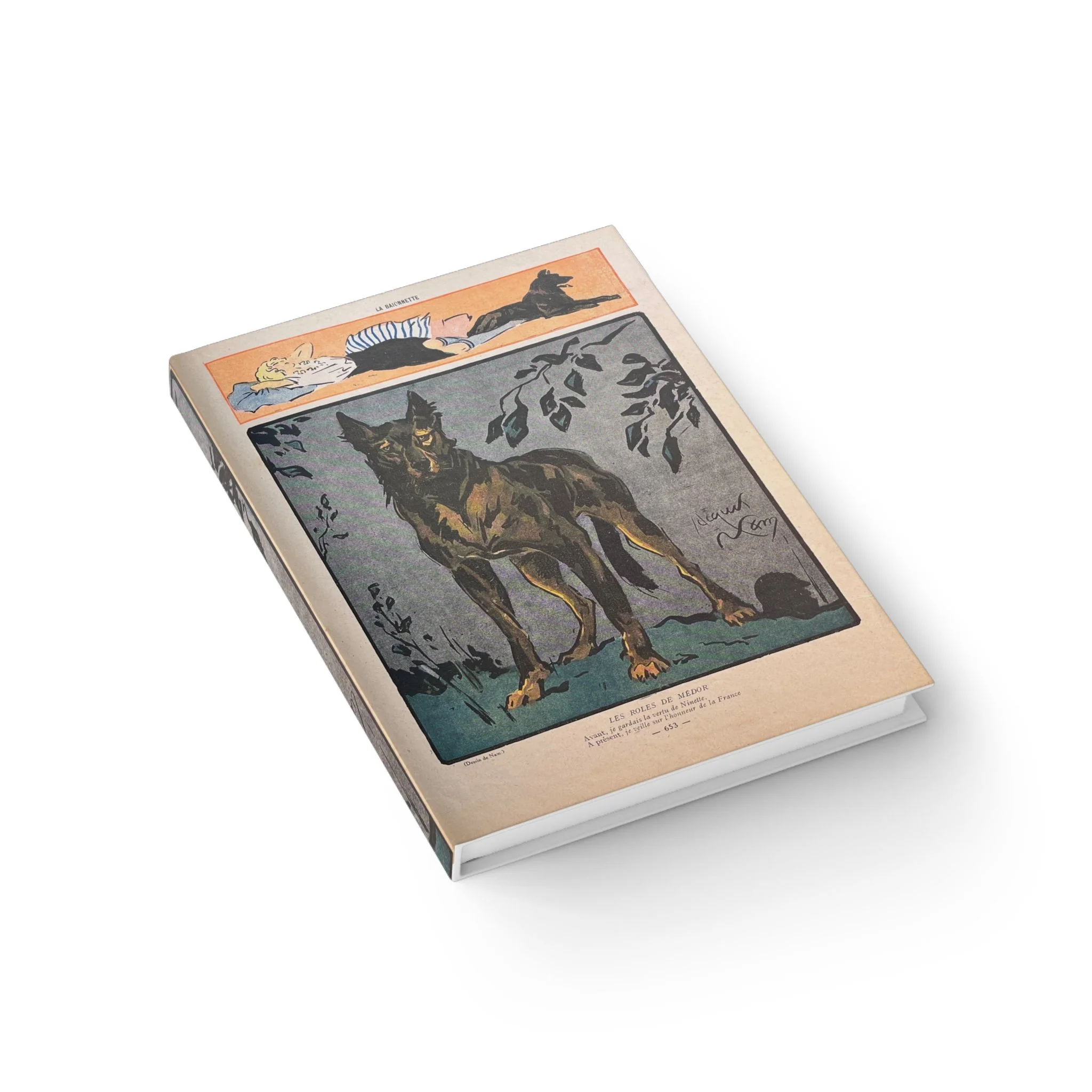

A depiction of technological warfare and the collapse of civilian protection.

The image presents modern conflict as chaotic and indiscriminate, where claims of control dissolve into panic on the ground. Reassurance is rendered hollow, exposing the distance between official language and lived consequence when violence is framed as progress.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in a 1915 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Louis Renéfer. It uses bitter irony to critique aerial warfare and the normalization of civilian exposure during the First World War.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

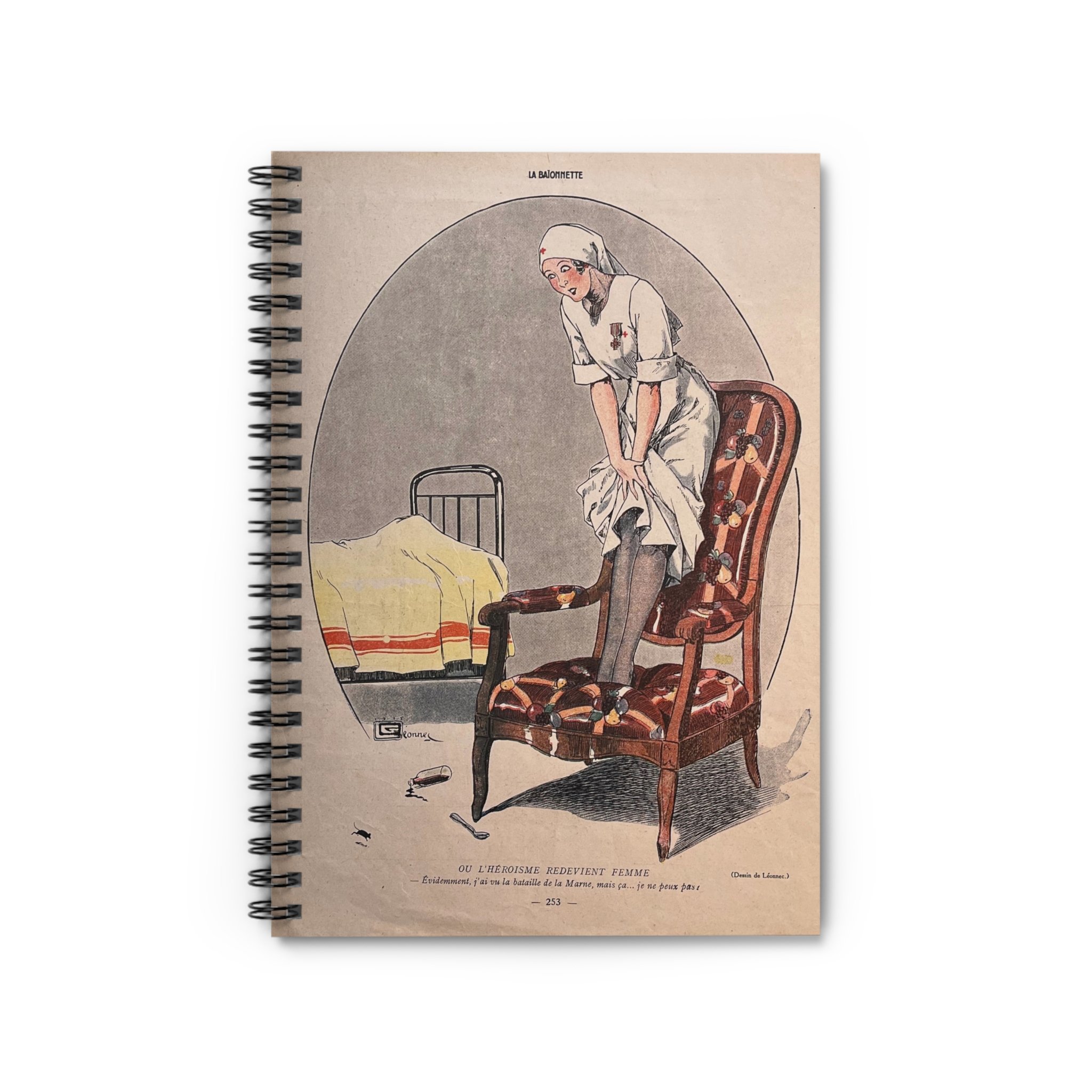

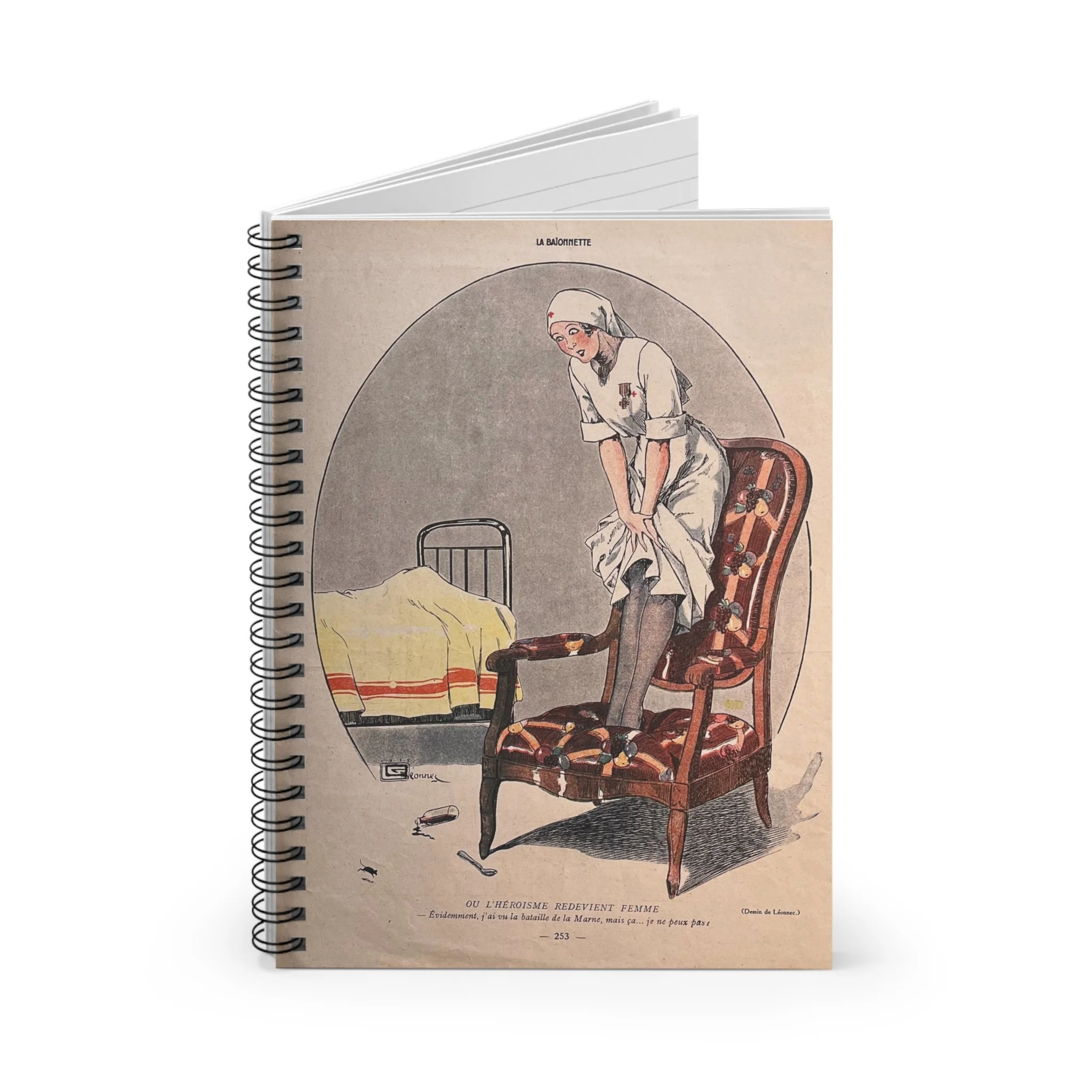

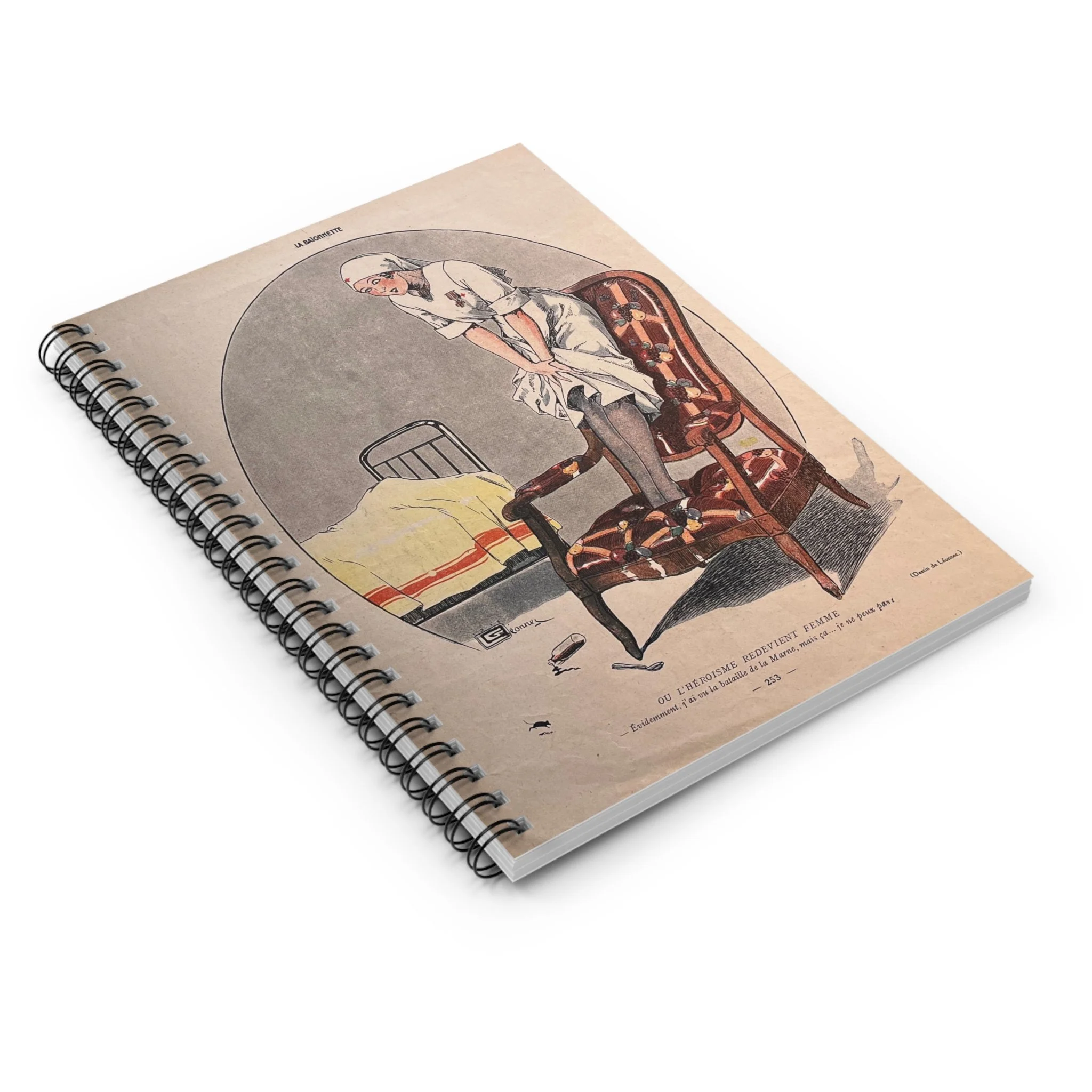

A satirical treatment of the tension between public service and private strain.

