Joseph Keppler | 1838-1894

Life & Work

Joseph Keppler was born in Vienna in 1838 and trained at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, where he absorbed the dense allegorical style of German caricature. Early in his career he worked not only as an artist but as an actor, touring with theatrical companies across Central Europe—a background that would later inform the dramatic staging and crowd-filled compositions of his cartoons. His first published illustrations appeared in the satirical magazine Kikeriki before he emigrated to the United States in 1867, initially settling in St. Louis within a large German-American community.

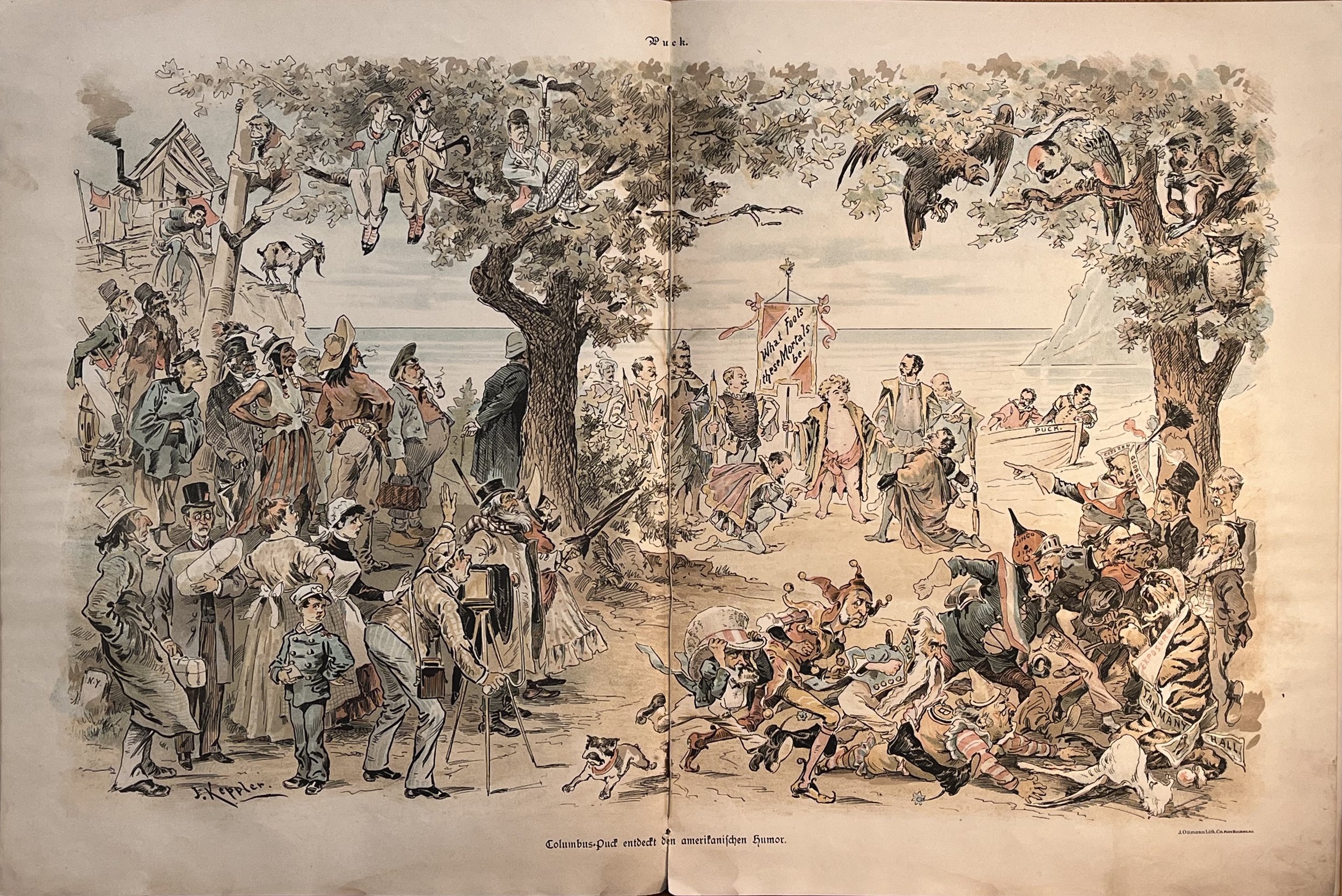

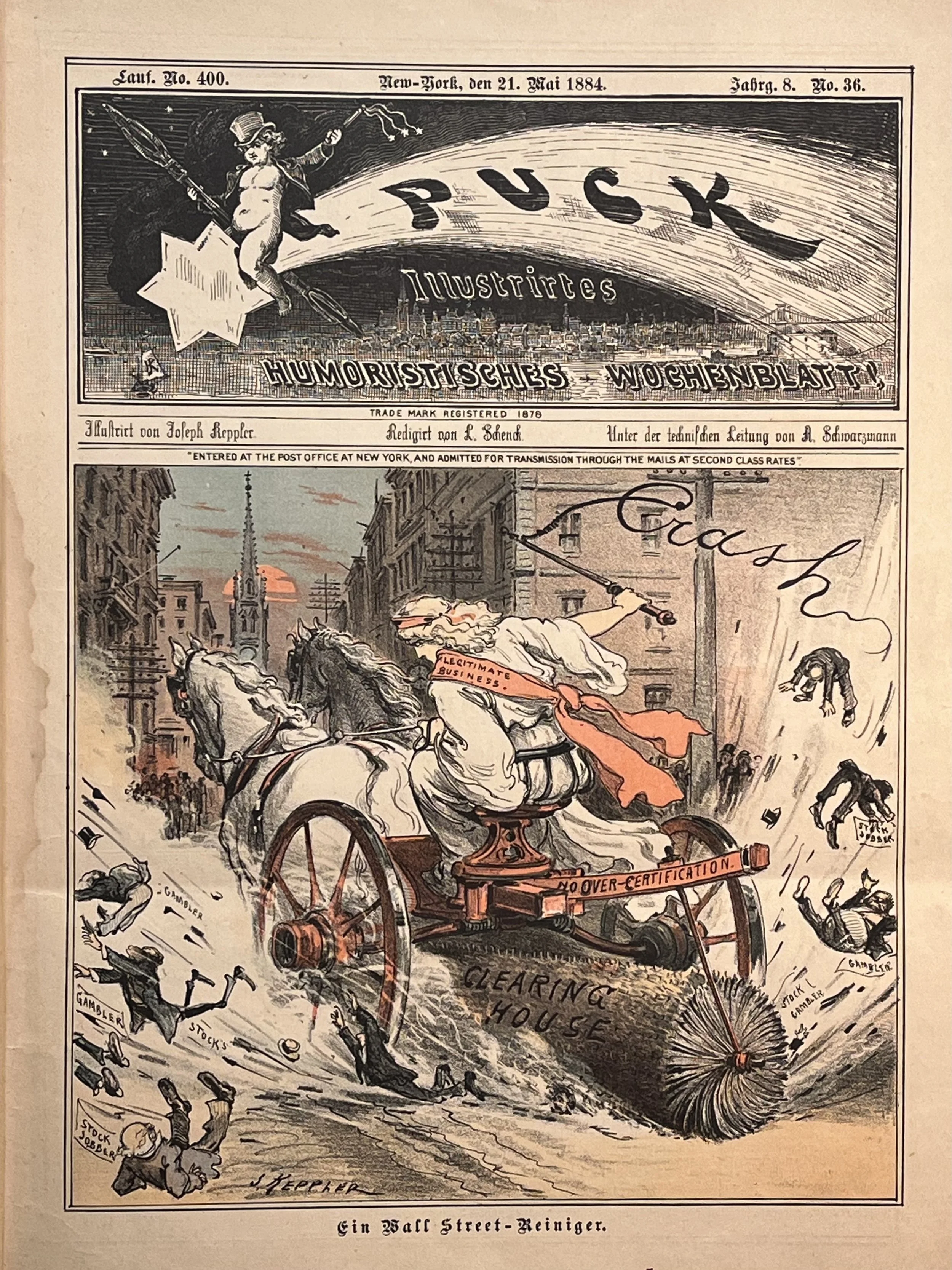

Keppler’s importance lies not only in his drawings but in the institutions he built. After several short-lived German-language satirical weeklies, he founded Puck in 1871, first in St. Louis and later in New York. By 1877, Puck appeared in both German and English editions and quickly became one of the most influential illustrated magazines in the United States. Its use of large-format, color lithographic cartoons transformed political satire into a mass visual language, displayed prominently on newsstands and read well beyond elite audiences.

