Victor Gillam | 1858-1920

Life & Work

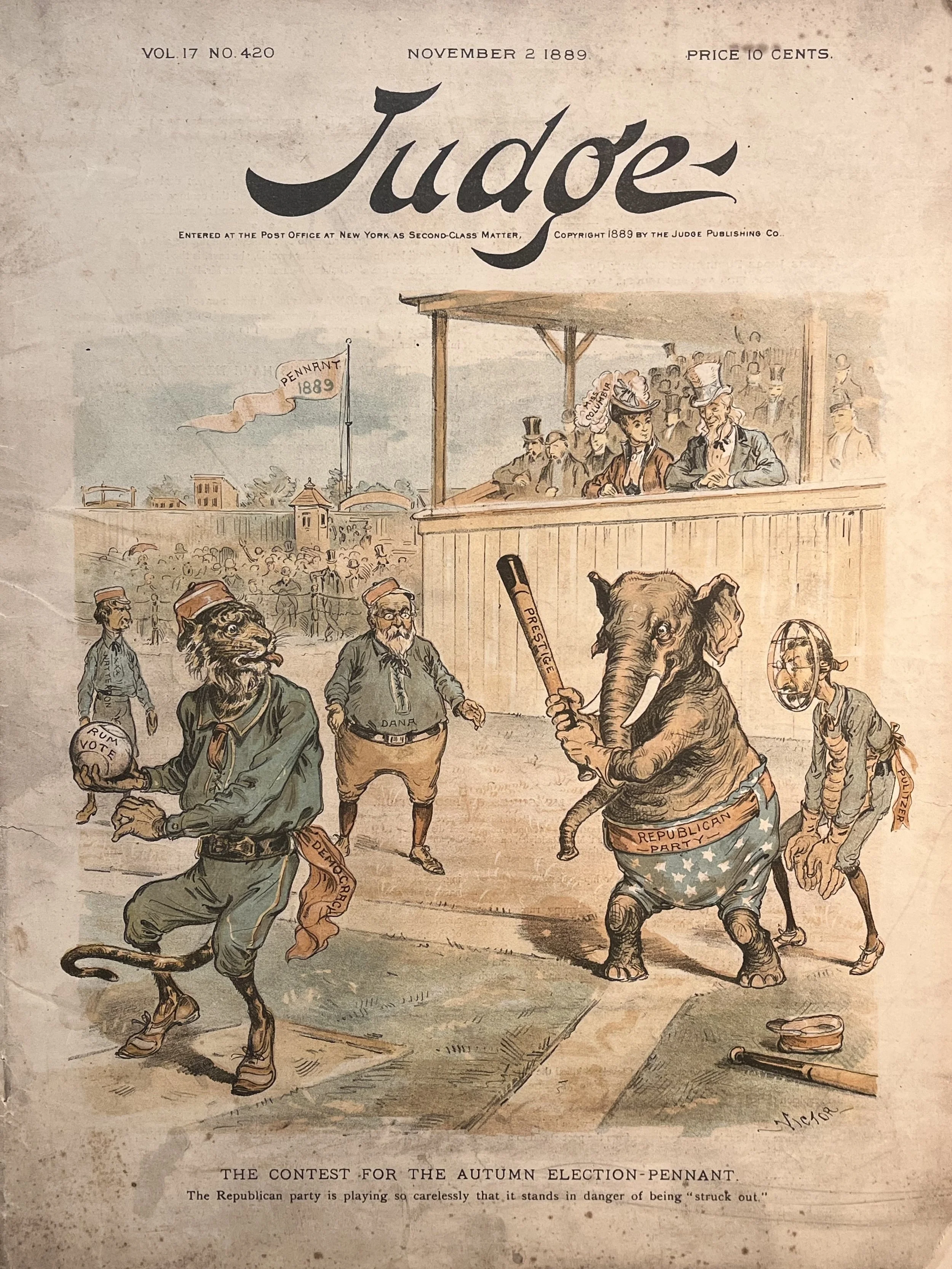

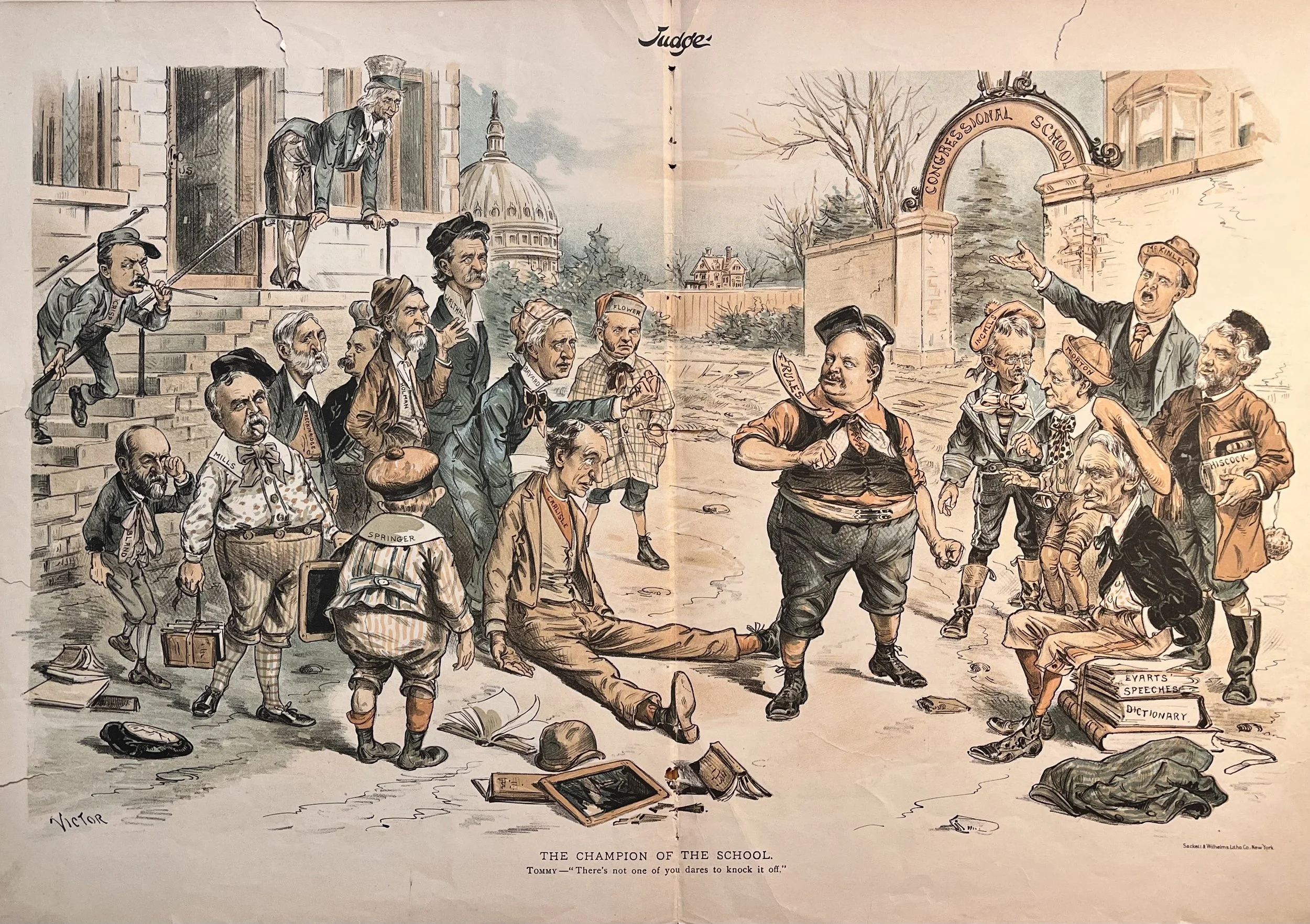

Victor Gillam (1858–1920) was an American political cartoonist whose work appeared most prominently in Judgemagazine during the final decades of the nineteenth century. Born in Yorkshire, England, he emigrated to the United States as a child and came of age professionally within the expanding world of illustrated political journalism.

Gillam worked for Judge for roughly twenty years, producing large-format cartoons designed for national circulation. His illustrations also appeared in major newspapers including the St. Louis Dispatch, Denver Times, New York World, and New York Globe, placing his work at the intersection of magazine satire and daily political commentary. He was active in New York’s press culture and affiliated with professional clubs that connected illustrators, editors, and journalists.

The younger brother of Bernhard Gillam (1856-1896), Victor initially signed his work “Victor” or “F. Victor,” distinguishing himself within a shared family reputation for political illustration. His career coincided with the peak influence of illustrated satire as a mass political medium, before photography and headline-driven journalism displaced it.

Political Focus

Gillam’s cartoons operate through structure rather than caricature alone. His images repeatedly stage political life as a system of competing forces—parties, institutions, economic interests—rather than as a contest of personalities. Allegory, labeling, and carefully balanced compositions allow complex arguments to unfold within a single frame.

While Gillam’s work includes material supportive of mainstream party politics, including Republican campaigns of the 1890s, his cartoons consistently reveal an underlying anxiety about spectacle, public persuasion, and the machinery of power. Elections, reform movements, and national ambition are shown as performances requiring constant management and control.

In works addressing world’s fairs, imperial posture, or public health scares, Gillam anticipates consequences rather than celebrates progress. Authority is framed as provisional and vulnerable, its confidence shadowed by instability. Within Judge, his cartoons contributed to a visual culture that encouraged readers to recognize politics as something constructed—and therefore open to scrutiny.