The image shifts attention from heroics to an unguarded pause, where composure and fatigue coexist. By lingering on a small, human gesture, authority and endurance are reframed as lived experience rather than spectacle, suggesting that service is sustained as much by vulnerability as by resolve.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in a 1915 issue of La Baïonnette and was drawn by Léonnec. It contrasts decorated wartime roles with everyday human fragility, using restrained humor to register the personal cost of service away from the battlefield.

6 × 8 in | Metal spiral binding | Interior document pocket | Front illustration with dark grey back cover

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

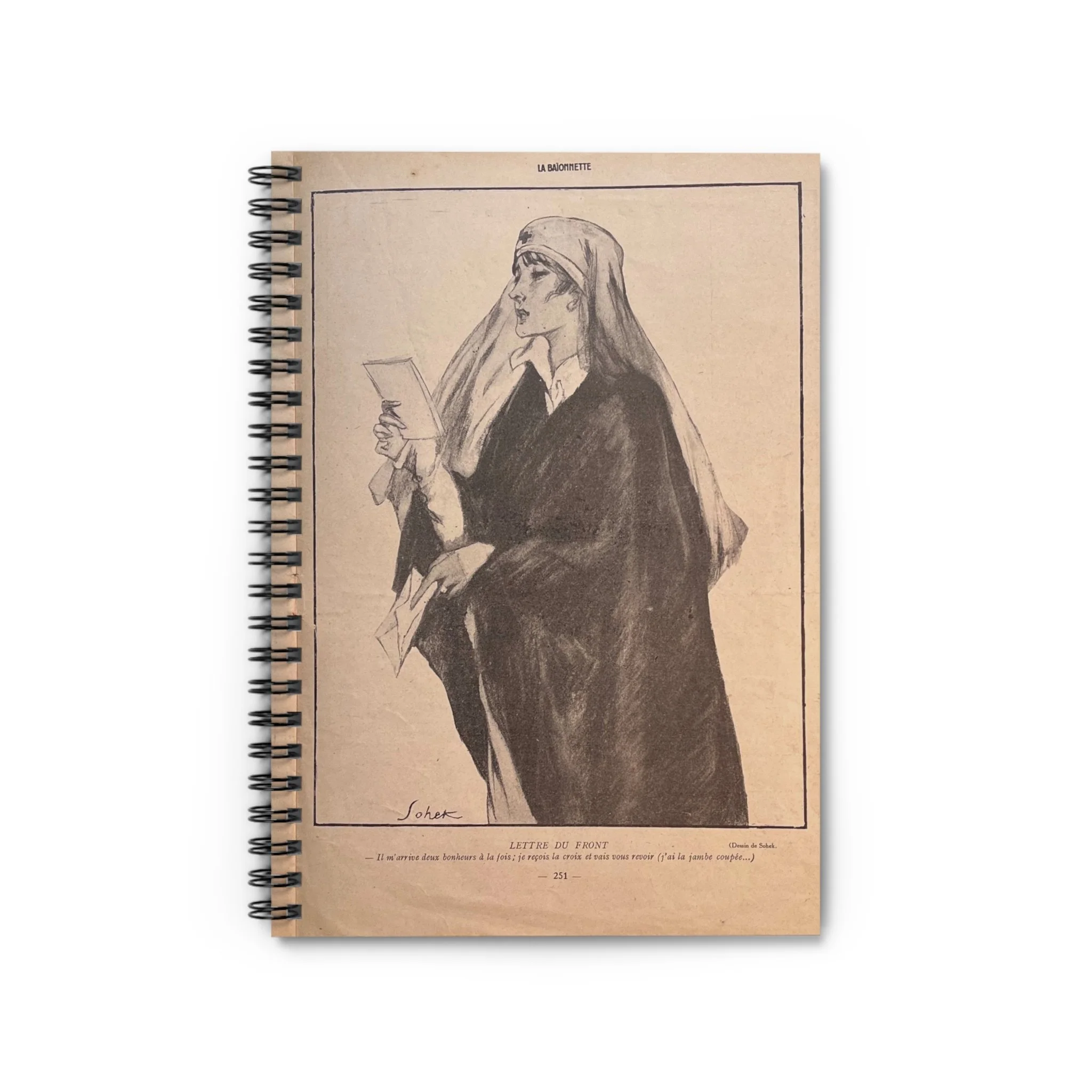

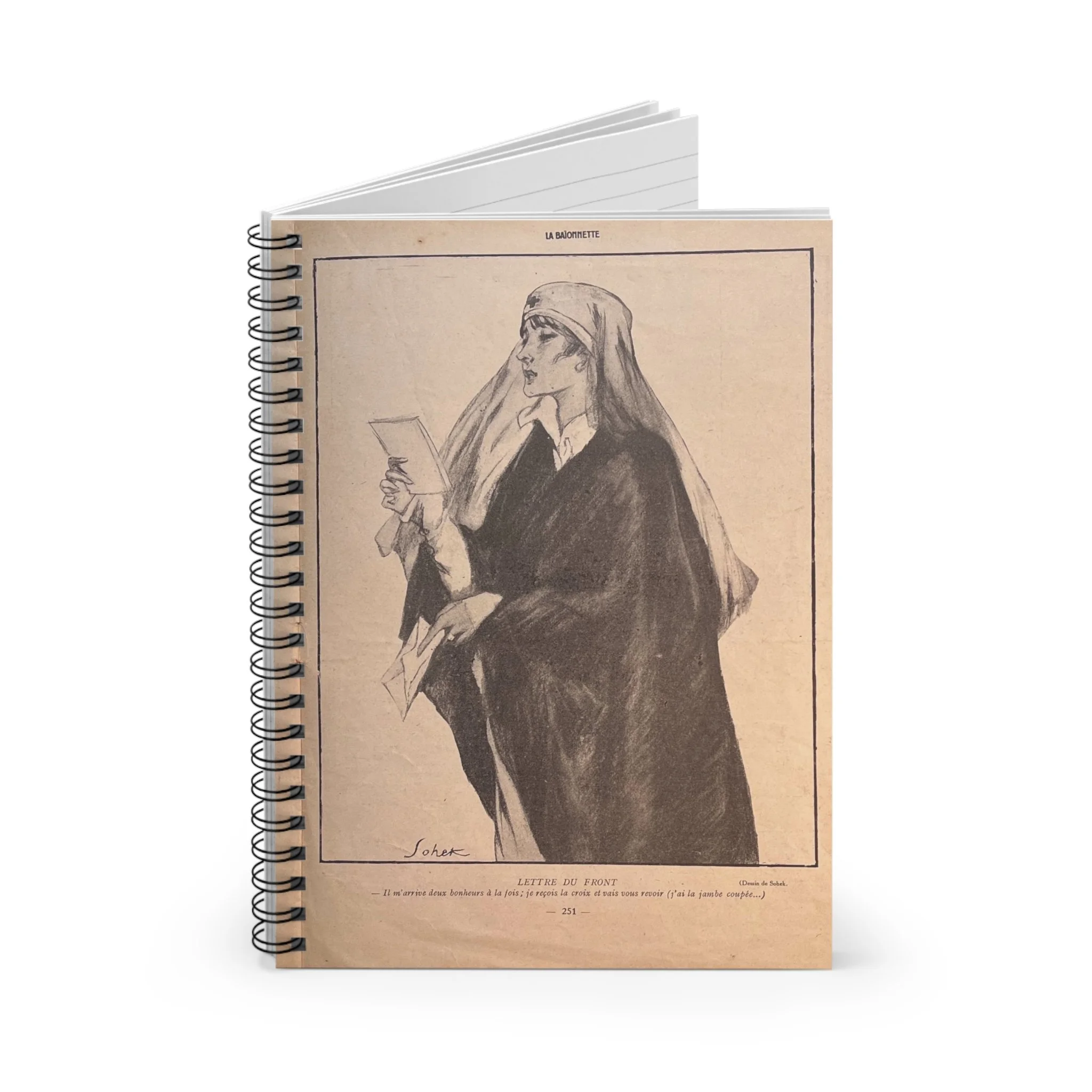

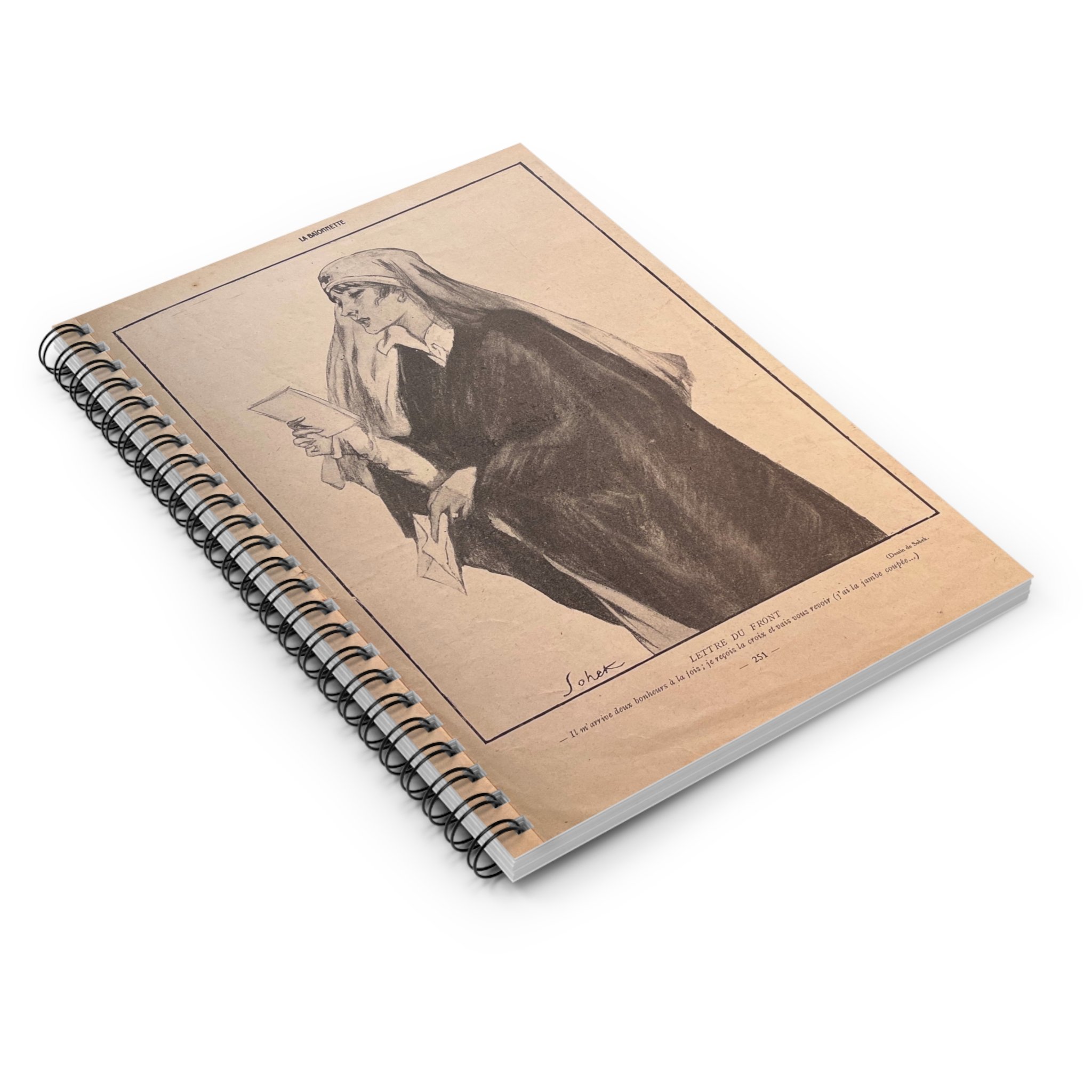

A study in restraint, endurance, and the quiet weight of wartime communication.

The image presents war through pause rather than action, where meaning arrives not in spectacle but in the act of reading. Composure holds, yet strain is evident, suggesting that the deepest costs of conflict are carried inward and revealed through understatement rather than display.

Historical Note

This interior illustration appeared in a 1915 wartime issue of La Baïonnette and was drawn by Sobek. Using minimal gesture and subdued tone, it contrasts official recognition with personal injury to register the human cost of war through stillness.