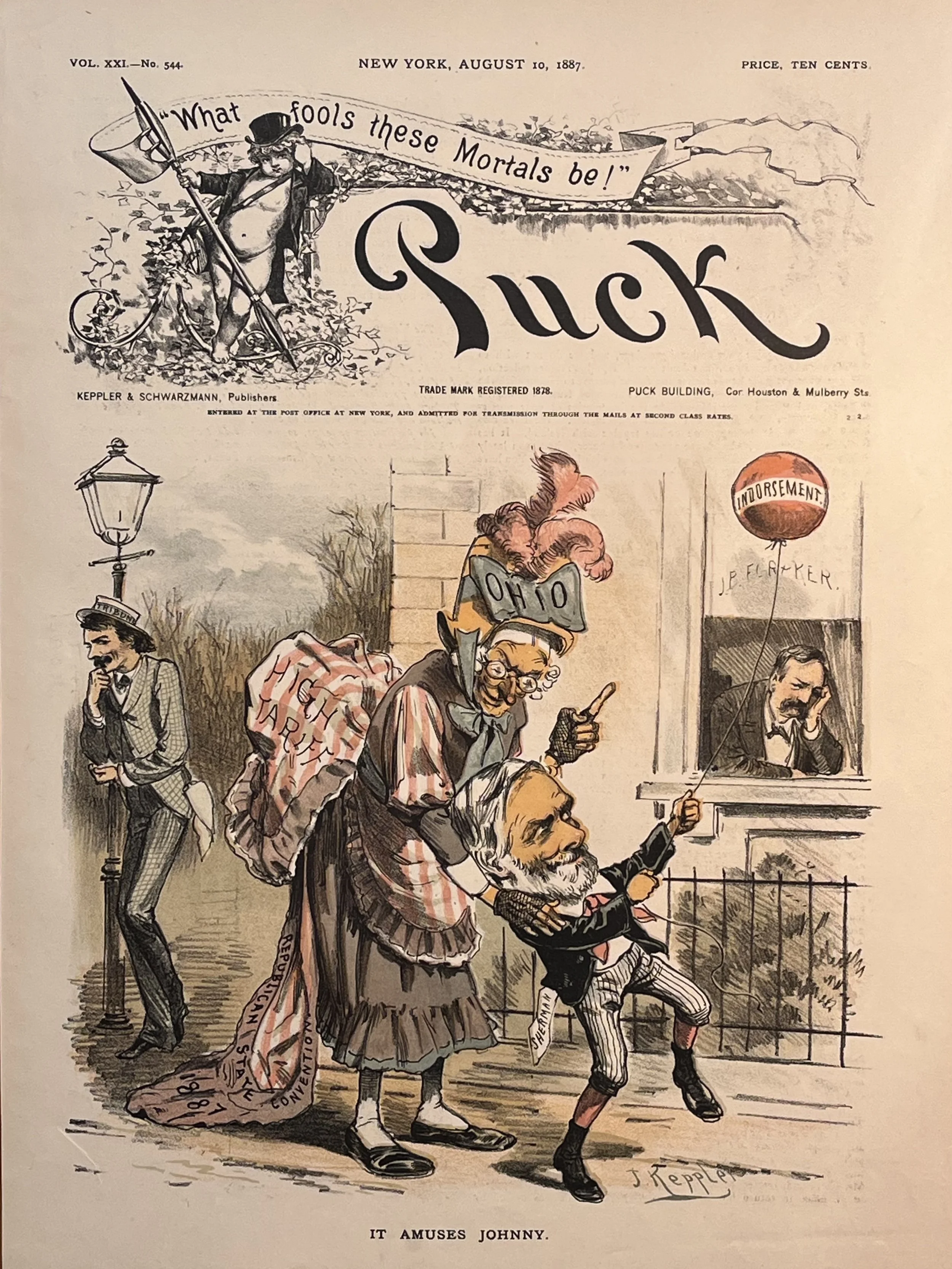

As editor, artist, and organizer, Keppler created a platform that shaped American cartooning for decades. Puck launched or sustained the careers of many major illustrators and writers, while Keppler himself developed a distinctive style: sprawling tableaux crowded with figures, symbols, and visual arguments rather than single-punchline jokes. By the 1880s, Puck had become a central interpreter of American political life. Keppler’s health declined after the strain of producing special editions tied to the 1893 World’s Fair, and he died in New York in 1894. His son, Udo Keppler, continued the magazine, extending its influence into the twentieth century.

Political Focus

Keppler’s cartoons were fundamentally concerned with power—how it is accumulated, disguised, and protected. His most enduring works attack political corruption, corporate monopoly, and the capture of democratic institutions by wealth. Nowhere is this clearer than in The Bosses of the Senate (1889), which depicts industrial magnates looming grotesquely over a diminished legislature while the “People’s Entrance” remains locked. Images like this helped fix anti-oligarchic critique in the American visual imagination and remain among the most widely reproduced political cartoons of the nineteenth century.

Unlike contemporaries who relied on singular mascots or moral allegory, Keppler favored systemic satire. He visualized politics as machinery, theater, and crowd behavior—complex structures sustained by collusion rather than individual villainy. His work repeatedly returned to themes of graft, patronage, and spectacle, particularly during presidential elections, when Puck functioned as a blunt counterweight to official narratives.

At the same time, Keppler’s politics reflect the contradictions of his era. While fiercely critical of monopoly power and elite corruption, Puck under his direction also reproduced exclusionary views, including racist caricatures, opposition to women’s suffrage, and nativist sentiment. These tensions are not incidental; they reveal how structural critique and social prejudice coexisted within nineteenth-century reform culture. Keppler’s legacy, preserved today in major museum and archival collections, lies not in moral purity but in the lasting force of his visual arguments—images that taught a mass public how to see power, even as they remained shaped by the limits of their time.