6 × 8 in | Metal spiral binding | Interior document pocket | Front illustration with dark grey back cover

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

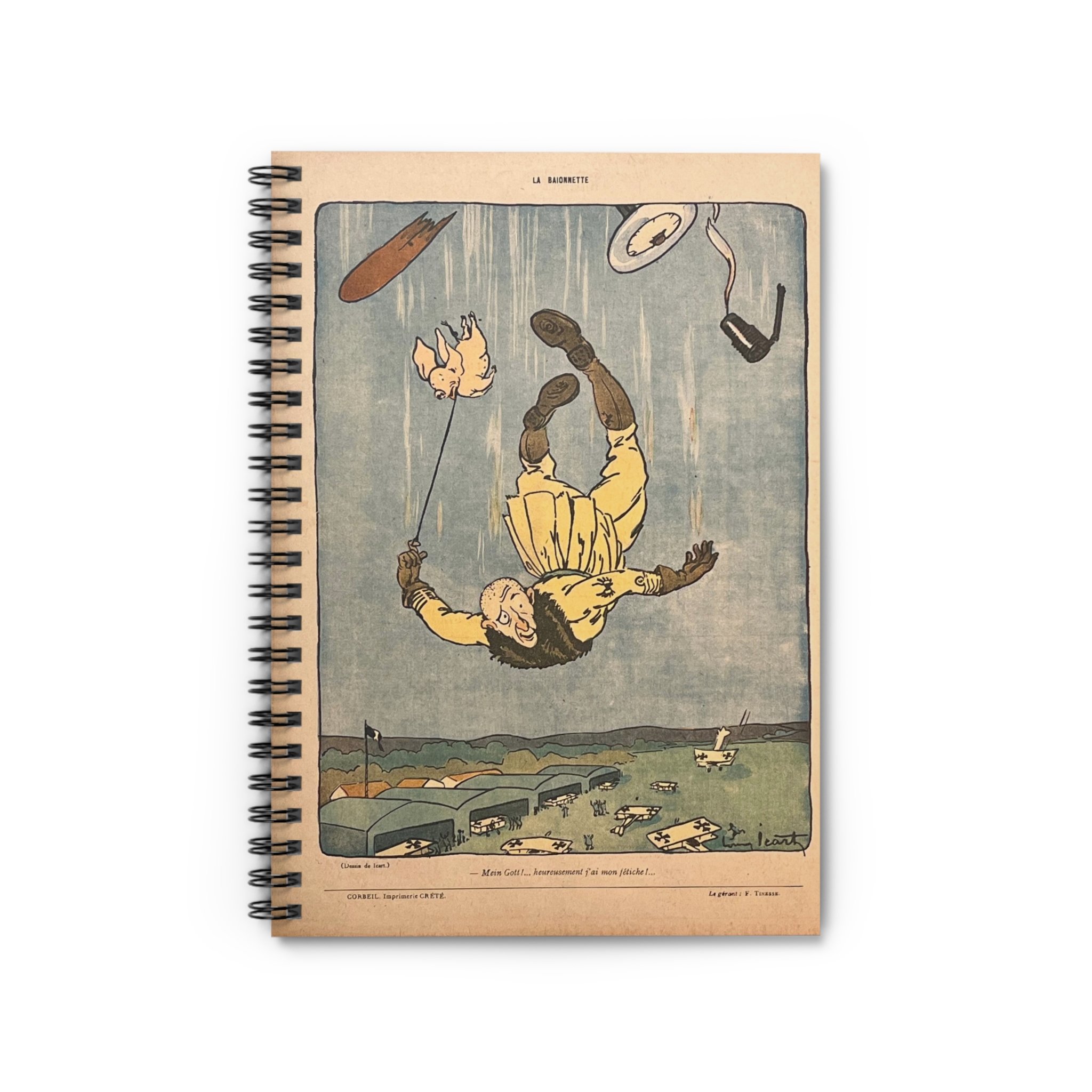

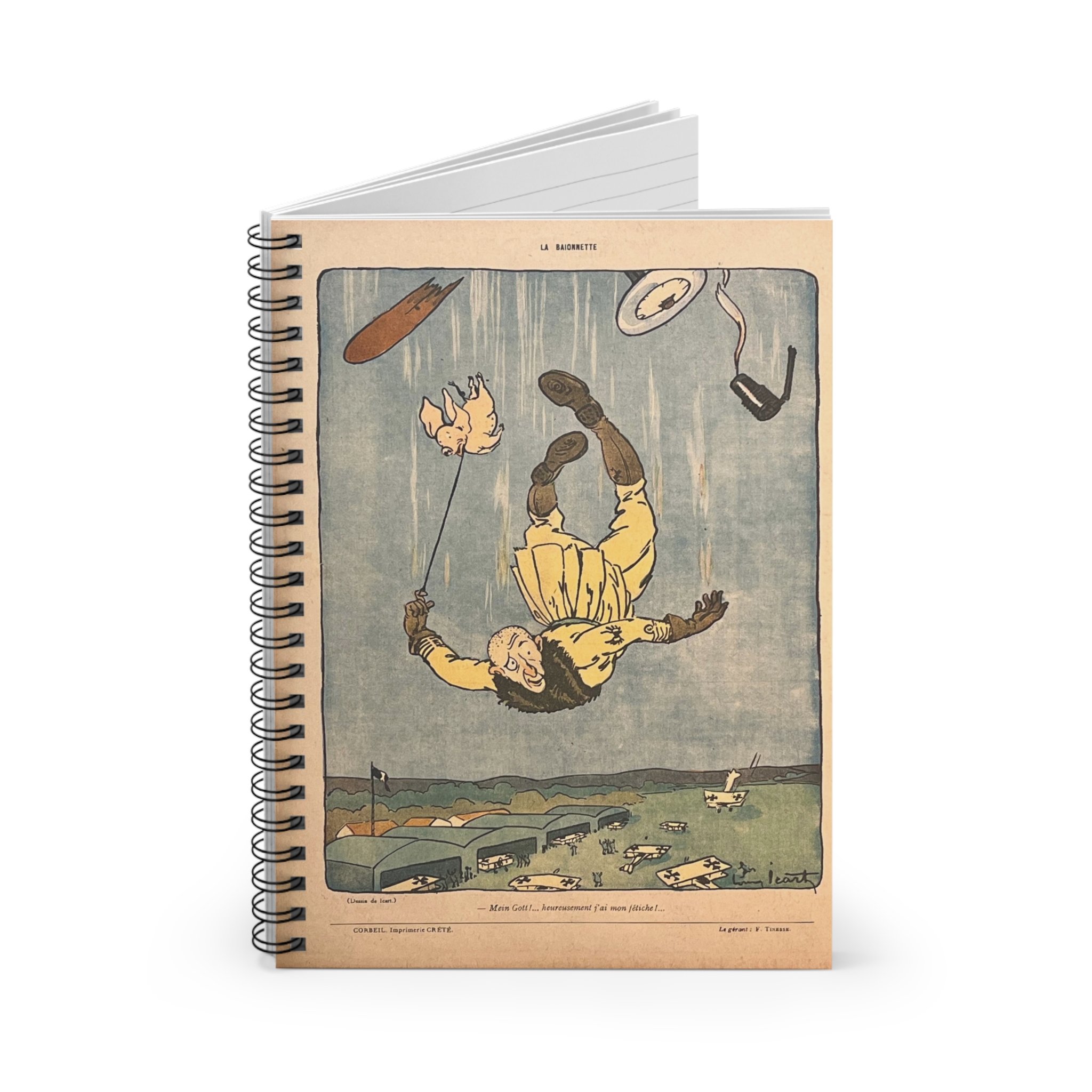

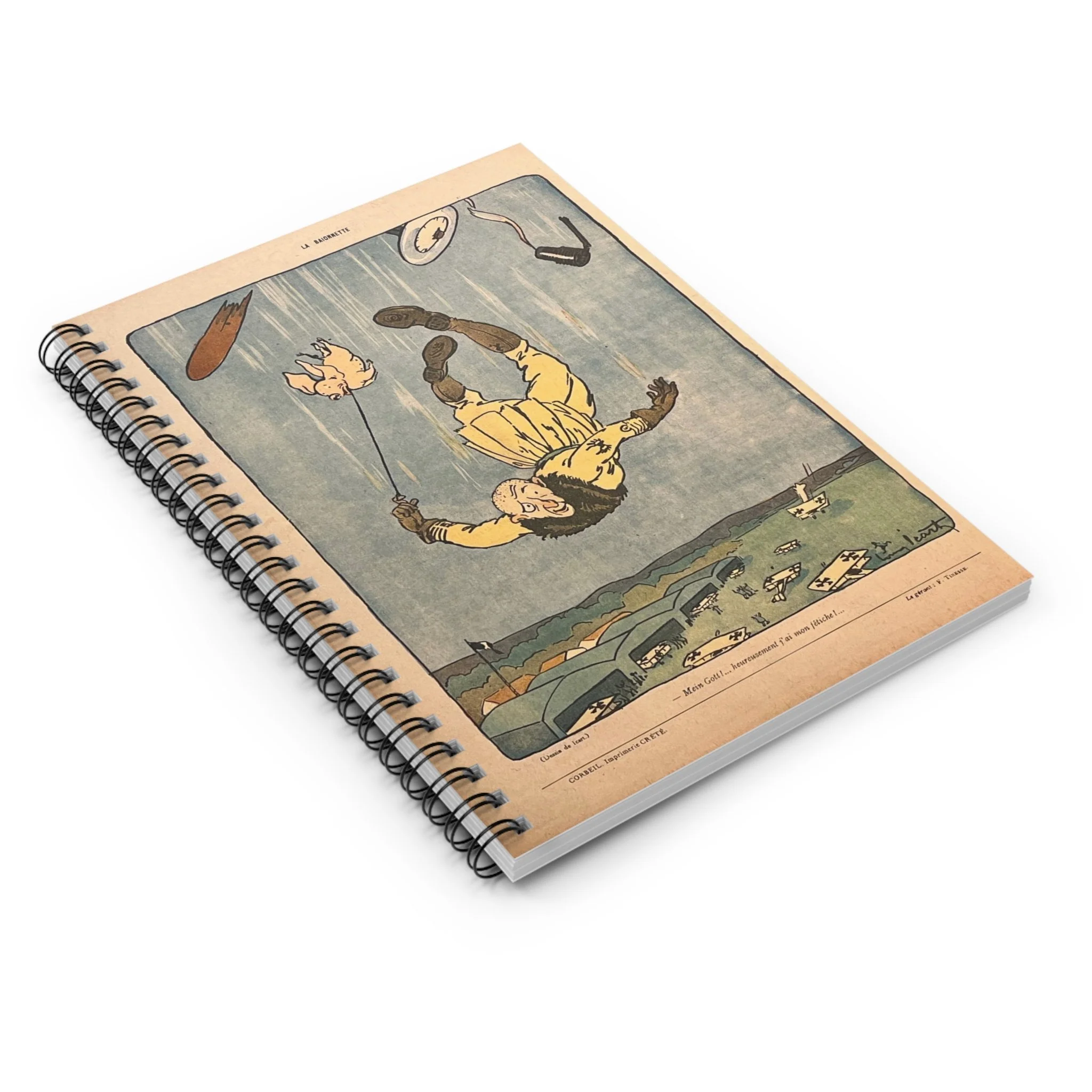

A satirical treatment of superstition, bravado, and the collapse of symbolic authority under violence.

The image depicts confidence unraveling mid-air, where ritual objects and signs of rank offer no resistance once force is unleashed. Assurance gives way to exposure, suggesting that faith in talismans and status dissolves when confronted with material reality.

Historical Note

This cartoon appeared in a 1915 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Louis Icart. It reflects the magazine’s wartime skepticism toward heroic symbolism, using stark humor to show how belief in charms and authority fails under the conditions of modern war.

6 × 8 in | Metal spiral binding | Ruled | Interior document pocket

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

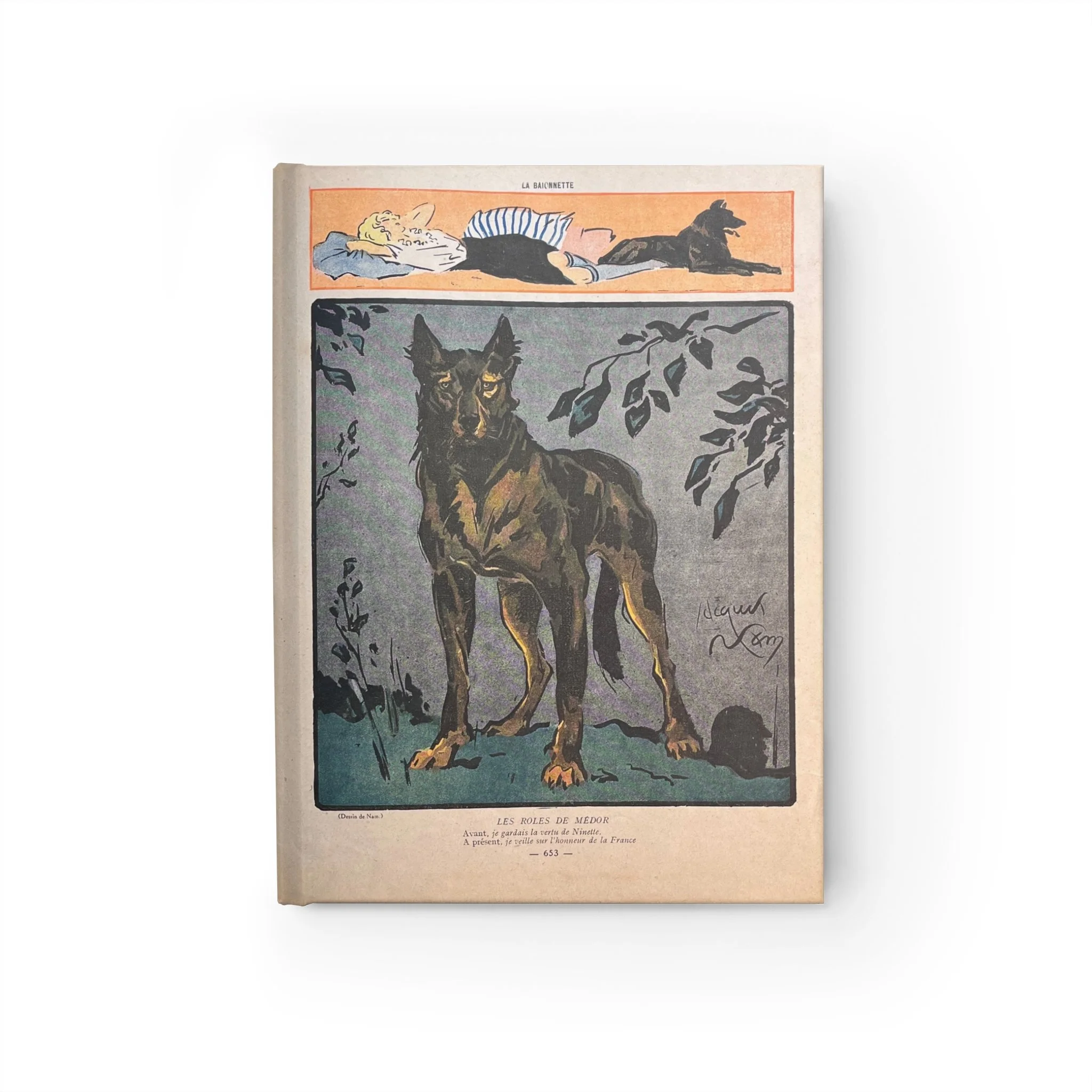

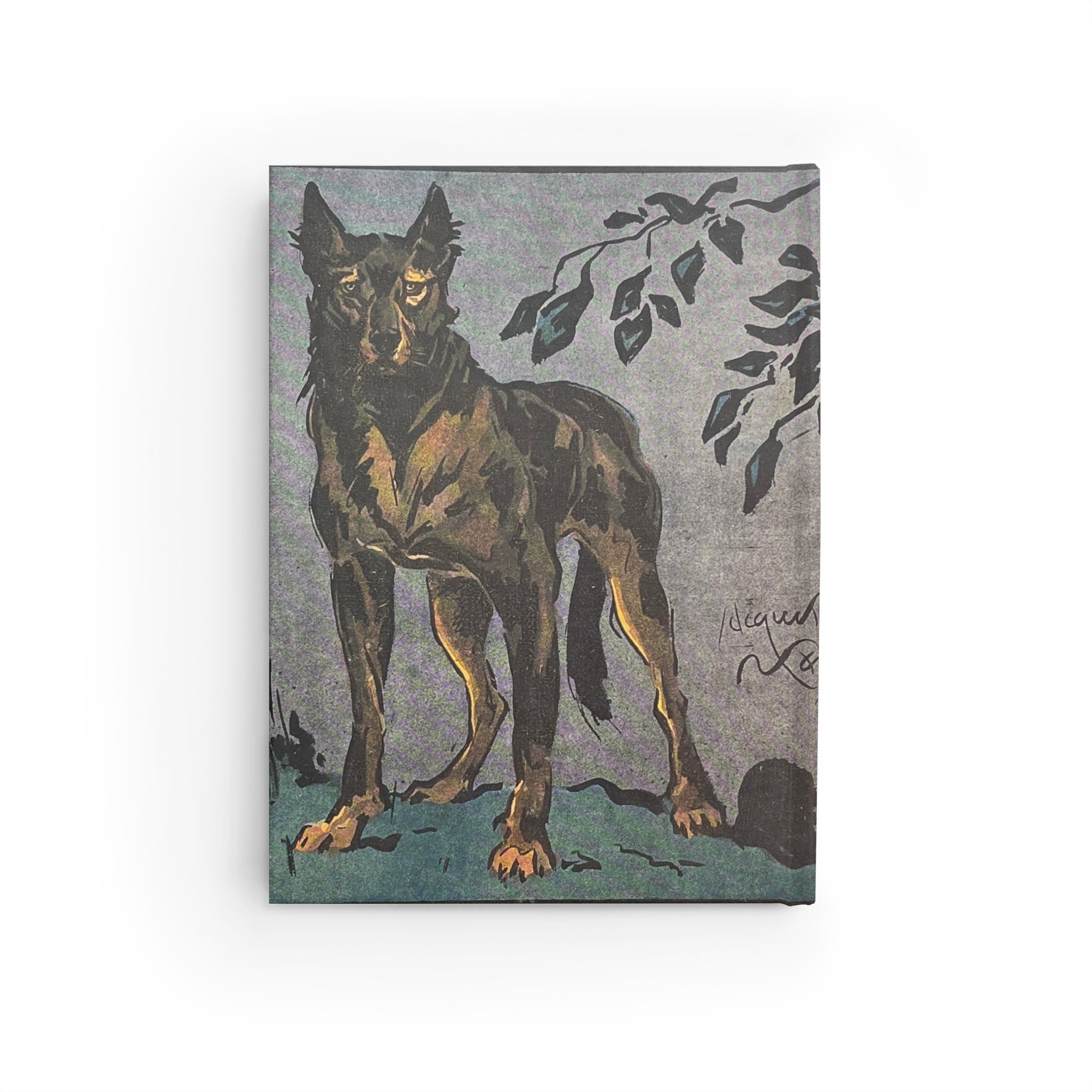

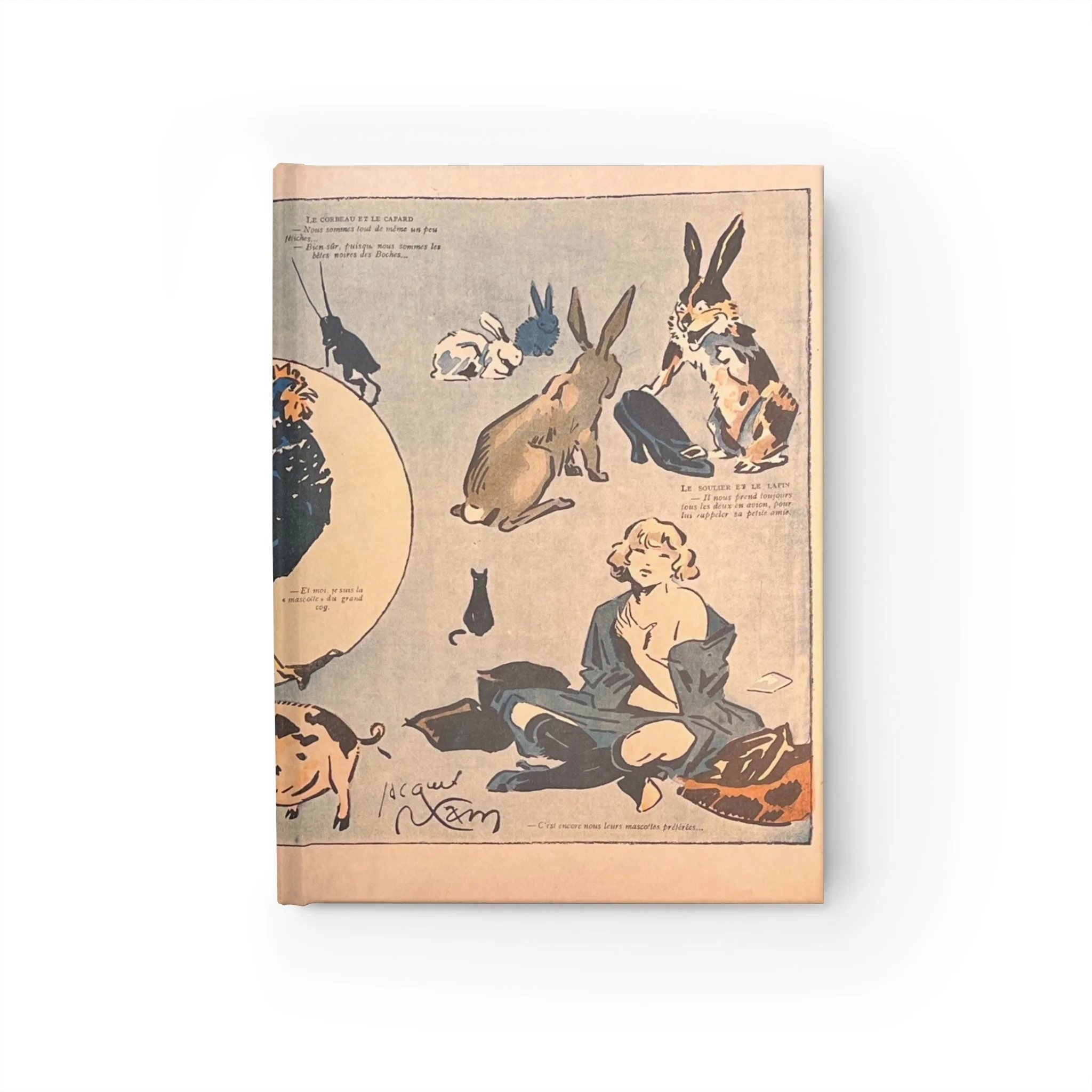

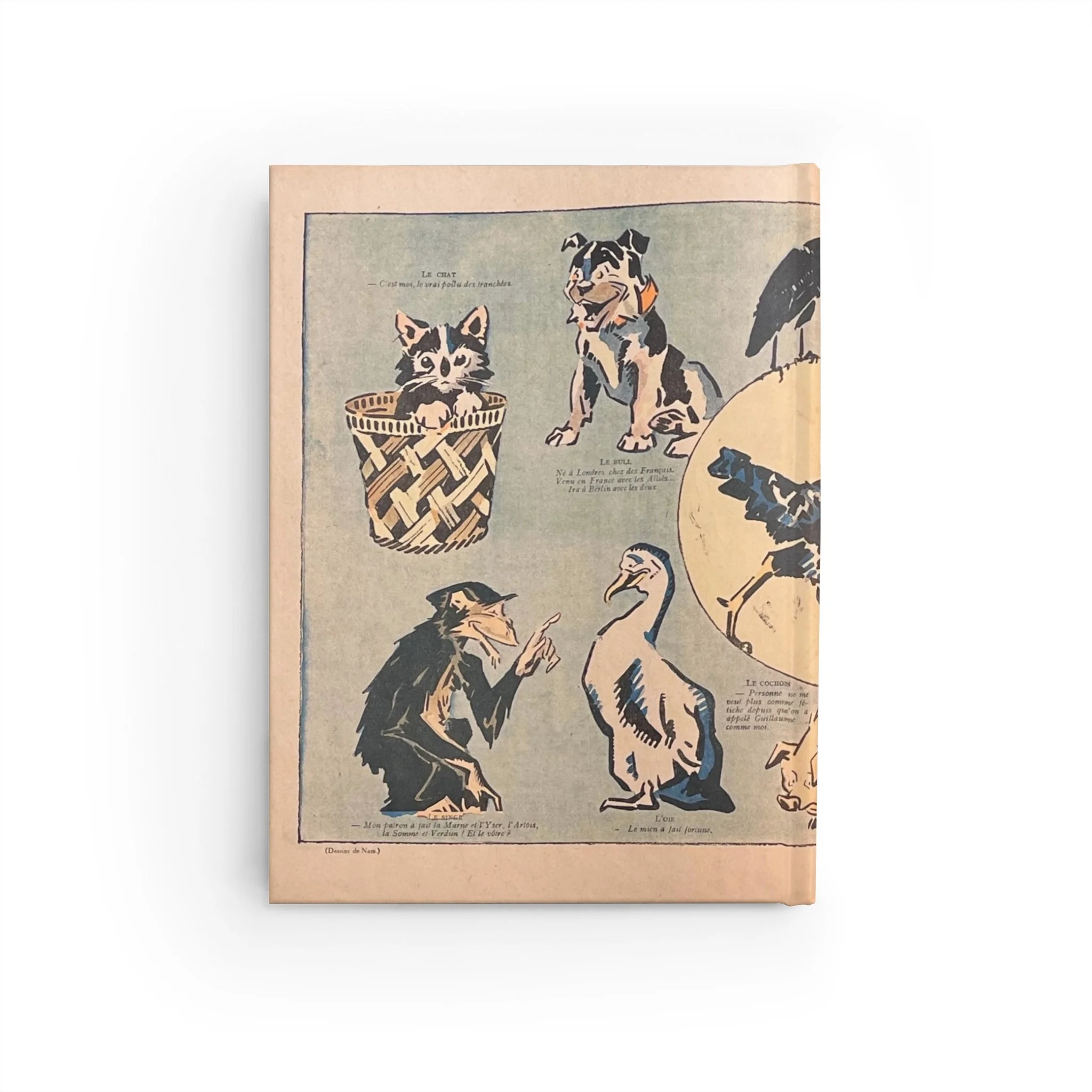

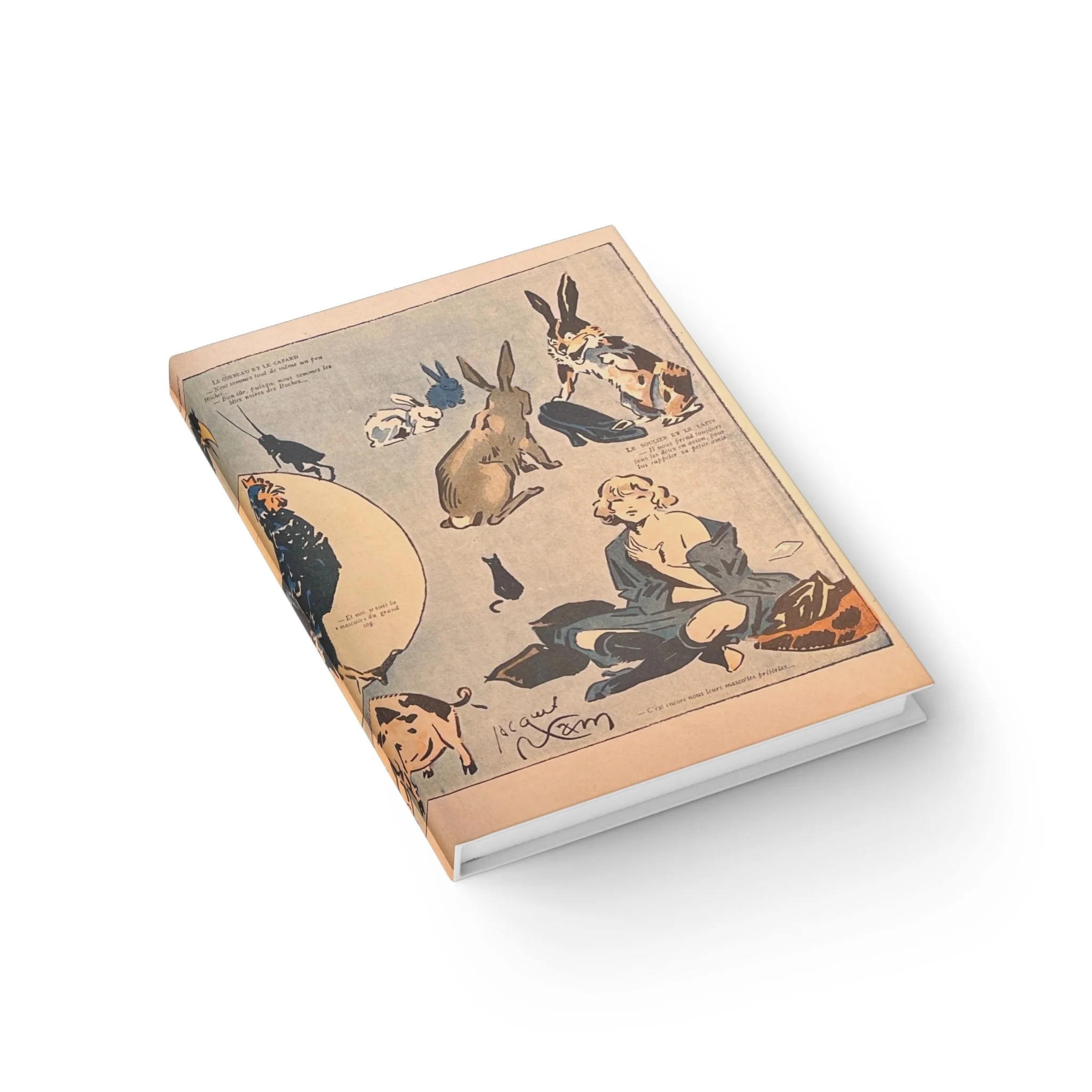

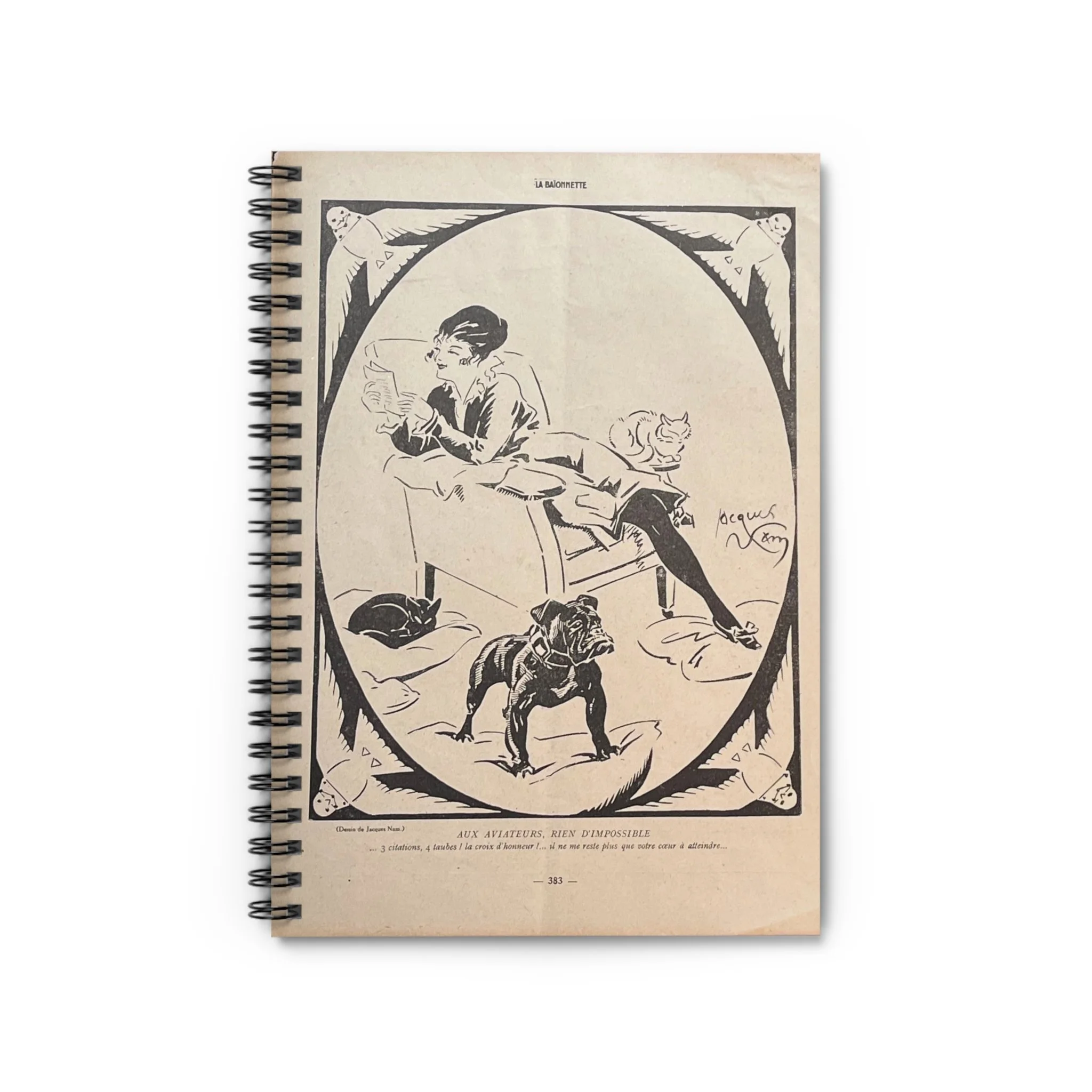

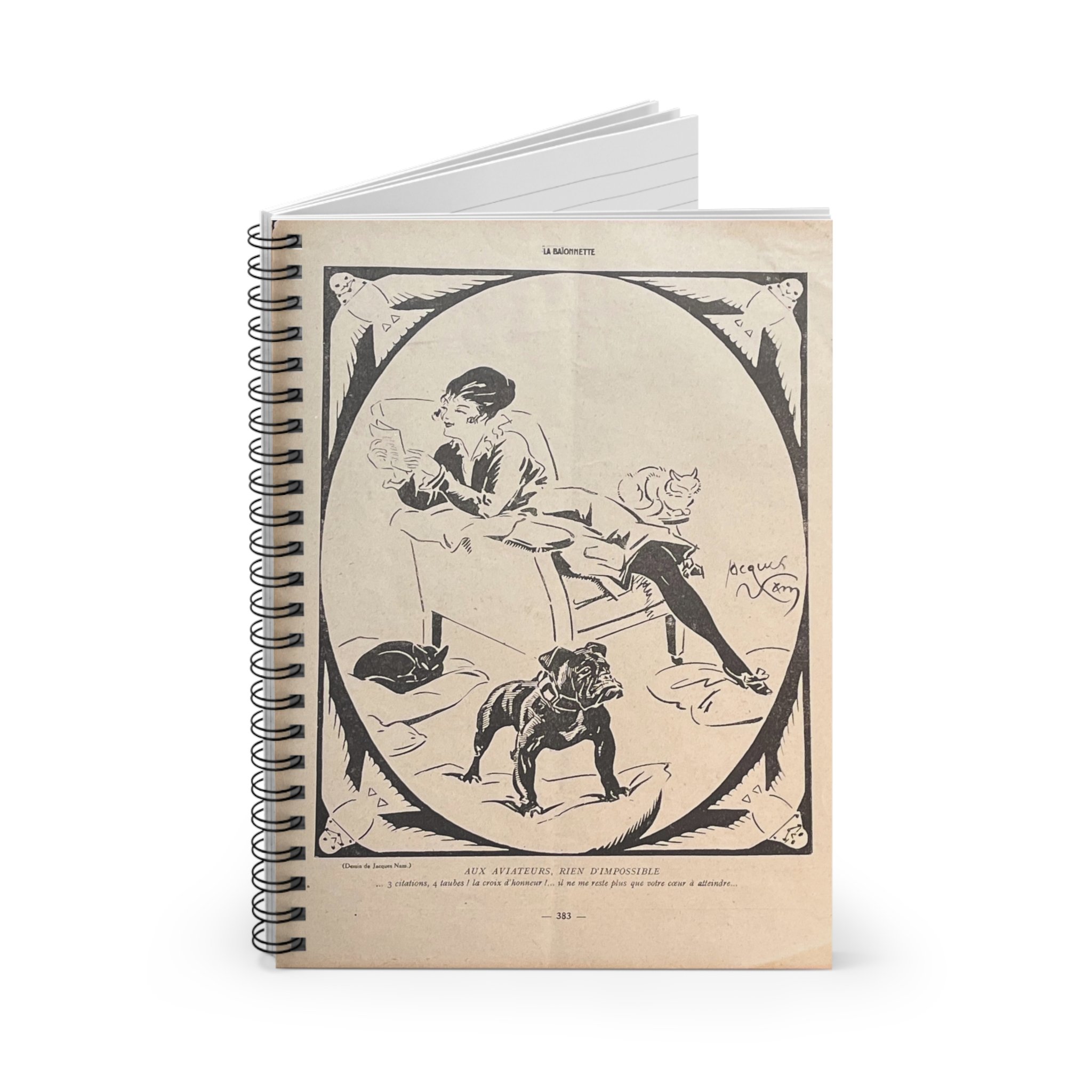

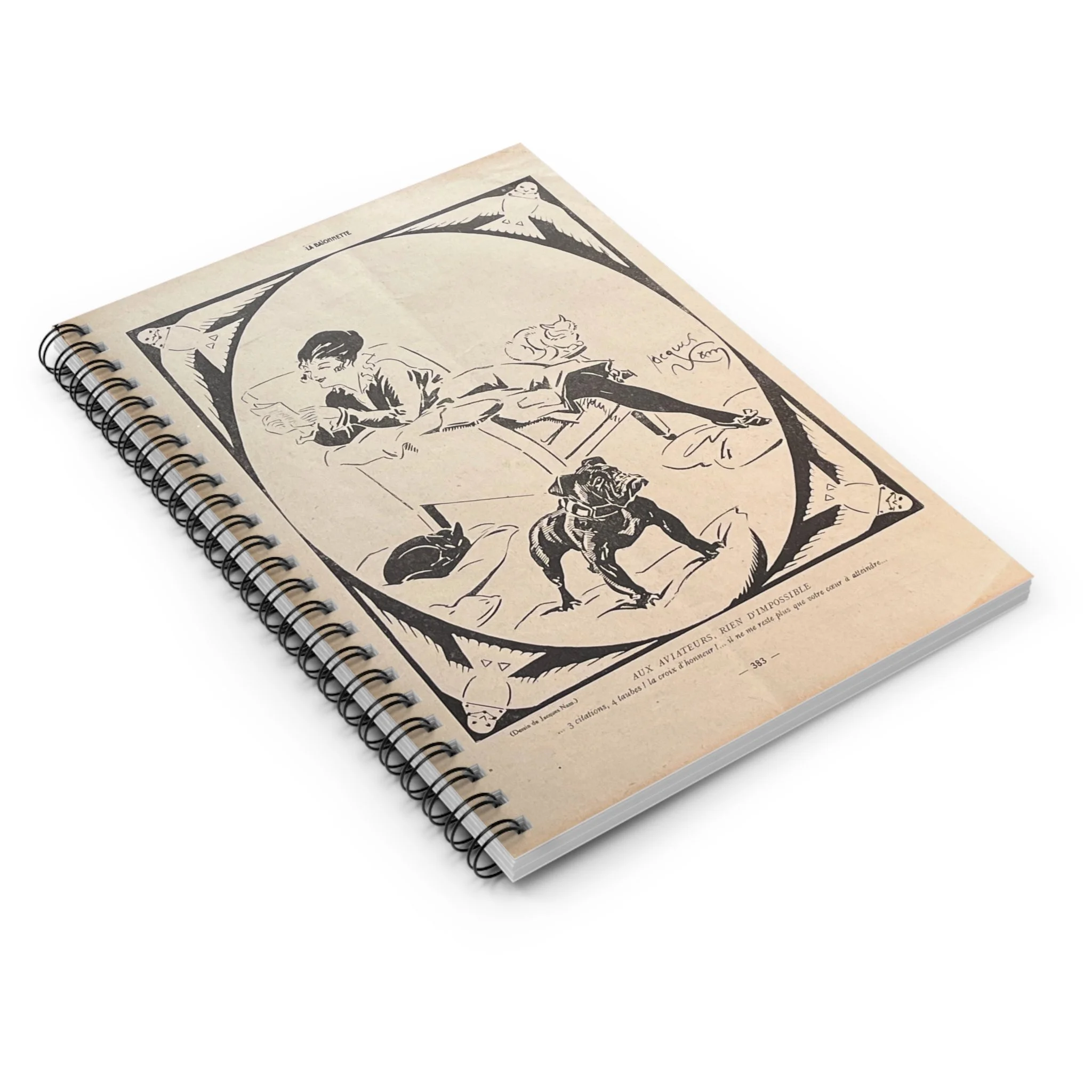

Satire aimed at the redefinition of loyalty under conditions of total war.

The image presents transformation as quiet and unquestioned, where familiar roles are repurposed for national ends. What once belonged to private life is recast as public obligation, suggesting how war absorbs everyday symbols and redirects them toward collective duty.

Historical Note

This page appeared in a 1916 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Jacques Nam. Using a simple two-panel allegory, it reflects how wartime ideology reframed personal loyalty as a resource of the nation.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

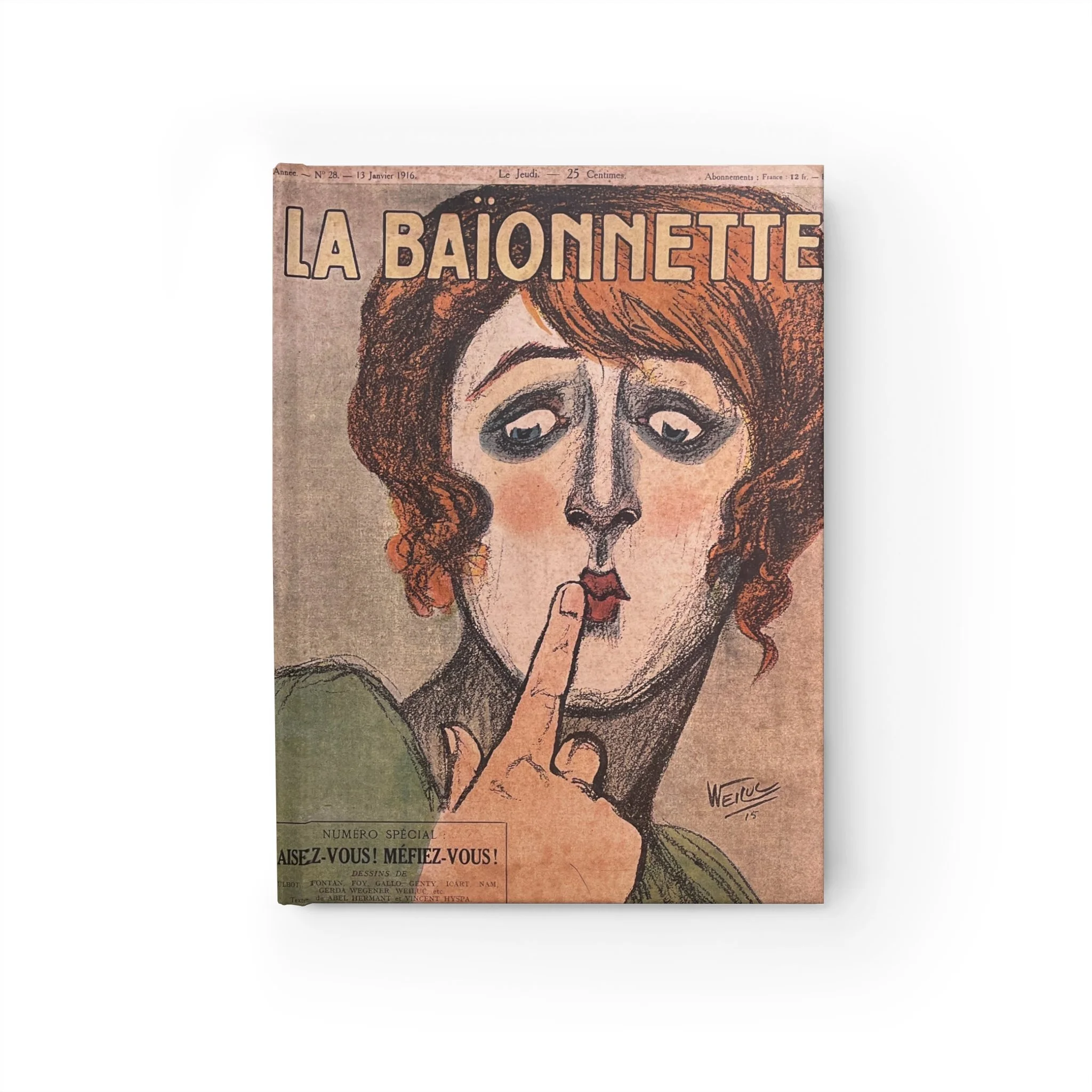

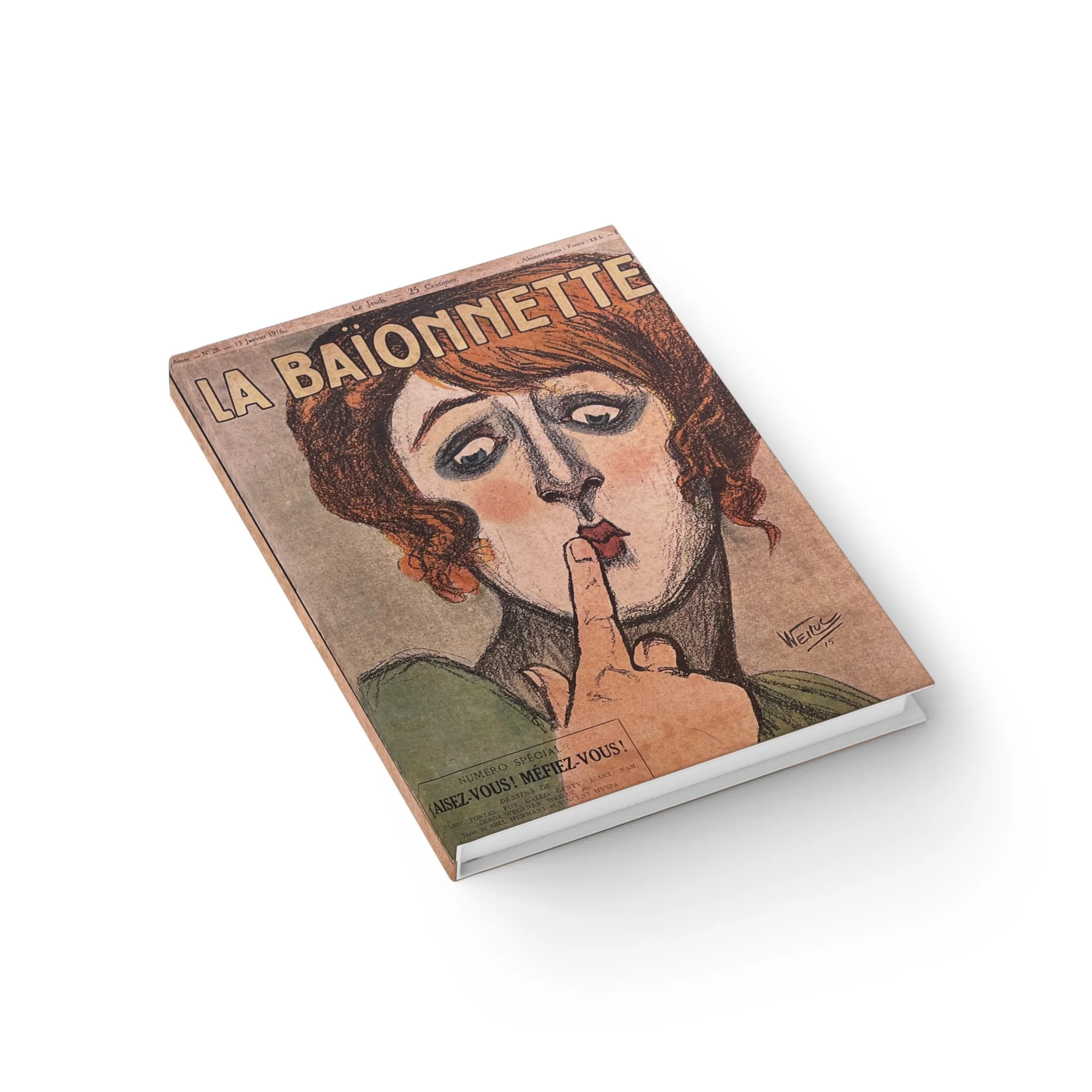

A study of enforced silence and the internalization of surveillance.

The image transforms instruction into performance, where caution is exaggerated and restraint becomes visibly anxious. Speech is shaped less by conviction than by fear, suggesting how censorship migrates from decree into everyday expression.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in a 1916 issue of La Baïonnette and was designed by Lucien-Henri Weiluc. It satirizes home-front censorship during the First World War, using direct address and distortion to register the psychological effects of enforced silence.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

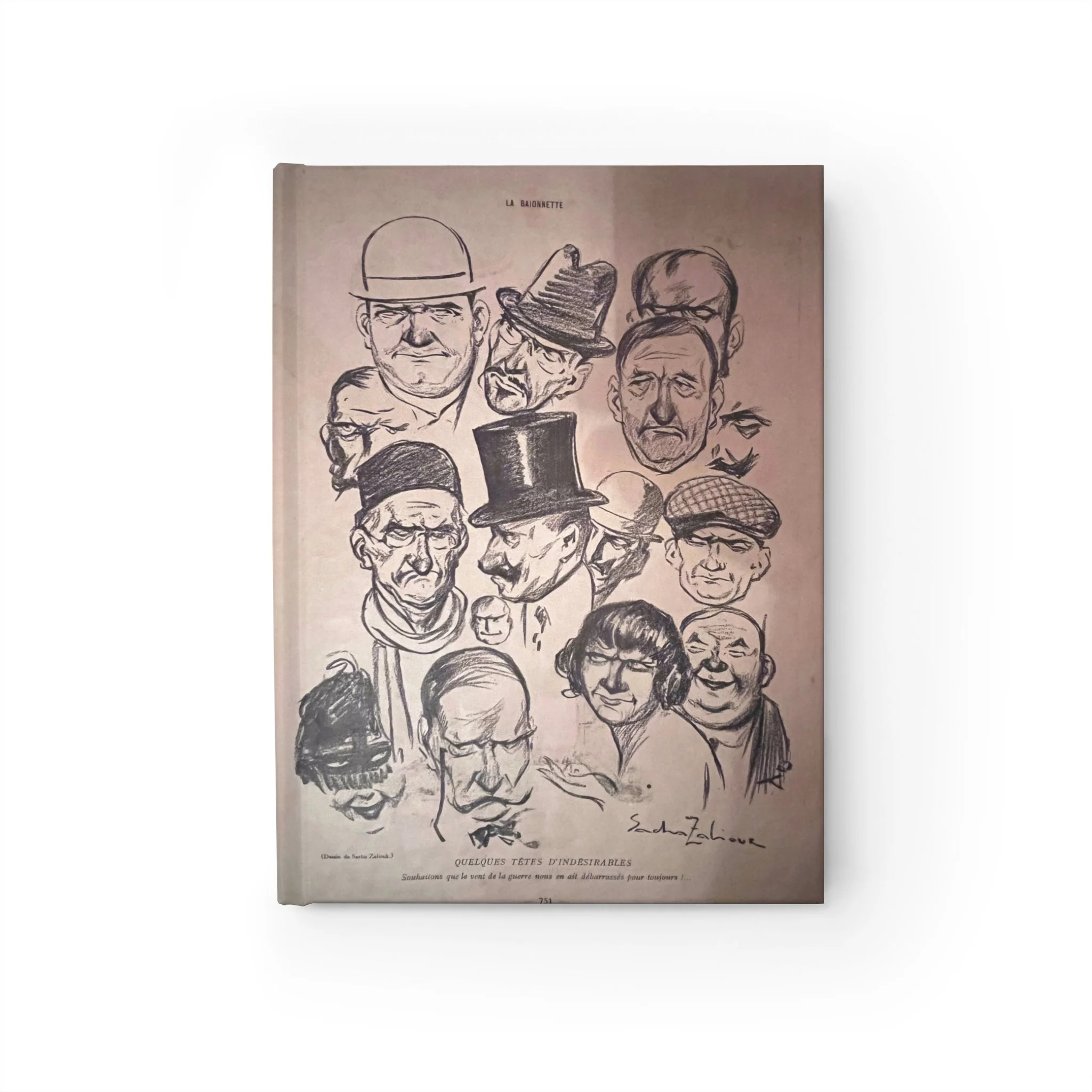

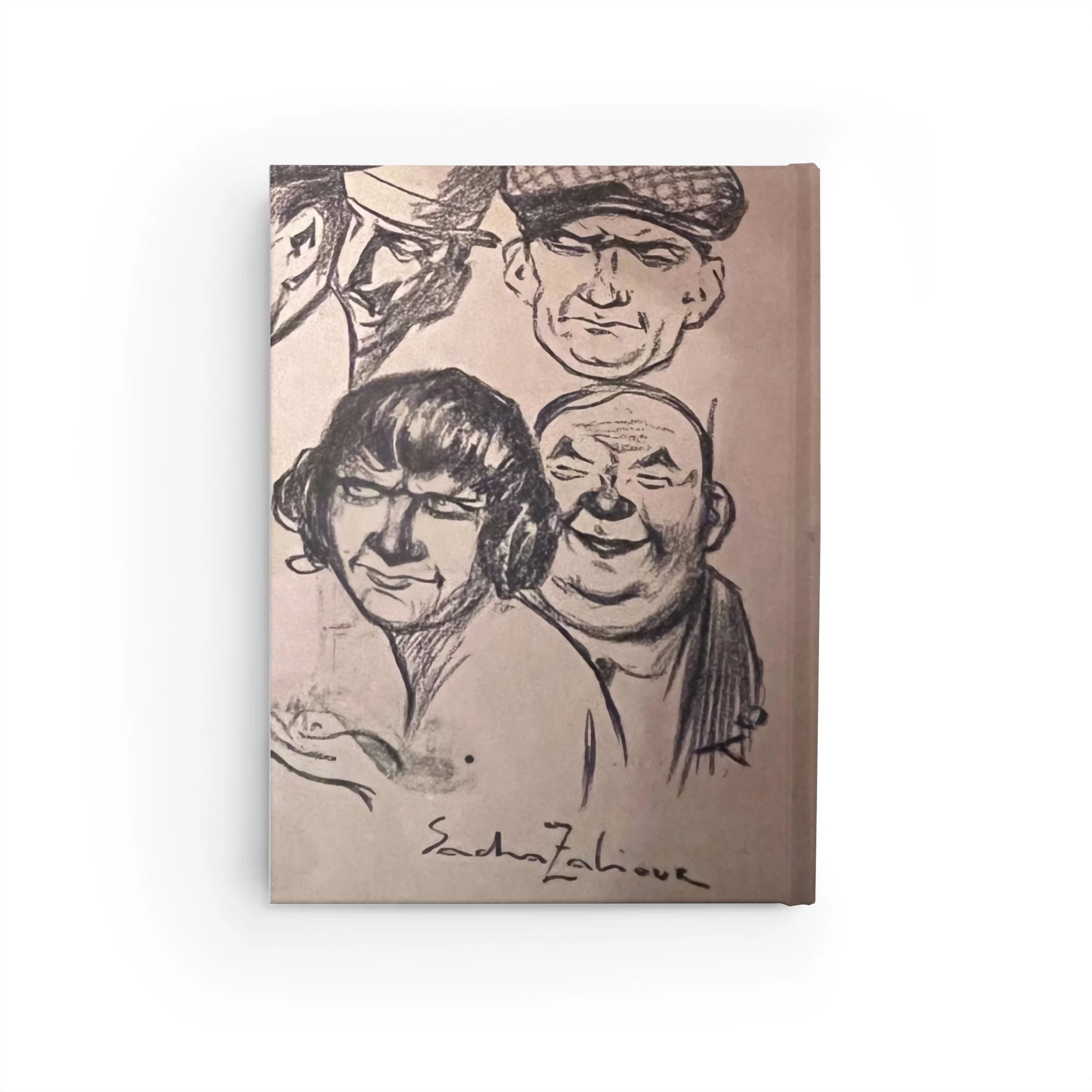

A satirical caricature of accumulation and the persistence of profiteering.

The image isolates figures rather than scenes, reducing corruption to a recognizable inventory of faces. No single actor carries the charge; judgment emerges through repetition, suggesting that exploitation functions collectively and survives by familiarity as much as concealment.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in a 1916 issue of La Baïonnette and was drawn by Sacha Zaliouk. It assembles a typology of wartime profiteers and political operators, using stark caricature to render corruption as a social pattern rather than an exception.

5.75 × 8 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

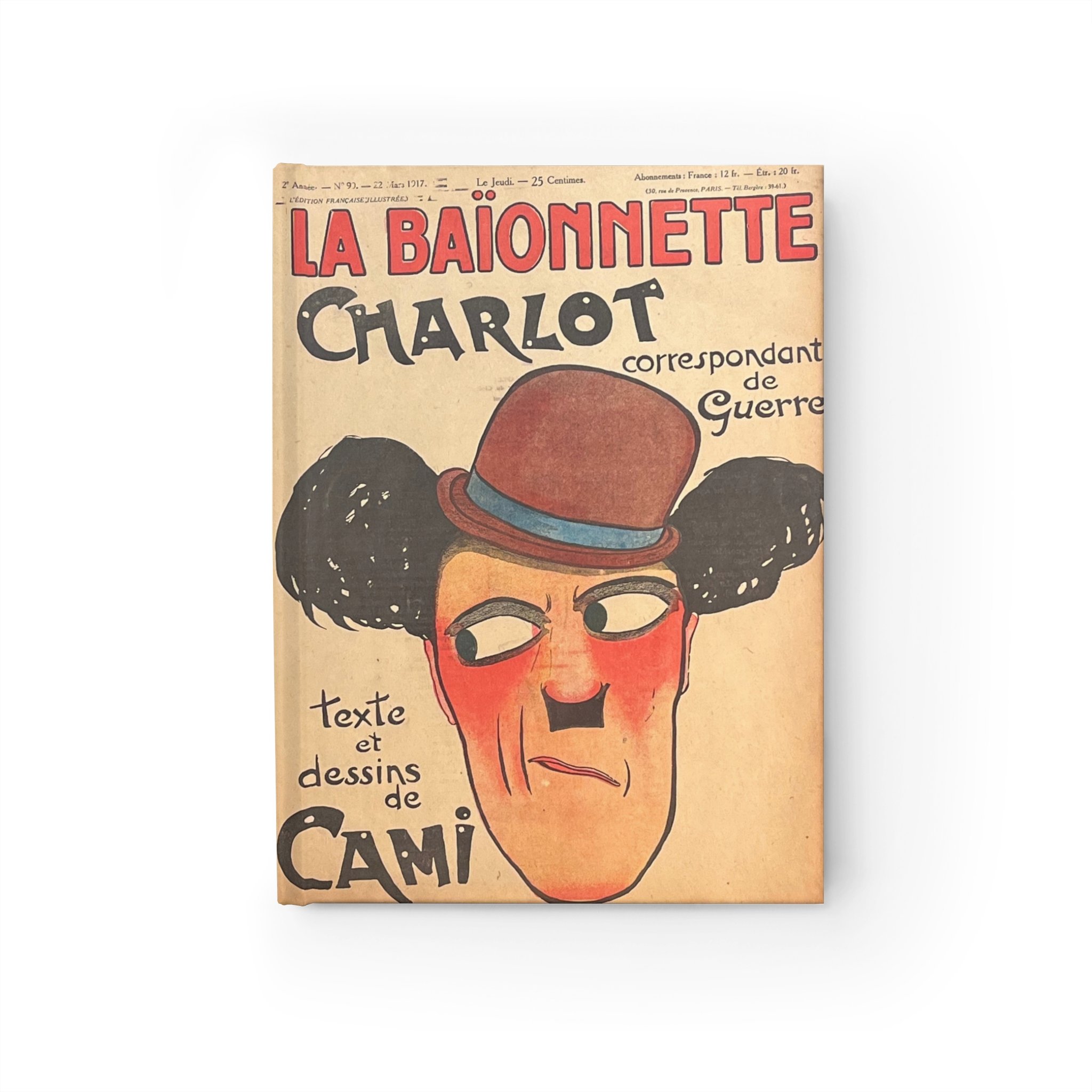

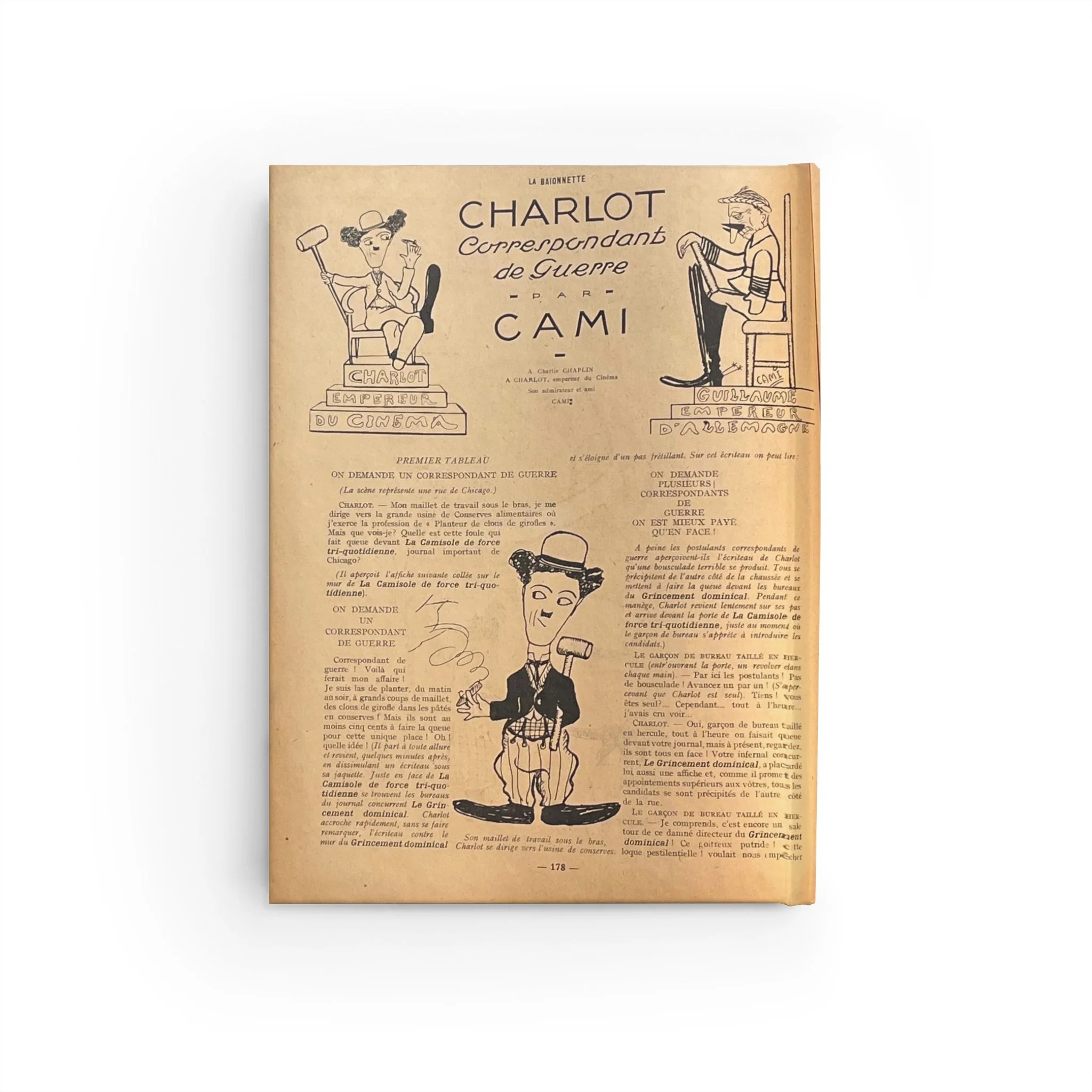

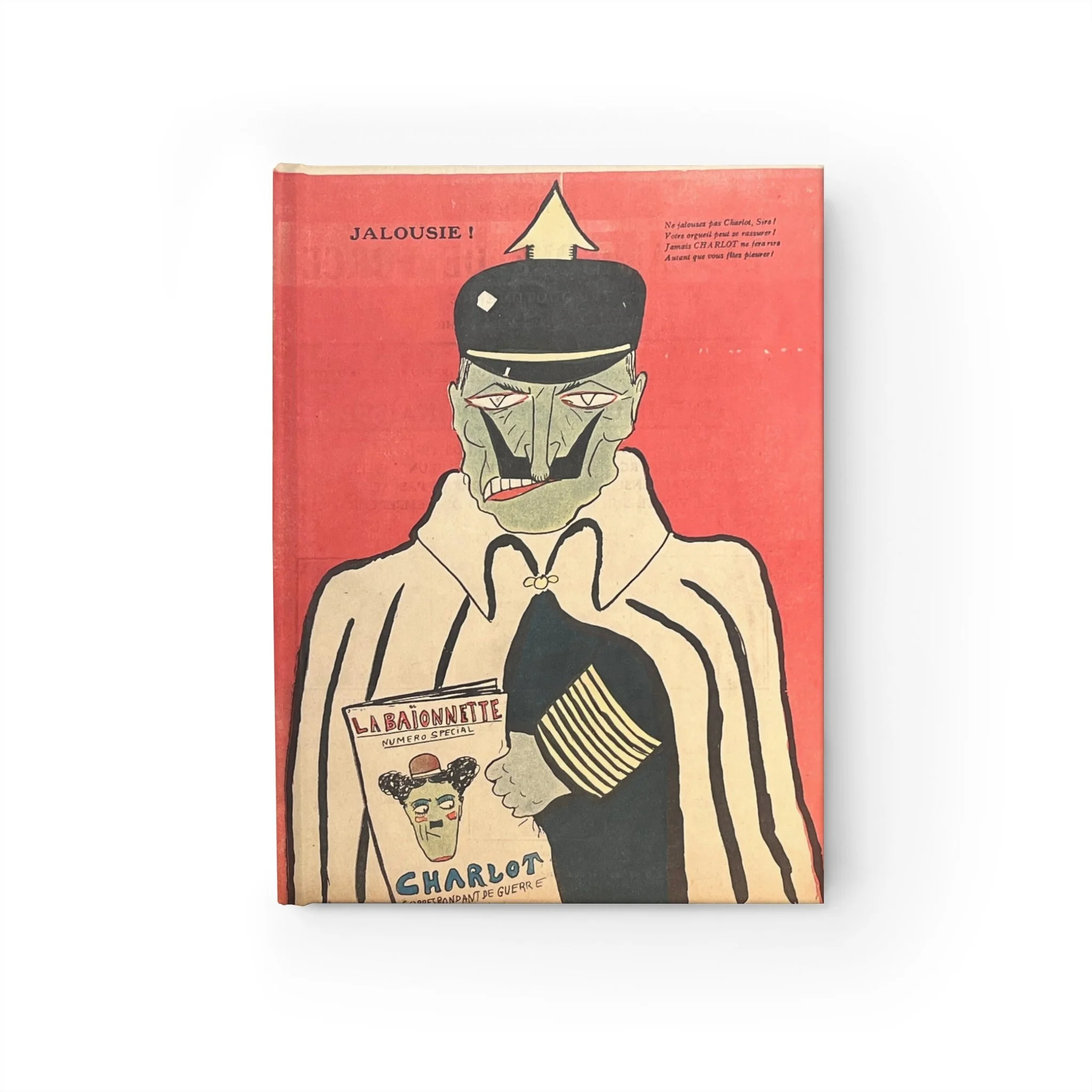

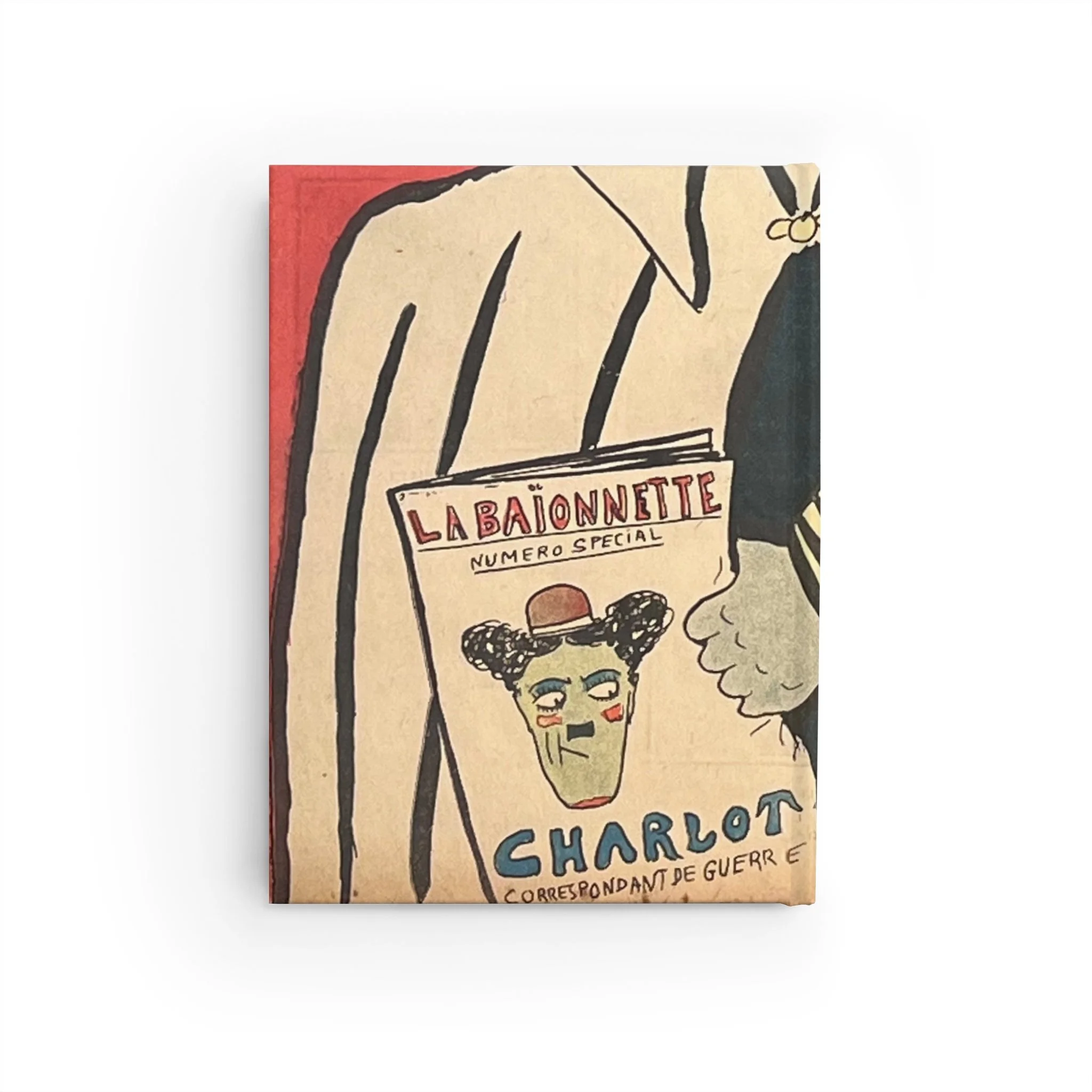

Satire aimed at theatrical authority and the absurd logistics of war.

The image treats conflict not as heroism or tragedy, but as a stage crowded with gesture, repetition, and bureaucratic confusion. Power appears costumed and performative, exposing how military life converts spectacle into routine and survival into farce.

Historical Note

This 1917 cover from La Baïonnette introduces Pierre-Henri Cami’s satirical feature “Charlot correspondant de guerre,” a wartime parody of Charlie Chaplin’s screen persona. The subtitle “texte et dessins de Cami” signals the issue’s focus on Charlot as a caricatured war correspondent navigating military absurdity. The back cover reproduces material from the same March 22, 1917 issue, preserving Cami’s line drawings and original French dialogue as they appeared in print.

See the full Cami: Charlie Chaplin Collection here

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A satirical critique of authoritarian vanity and wounded imperial pride.

The image presents power as reactive and insecure, where command is unsettled by ridicule and popularity beyond its control. Exaggerated expression and posture turn authority inward, exposing how spectacle and resentment replace confidence when legitimacy falters.

Historical Note

This illustration appeared in a 1917 issue of La Baïonnette and was created by Pierre-Henri Cami. Titled Jalousie!, it depicts Kaiser Wilhelm II reacting to the popularity of Charlot, using caricature to mock imperial vanity and fragility during the First World War.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

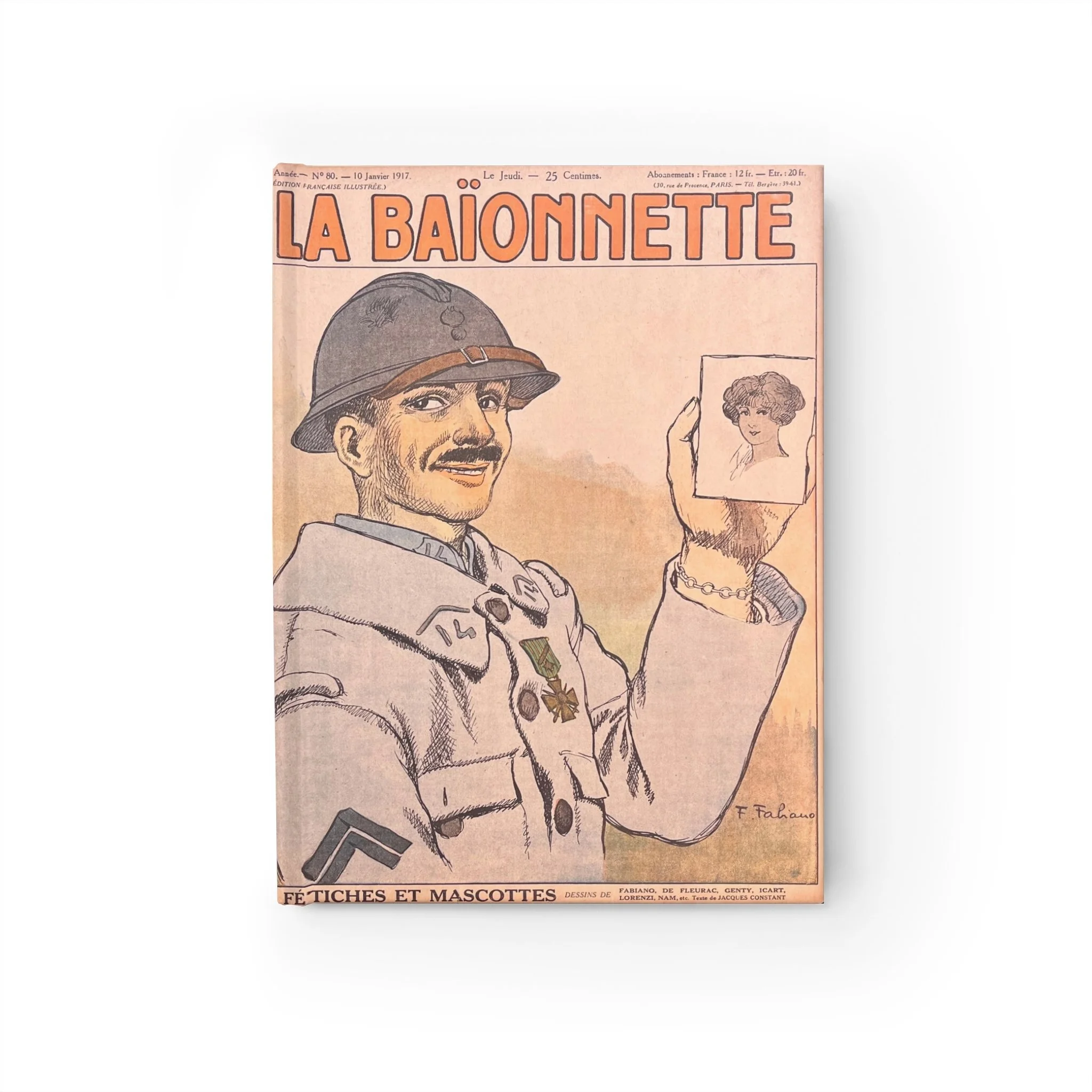

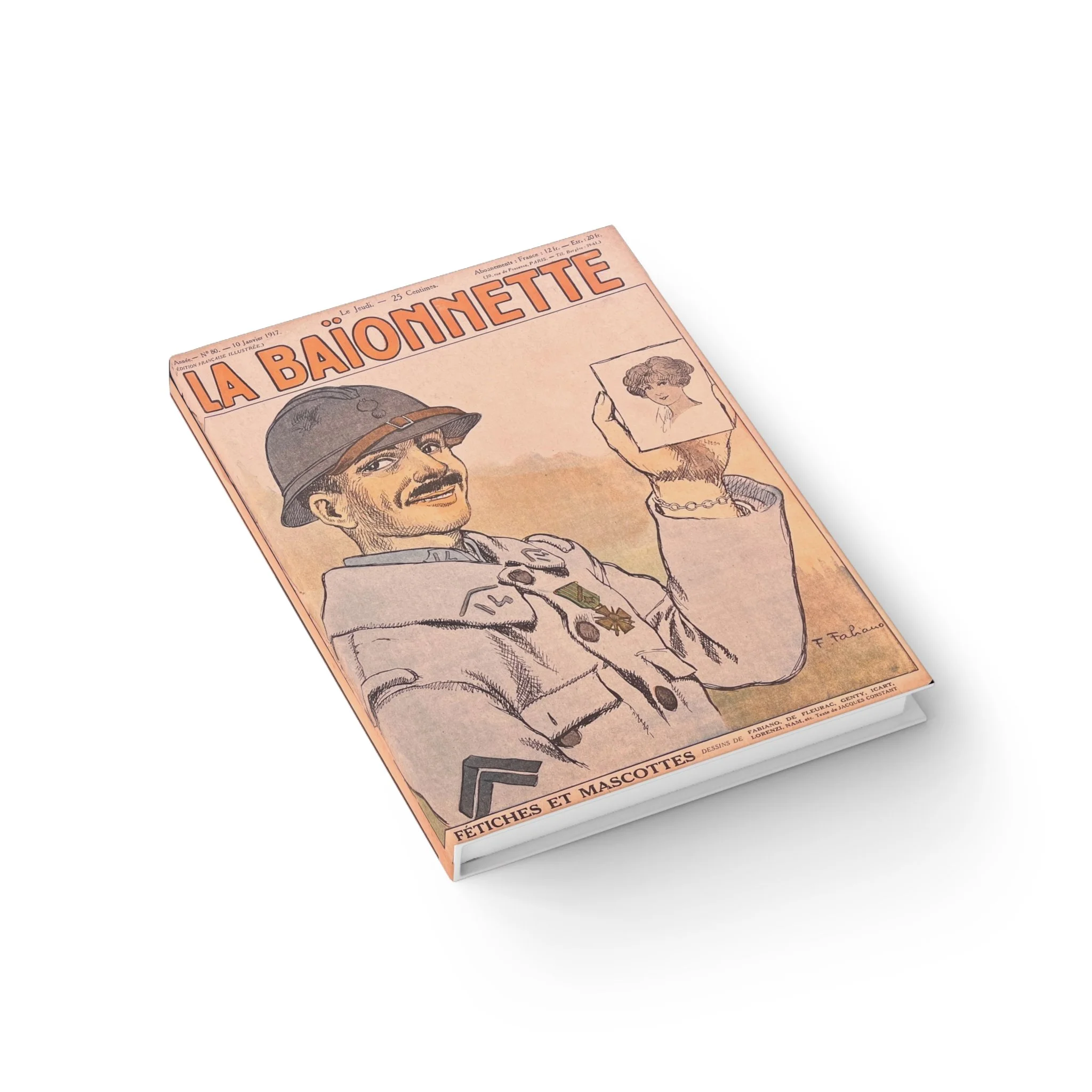

An examination of emotional substitution and the management of fear through symbol.

The image presents intimacy as something compressed and portable, where affection is converted into an object meant to steady the bearer. Comfort appears ritualized rather than relational, suggesting how war reshapes private attachment into a tool for endurance amid industrial violence.

Historical Note

This cover appeared in a January 1917 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Fabien Fabiano. Titled Fétiches et Mascottes, it reflects wartime practices that encouraged soldiers to rely on talismans and symbolic objects as emotional stabilizers.

Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A study in symbolic belief and the everyday rituals of wartime life.

The image assembles a loose catalogue of objects and figures treated as carriers of meaning, luck, or morale. Without privileging command or combat, it presents superstition as ordinary and pervasive, where official emblems and private rituals coexist without clear hierarchy.

Historical Note

This centerpiece appeared in a January 10, 1917 issue of La Baïonnette and was illustrated by Jacques Nam. It surveys the fetishes, mascots, and symbolic stand-ins that circulated through the French army during the First World War, registering belief as a shared cultural practice rather than an anomaly.

5 × 7 in | Casewrap sewn binding | Ruled | Vibrant, crisp vintage tones

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

A depiction of inflated rhetoric and the quiet persistence of ordinary life.

The image sets domestic stillness against proclamations of boundless achievement, letting contrast do the work of critique. Heroic language is framed as overreach, while intimacy and calm remain intact—suggesting that progress and glory often sound loudest where their effects are least felt.

Historical Note

This illustration by Jacques Nam appeared during the First World War in a 1917 issue of La Baïonnette. It exemplifies a strand of wartime satire that uses irony and juxtaposition—rather than spectacle—to puncture claims of inevitability and triumph.

6 × 8 in | Metal spiral binding | Ruled | Interior document pocket

Add two journals to your cart to receive an automatic bundle discount.

No results match your search. Try removing a few filters.